In 2004, Steven Spielberg made an entire movie about the terror of getting stuck for months in an airport, but I might be happy never to leave the new LaGuardia

Air travel itself, the part where you are crammed like a rodent into a metal tube, is clearly miserable. So is everything in its orbit: the barfsome cab from the city, the shameful indignity of security, the sullen panic of being away from home, and—most of all—the ghastly purgatory of the airport that detains you.

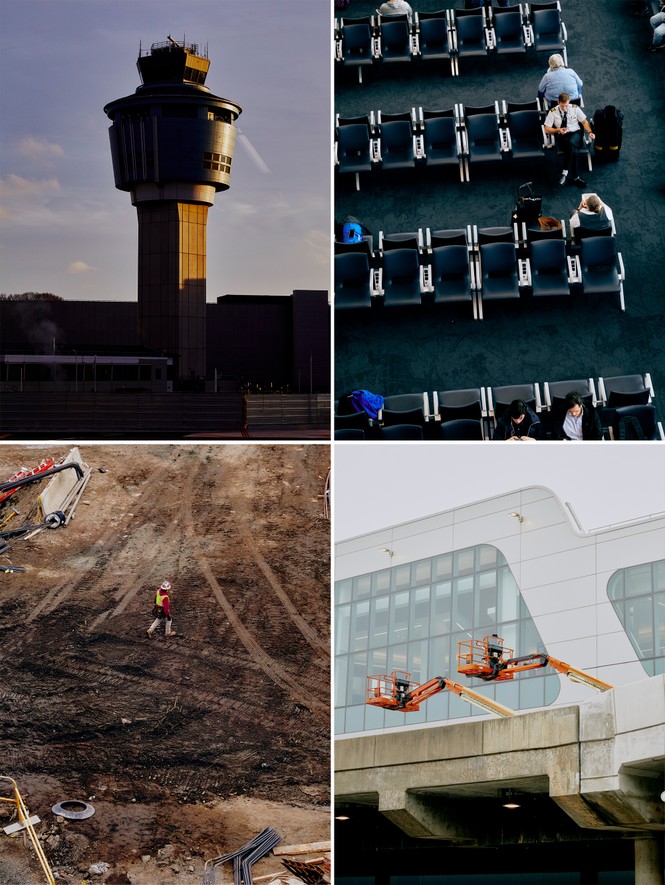

For a very long time, New York City’s LaGuardia Airport felt like the intricately dressed set of an apocalypse film. Spread across its terminals were abandoned check-in stands gone feral, floors damp with discharged moistures, low ceilings looming over dark corridors. Now, near the end of a nine-year, $8 billion rebuild of its main terminals and roadways, LaGuardia has become an unexpected hero for American infrastructural renewal. It is an incredible airport.

Terminal B, which houses most airlines, feels like a theme park—in a good way. Delta’s Terminal C, still under construction, has had its cramped and dingy concourses replaced with airy new spaces and a swank, cavernous airline club. Across the airport, sedans and taxis breeze through drop-offs and pickups unencumbered. The aircraft taxiways flow now too, making arrivals and departures more efficient. Slowly, word is getting out. People return from the Big Apple and talk about their trip to its airport instead of its restaurants or museums or theaters.

I went to LaGuardia to find out how this unlikely victory was wrested from the claws of long-term neglect—and what its example can teach a nation with decrepit and outmoded infrastructure. Many of America’s roads, bridges, airports, and other facilities to keep the people and the economy in motion were erected in the 1960s, two generations ago. In the time since then, the U.S. population has nearly doubled, yet efforts to address the nation’s growing need have fallen flat. Even 2021’s giant infrastructure bill invested only a fraction of what many civil-engineering experts say the nation needs.

Our country once took pride in building things, but then all the things got built. To take pride in rebuilding them will require new approaches to design. When I paid a visit to the renovated airport in East Elmhurst, Queens, I found that it has a message for America: The future of infrastructure is here, and it’s fun, and it’s expensive, and it’s built right on top of its forebears.

