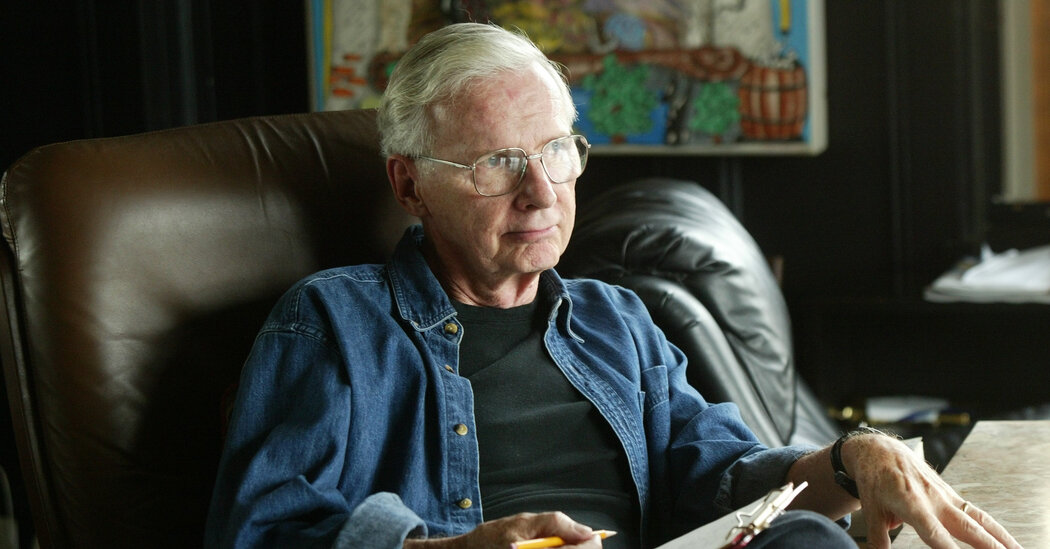

Thomas J. McCormack, an iconoclastic chief executive and editor who transformed St. Martin’s Press into a publishing behemoth with best-selling books like “The Silence of the Lambs” and “All Creatures Great and Small” and its own mass-market paperback division, died on Monday at his home in Manhattan. He was 92.

The cause was heart failure, his daughter, Jessie McCormack, said.

The few props that Mr. McCormack employed from the 18th floor of the Flatiron Building in Manhattan — an ancient adding machine, his cigar and the daily tuna sandwich that substituted for the typically well-lubricated publishers’ lunch — belied a rare fusion of marketing savvy, which enabled him to buy future best-sellers, and editorial scrupulousness, which led him to make good books even better.

During his tenure as chairman, chief executive and editor in chief of St. Martin’s, Publishers Weekly called him “one of the great contrarians of publishing, who believed, against the publishing grain, in volume at all costs.”

Mr. McCormack, the magazine said, had turned St. Martin’s “from an insignificant trade house on the brink of bankruptcy to a quarter-billion-dollar powerhouse with one of the most extensive lists in the business.”

In book publishing, where executives have customarily shied from innovation, Sally Richardson, publisher-at-large of Macmillan, St. Martin’s parent company, said of Mr. McCormack in 1997: “He was never afraid to zig when the industry zagged.”

Mr. McCormack put it this way, in reflecting to The New York Times in 2002 on a theatrical script that he wrote about the book business: “You have to make hard decisions you know are going to hurt. As the publisher in the play says, ‘Reluctance may have its attractions, but you don’t want it in war or in business.’”

He published more fiction than any other house, and the mass-market paperback division he launched in the late 1980s was the first by a hardcover publisher since Simon and Schuster established Pocket Books in 1939.

He became chief executive of St. Martin’s in 1970 and went on to publish immensely popular books like “All Creatures Great and Small” (1972), James Herriot’s account of his life as a Yorkshire veterinarian; “The Far Pavilions” (1978), by M.M. Kaye, about the British Raj in India; and “The Silence of the Lambs” (1988), Thomas Harris’s harrowing tale of a cannibalistic serial killer.

