I spent the end of May and the beginning of June in the West Bank and occupied East Jerusalem, first as a guest of the Palestine Festival of Literature, and then documenting daily life in my sketchbook. It had been eight years since my last trip to Palestine, and on the face of it, everything had gotten worse. The contradictions that plague any ethnonationalist project had all come to a bloody head with the reelection of Netanyahu last fall and his appointment of openly fascist ministers Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich, who have been encouraging settler rampages across the West Bank. Yet in some ways the oppression is just more obvious now. The checkpoints still resemble cages. The bombs still fall on Gaza. The West Bank Wall, that monument to cowardice erected after the second intifada, still defaces the land. The grind of petty state aggression—of permit denials, intrusive searches, and arbitrary rules—still provides the backdrop for outbreaks of spectacular violence by Jewish settler organizations and the military, which often work in concert. On Monday, the Israeli Defense Forces launched a full scale invasion of the Jenin refugee camp in the West Bank with airstrikes, drones, and armored bulldozers, killing at least twelve Palestinians, injuring a hundreds, and forcing three thousand people from their homes.

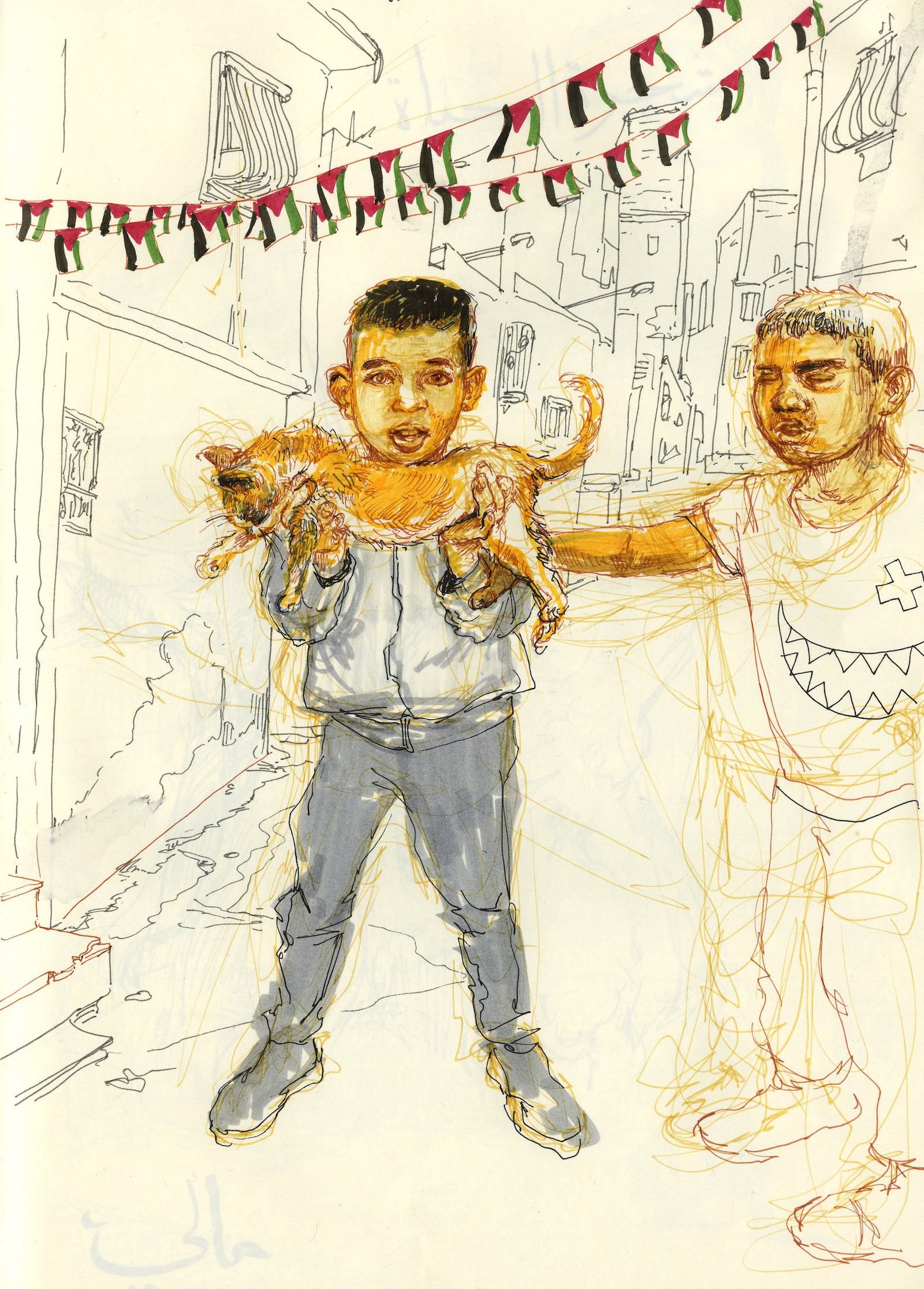