Frank Scremin, an extremely tall, impossibly friendly mechanical engineer turned airport-management CEO, rushed me up an escalator. (Shocked that I’d met a friendly person in New York City, I quickly learned that, of course, he’s also Canadian.) I’d just traversed the largest TSA checkpoint I’ve ever seen in a matter of minutes. It was an unusual experience in that it did not create in me feelings of existential despair. A curtain of windows dumped natural light across my path as I tried to get my bearings. “We have to go,” Scremin said. “The show is about to start.”

The escalator spilled us directly onto a floor of shops and then out into a courtyard where patterned streams of water were surging from the ceiling into a fountain below. Projectors, set up above, cast images of the Statue of Liberty, the Chrysler Building, and other New York landmarks across the runnels, synchronized to music. This was “the show”—a Vegas-style water feature—and the passengers nearby stood rapt.

An airport isn’t generally a place where one stops moving, except to wait, sit, eat, or urinate. That’s even more the case in New York City, the world’s most impatient place. But in the center of the rebuilt LaGuardia, I watched, mesmerized, as travelers parked their roll-aboards abruptly, just so they could watch the stalks of water raining down. The shows change seasonally, giving even frequent fliers a reason to pause.

Airlines and their passengers have conflicting goals. An airline wants to get passengers to the gates and on the planes on time. Passengers want to avoid the boredom and discomfort that comes with spending time in airport seats. The only available distractions—walking, looking, shopping, eating, and entertainment—come at the cost of anxiety around departure.

Terminal B attempts to address this problem in its physical design. A central check-in and security space leads to this commercial zone, which then branches out to two concourses of gates, each accessed via a glass sky bridge that rises over the taxiways, planes passing underneath. Large, continuously updated signage shows travelers the timing of their flights. Human agents flank these signs, ready to answer questions and give advice.

“In the U.S., we’re very much a go-to-the-gate culture,” said Scremin, who led this terminal’s redevelopment and now heads its management for LaGuardia Gateway Partners, a private-sector operator. By encouraging people to occupy the commercial district that radiates out from the fountain for as long as possible, Scremin explains, the airport discourages them from crowding together too early at the gates. It also brings in revenue for Scremin’s company, through retail leases.

Both goals are best accomplished, it turns out, by filling the airport with gratifying, even meaningful, activity. Scremin sees his role as being more like a hotelier’s than a property manager’s. Lighting dims and cools as the day turns to evening. The staff are dressed in black, hotel-style uniforms, and even the restrooms have attendants—and shelves, and entryways wide enough that you don’t bump suitcases with other passengers. The terminal is a place you want to be in rather than one you wish would just spit you out again. This is LaGuardia’s first lesson for rebuilders. Infrastructure can’t just serve a functional purpose, not anymore. It has to offer an experience.

Some might sneer at that experience—Ugh, the airport has been Disney-fied. But let’s be honest: So has everything else. Times Square is a cartoon circus, and SoHo is a shopping mall. Little is packed in the Meatpacking District, and Washington Square Arch is an Instagram backdrop as much as a monument. Consumerism is crass, but it can be a price worth paying for renewal.

LaGuardia, which opened in 1939, was long overdue for some improvement. By the ’60s, and the heyday of the jet age, the city had already outgrown it. Half a century later, the airport felt more punishment than port. The terminals, far too small and pressed too close together, created a bottleneck for runway traffic that added to delays. Funnels routed roof leaks into trash cans scattered around the terminals. On the streets outside, cars clogged departure lanes, and taxi-stand queues overflowed with deflated travelers. LaGuardia was a hellscape that even demons had abandoned.

In 2014, then–Vice President Joe Biden inveighed against the place: “If I took you and blindfolded you and took you to LaGuardia Airport in New York, you must think, ‘I must be in some third-world country,’” he said at an event in Philadelphia, adding “I’m not joking” when his audience laughed. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which is responsible for the facility, had been talking about redevelopment for years, but Biden’s comment was a catalyst. Until then, Port Authority Executive Director Rick Cotton told me, redevelopment at LaGuardia had been done piecemeal: a new garage here, a renovated road there. But this time the agency developed a master plan to redevelop the whole airport—its two main terminals and the entire roadway network.