Not every book was a hit. In 1996, St. Martin’s halted publication of the biography “Goebbels: Mastermind of the Third Reich,” by David Irving, a Holocaust-denier, after concluding that it was “inescapably anti-Semitic.”

One book that Mr. McCormack wrote himself, “The Fiction Editor, the Novel, and the Novelist: A Book for Writers, Teachers, Publishers and Anyone Else Devoted to Fiction” (1989), pulled no punches.

“Not to be mistaken for a polite disquisition on what book editors do,” the columnist Art Seidenbaum wrote in reviewing the book in The Los Angeles Times, “Thomas McCormack is more interested in things editors do not do — having insufficient craft or cleverness to do them.

“In the course of skewering editors for sins of omission,” he added, “McCormack also punctures college English teachers for missing the point in lit crit, lambastes publishers for not overseeing the editing process and pokes at novelists when they become book reviewers.”

Thomas Joseph McCormack was born on Jan. 5, 1932, in Boston as Michael Gerard Griffin. He was renamed when he was adopted by Thomas and Lenore (Allen) McCormack. His father was a printer, and his mother oversaw the household.

After graduating from Stamford High School in Connecticut, he earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Brown University (graduating summa cum laude with a 4.0 grade point average) in 1954. He then served in the U.S. Army at the American embassy in Rome and went on to study at Harvard as a Woodrow Wilson Fellow.

In addition to his daughter, he is survived by his son, Daniel; and six-half siblings, Michael, Peter, Sean, Brigid, Sheila and Joseph Boyle, all of whom he met for the first time when he was in his mid-60s after finding them through DNA tests. His wife, Sandra Danenberg, a fiction editor, died in 2013. Another son, Jed; a sister, Ann Jackson; and another half sister, Maureen Murphy, also died earlier.

After he retired from St. Martin’s, Mr. McCormack gave Brown University more than $1 million to build the McCormack Family Theater on its campus in Providence, R.I.

Early in his career Mr. McCormack wrote newscasts for WSTC, an AM radio station in Stamford, until 1959, when he joined Doubleday and became an editor at Anchor Books and then Dolphin Books. He started Perennial Books at Harper and Row before leaving for New American Library to run Signet Classics and Mentor Books, where he published “The Double Helix” (1969), the molecular biologist James D. Watson’s account of his research team’s discovery of DNA.

In the late 1990s, after helping to negotiate the company’s sale to Holtzbrinck Publishing Group of Germany, Mr. McCormack retired from St. Martin’s to write a column for Publishers Weekly and to return to playwriting — he had written “American Roulette” in 1969 about a Black job applicant being interviewed at an unidentified company — an endeavor that he had figured, wistfully, three decades before that he could pursue part-time.

In 2002, his play “Endpapers,” about succession in the overheated executive suites of a publishing company, was produced Off Broadway. A New York Times reviewer, D.J.R. Bruckner, wrote that “Mr. McCormack’s mischievous enjoyment of his story is infectious.”

Bob Miller, the president and publisher of Flatiron Books, recalled Mr. McCormack’s “relentless urge to teach.” Mr. McCormack’s advice to fellow editors: Do no harm. Their most vital attribute: sensibility.

“Without it, the editor with a script is like an ape with an oboe,” he wrote. “You can be sure no good will come of it, and the most you can hope for is to get the oboe back intact.”

Still, recasting themselves as authors remained a risky proposition for publishing executives.

“Gone are the clouts of being omniscient, reclusive or just plain certain,” Mr. Seidenbaum wrote in his review of “The Fiction Editor.” Mr. McCormack, he continued, “enjoys various sorts of fame for his acute commercial instincts, for his love of serious literature and for his laconic personality — occasionally interrupted by wry bursts of wit and volcanic eruptions of temper.”

The review concluded: “Only passion for authors and readers could have moved him out of the director’s suite and into the sniper’s range. His courage earns applause. His advice deserves attention. And his passion should be requited; this is worth reading and heeding.”