“We have on this land all of that which makes life worth living,” wrote Mahmoud Darwish, Palestine’s national poet. The land remains, its terraced hills trashed with plastic bottles and softened with wild za’atar, its stone walls, its swaggering hustlers, its wry old ladies exhausted and indomitable, their glittering laughter, their generosity and contempt. What else makes life worth living, according to Darwish? The conqueror’s fear of memory. The tyrant’s fear of song.

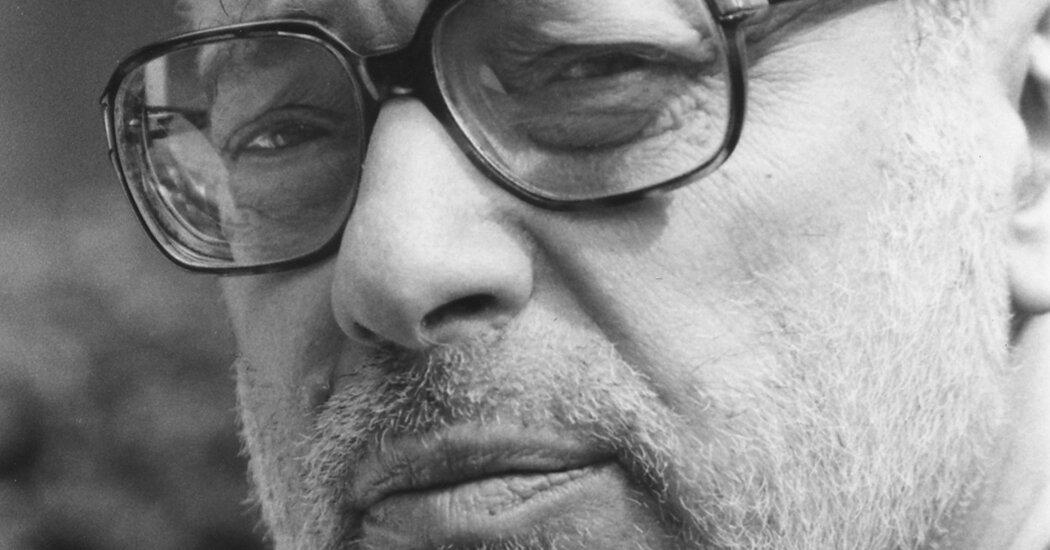

My friend Mariam Barghouti is a journalist based in Ramallah. I stayed in her spare bedroom for a week. Mariam is never on time, because she stops to talk to everyone on the street, an essential quality of a good journalist. She picks the jasmine that grows everywhere in springtime and propagates it in bottles on her windowsills. When she does interviews after this or that IDF atrocity, she brings bubbles to keep the kids happy. She feeds her friends with compulsive generosity—cherries, cigarettes, take-out schnitzel—and shoots candid videos that show them at their best. One morning she made coffee for my bleary self. She stirred the grounds in the ibrik. The light hit her long neck. With her hair piled into a topknot, she resembled one of Degas’s ballerinas. Drawing does little, I sometimes feel, but it can capture moments of grace.