“As if rebuilding an airport isn’t challenging enough,” Cotton said, “the commitment was to keep it operating during the construction.” LaGuardia was serving about 28 million passengers a year at the time, on more than 350,000 flights. All of those people and flights were meant to continue as before, except the old airport would slowly vanish as a new one took its place.

The charge, both crackbrained and essential, reveals LaGuardia’s second lesson: rebuilding infrastructure means erecting new on top of old. A roadway or a power plant or an airport that nobody needs and isn’t used doesn’t have to be fixed up. Infrastructure gets rebuilt because it’s still important, and that’s what makes rebuilding hard.

To solve this problem, the Port Authority collaborated with Terminal B’s LaGuardia Gateway Partners and Delta Airlines, which operates Terminal C, on a design that would allow them to construct the new airport terminals over the old ones, as in physically above them. The constraint to keep the airport fully operational got baked into the new design. At Terminal B, the dramatic sky bridges that ferry passengers from the commercial center to the concourses were put there not for drama, but to allow the builders to keep the old airport operating beneath the bridges while the new one was constructed (after which the old terminals were demolished and turned into taxiways).

In the terminal, Ryan Marzullo, Delta’s managing director of New York construction and design, showed me the traces of such decision making in the completed structure, including angled steel pylons in passageways that had to be overbuilt with structural trusses to accommodate the old roads, where taxi and passenger-car traffic flowed underneath. Suspending the bridge temporarily, he said, cost at least $8 million. Marzullo had many other stories of costly construction carried out just to make way for more, even costlier construction. Twenty million dollars went into a temporary elevated road that was used for two years during construction and eventually demolished.

These are design and engineering feats, but also testaments to will, collaboration, and the acceptance of a budgetary reality that hasn’t been commonplace for a century: Sometimes you just have to spend money—a lot of money—to get something done. Rick Cotton admits that wouldn’t have happened without the Port Authority’s private partners. LaGuardia’s failure, so far, to extend subway service to its door shows just how difficult fitting the pieces together is. (It might yet happen.) But the lack of public transit is to some extent a function of what was there before: That’s what happens when you’re building new on top of old. The refurbished airport is more efficient than it’s ever been, but the ghosts of its deficiencies linger.

Airports, wrote the anthropologist Marc Augé in the early 1990s, are “non-places.” Like hotels, conference centers, and shopping malls, they could be distinguished precisely by their indistinctness. When you go inside most airports, Augé explained, you might as well be going anywhere—New York, Topeka, Paris, Macau.

The new LaGuardia aspires to be not just any airport, but New York City’s airport. The fountain show in Terminal B offers place-ness; so do local-business outlet shops, installations by local artists, and expansive views of the Manhattan skyline. Indeed it was the lack of this quality—or at least an embarrassing mismatch of place—that inspired the first version of the airport, back in the ’30s. After landing at Newark, the only commercial option at the time, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia complained that his ticket said “New York,” but he had landed in New Jersey. He demanded to be flown to the city for real, kicking off a campaign that eventually led to the new development. (As mayor, La Guardia was an infrastructure guy, overseeing the construction of two city airports, including the one that would later take his name.)

Shame and pride are two sides of the same coin. Twice now, the dishonor of New York City’s airports has helped catalyze their future. So here’s the third and final lesson for reinvigorating the nation’s infrastructure: Americans pretend that reason drives big changes, but passion always takes the wheel. Even Cotton, of the Port Authority, seems to think that’s true. When I asked him what other municipalities might learn from LaGuardia, he first listed off some platitudes about ambition and capability, a commitment to overcome obstacles and go through walls. But then he acknowledged another, deeper motivation: “the dismal situation to which we had fallen.”

Perhaps the inspiration for renewal can benefit from, or even require, an awakening humiliation. LaGuardia’s reconstruction was, in some sense, a response to Biden’s insult, but also to the disgraceful state of the airport—which has now been transformed into a swanky theme park. Rebuilding wasn’t easy, but the challenge of deciding to rebuild came first. Perhaps the pride of building is less important than the shame of having failed to do so. If the nation’s civil engineering has now become a joke, and “infrastructure week” is just a punch line, that could mean America is on the right track.