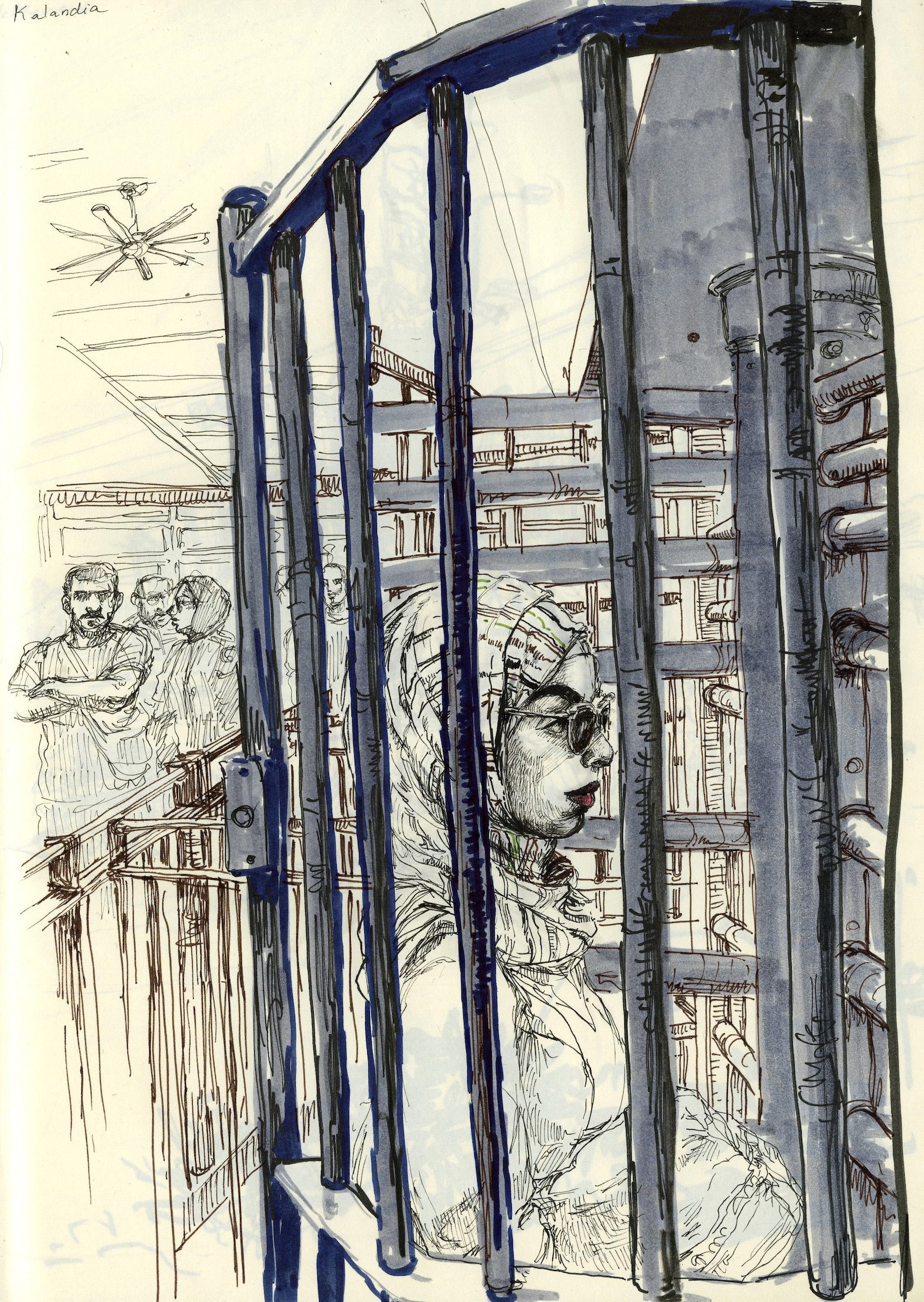

One way for Palestinians to get into Jerusalem from Ramallah is through Qalandia checkpoint, and this was the route I usually took. Resembling a cross between a slaughterhouse chute and the worst subway station in New York, Qalandia is a series of cages and turnstiles manned by teenage Israeli conscripts—often Ethiopian and Arab Jewish girls, in keeping with the unofficial racial hierarchies of the Israeli army—whose job is to push the button that turns the turnstile. While Palestinians wait, these soldiers ignore the button and instead snap selfies and mess around on TikTok. How much life is wasted trapped in a turnstile while these heavily armed kids scroll away on their smartphones?

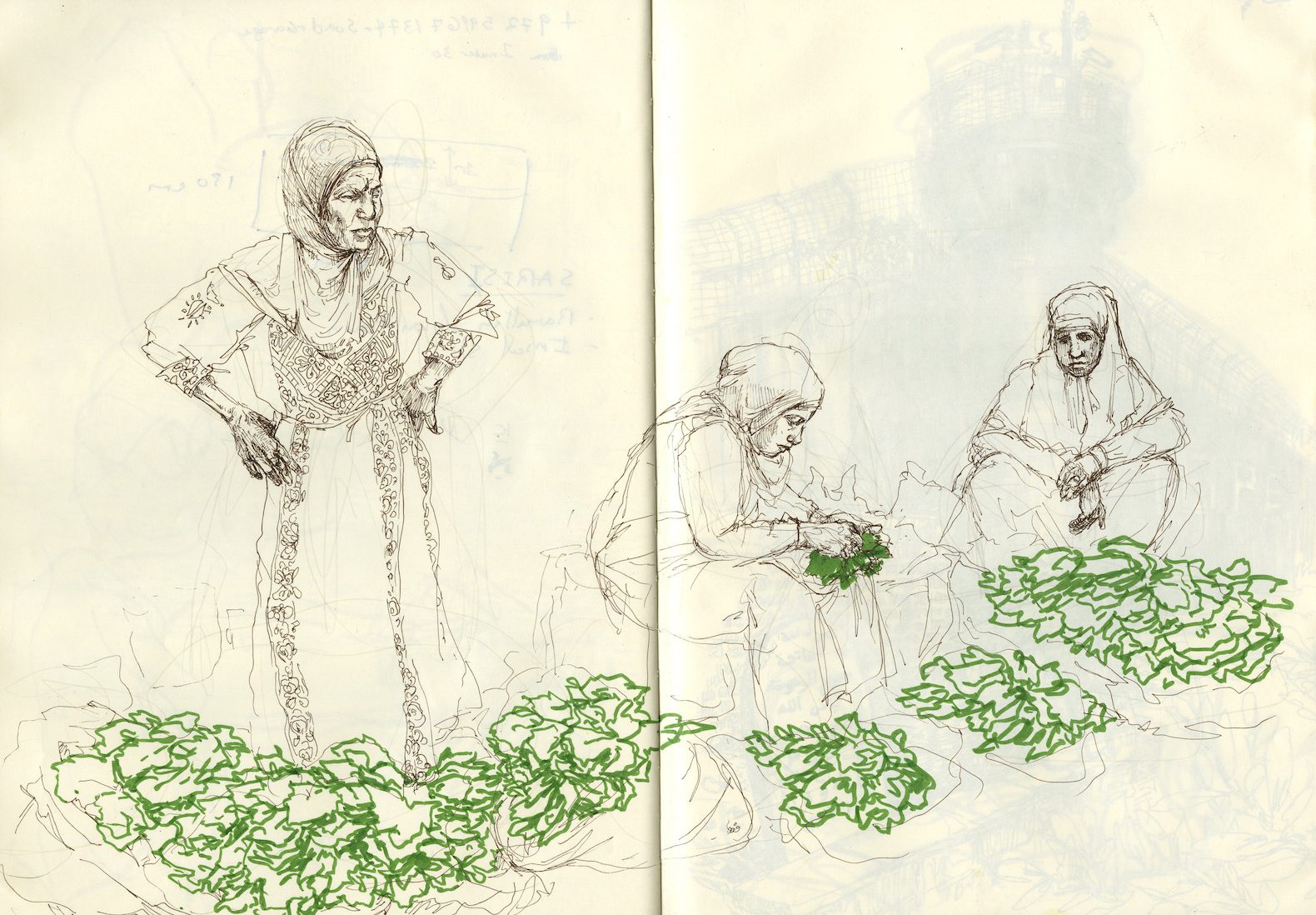

Tough farm women, elderly enough to be allowed to pass through the Israeli checkpoints into occupied East Jerusalem, arrive early in the morning to stake out their share of pavement on Salah al-din Street, in one of the souks in the Muslim Quarter, or in the honey gold shadow of the Damascus Gate. They come from the West Bank with bales of produce, spreading piles of grape leaves, mint, sour green plums, all so fresh you can taste them with a glance. They do brisk business. The women are not liked by the city authorities, who detest this sort of unlicensed commerce when done by Palestinians. One morning I saw a group of men in the matching T-shirts of the municipality roll up to one of the women and make off with two crates of grapes while she wept with helplessness and rage.

Half a million settlers live in the West Bank in defiance of the Geneva Convention and of international law, an act that Michael Lynk, the UN’s special rapporteur for human rights in the Palestinian territories, calls a war crime. While past Israeli governments sometimes feigned disapproval of the settlements, they still maintained their segregated roads and supplied them with water, power, and military protection. Now the Netanyahu government champions settlements as its top priority—even as settlers torch homes and attack Palestinians in pogroms across the West Bank. Seen from a bus window, hilltop settlements have a distinctive cookie-cutter look, resembling Mediterranean Levittowns. A checkpoint bristling with cameras often sits out front.

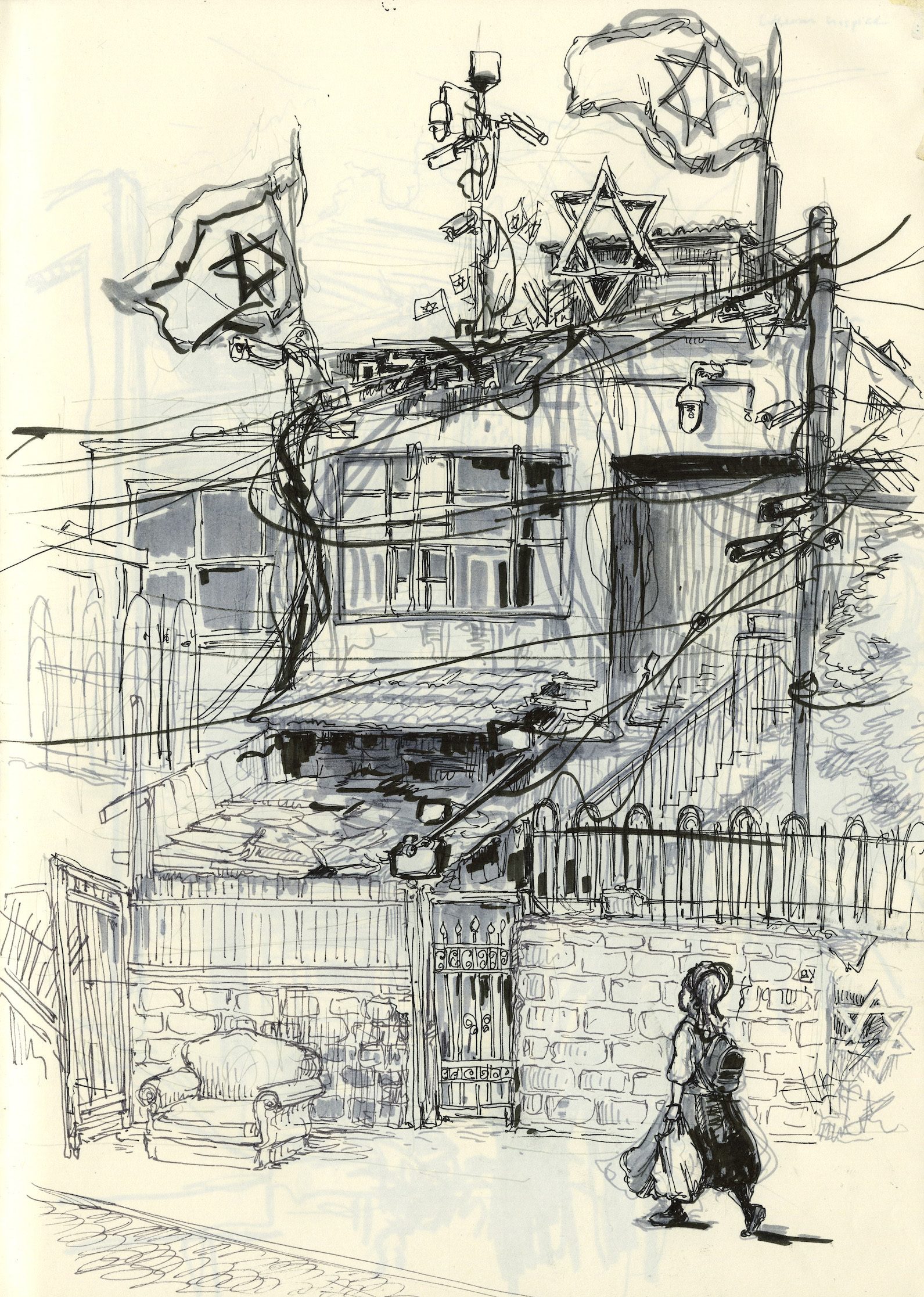

The Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood in occupied East Jerusalem made American headlines in 2021 due in large part to the social media skills of the charismatic el-Kurd siblings, Mohammed and Muna, whose family home was being squatted in by a Long Island-born settler named Yaakov Fauci (“If I don’t steal it, someone else will,” he said in one filmed confrontation that went viral). But settler groups have been targeting the neighborhood since the 1970s, working hand in glove with a ludicrous Israeli court system rigged in their favor, in both official and unofficial ways. One law allows Jewish groups to take over properties that were owned by Jews before 1948; Palestinians expelled during the Nakba have no such recourse. There is also the matter of the settler groups’ ownership documents, which Sheikh Jarrah families argue are fabricated, and which the court accepts without authentication while refusing to give Palestinians’ ownership documents any weight, whether they were issued by the UN, Ottoman records, or the Jordanian government. “If your enemy’s the judge, to whom do you complain?” Mohammed el-Kurd remarked.

Across the street from the el-Kurd home sits what used to be the home of the Ghawi family, until one night in 2009 when settlers, with the help of the Israeli police, busted in and threw all the furniture onto the street. The Ghawis have staged regular protests outside their home ever since. According to Sheikh Jarrah residents, settlers live in the Ghawi and other homes in rotations, during their stays throwing rocks and garbage, writing racist graffiti, and attacking Palestinian residents. Many of these settler organizations are funded by tax-exempt American charities such as the Central Fund of Israel, based in New York.

In 1947 Jaffa was an Arab city, an elegant port famous for its oranges, soap factories, and publishing houses. On April 25, 1948, Zionist paramilitaries began to bombard the city. The constant mortar fire, truck bombs, and a siege imposed by the Haganah, precursor to the IDF, forced nearly all of its 120,000 Palestinian residents to flee. After the city fell, the Haganah herded the four thousand who remained into a sealed ghetto in the seafront neighborhood of Ajami. The property of Jaffa Palestinians became the property of the new Israeli state. Their graceful homes—coveted for their Arab architecture despite the fact that “Arab work” is racist slang for bad construction—are now Israeli-owned hotels and restaurants. In summer the streets are filled with the thump thump thump of club music, as the young Israelis dance, oblivious, like most winners, to history.

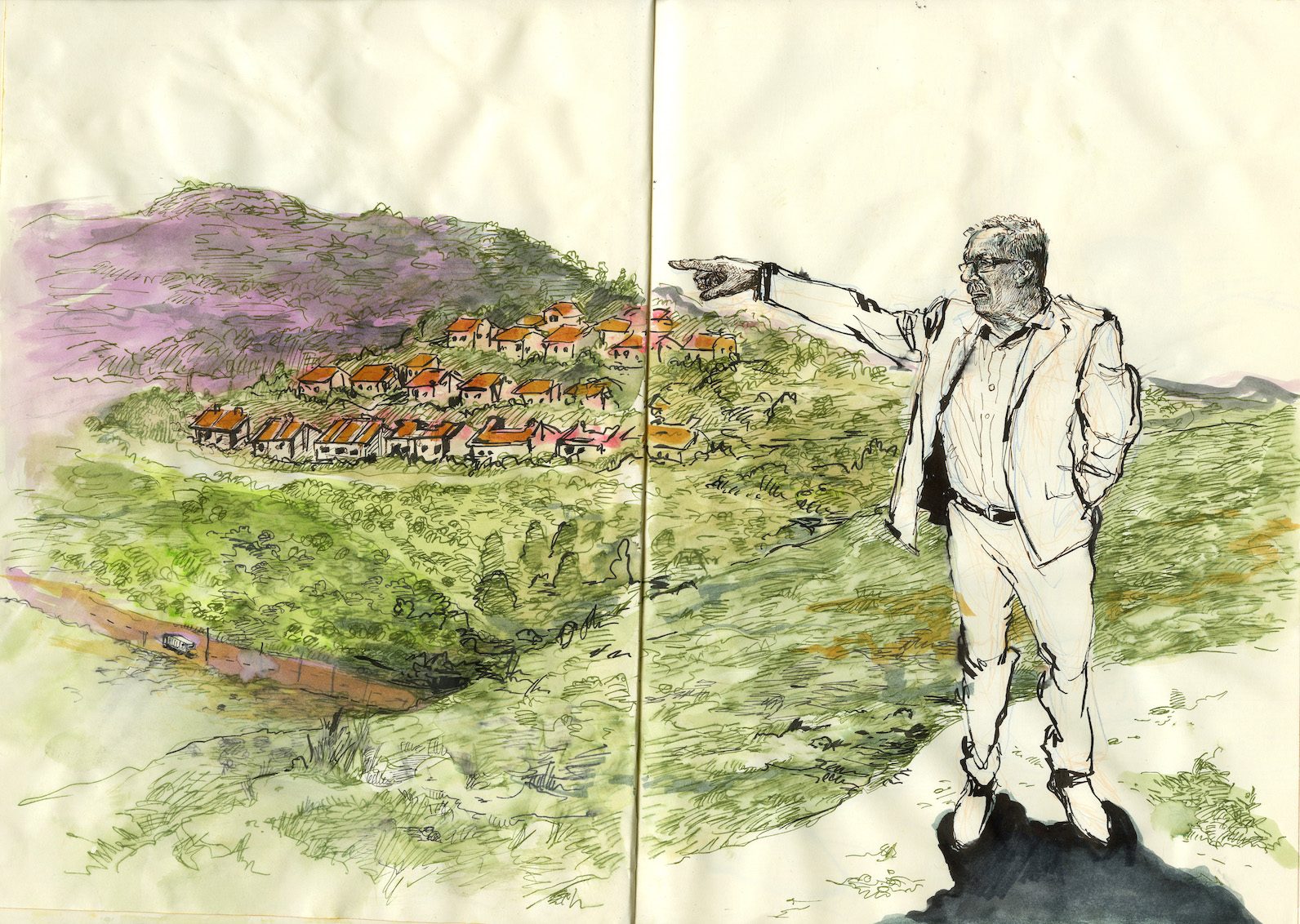

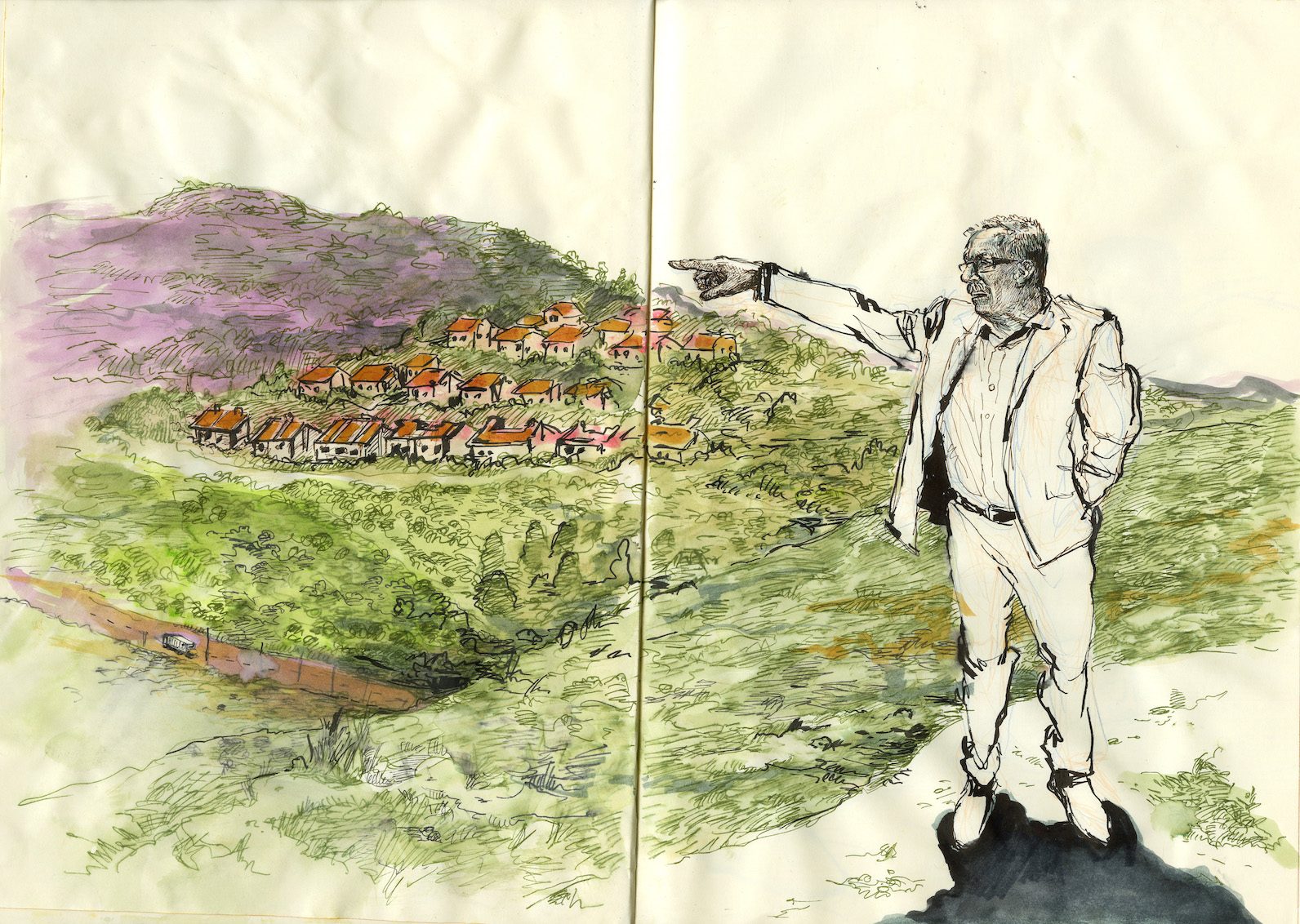

“They take all the water,” Bassem Tamimi told our group of writers with the Palestine Festival of Literature, as he stood on hillside near his home in the village of Nabih Saleh and pointed at the nearby illegal settlement of Halamish. The difference was clear: Halamish was surrounded by verdant greenery, in contrast to Nabih Saleh’s scrubby land. The Tamimi family has led protests against the settlement since 2009. In 2017 Tamimi’s teenage daughter, Ahed, became a global icon when she slapped an IDF soldier who had invaded her home, shortly after soldiers from his unit shot her fifteen-year-old cousin in the head with rubber bullets. Ahed spent eight months in an Israeli prison. As Tamimi pointed to the settlement across the valley and spoke about the duty of resistance, I thought about how many times he had likely stood on that rock and explained the violence and land theft for foreign guests, and how it all continued anyway. About a week after our visit, IDF soldiers in Nabih Saleh shot up the car of Bassem’s nephew by marriage, Haitham Tamimi, wounding him and killing his two-year-old son, Mohammed. He was the twenty-first Palestinian child that the IDF killed this year.

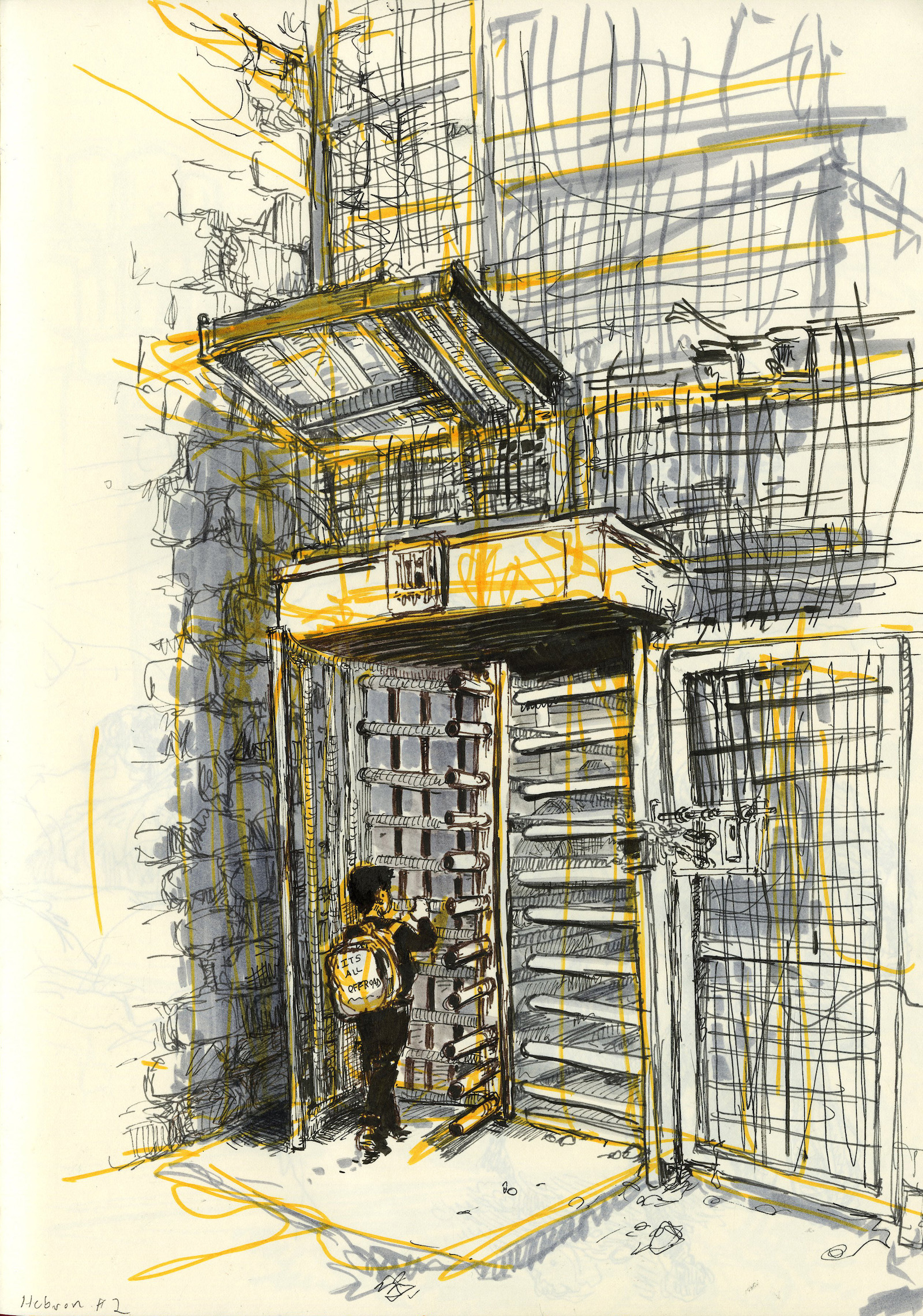

Shuhada Street used to be a lively commercial thoroughfare in the Old City of Hebron. Now it is deserted and choked by checkpoints. After Brooklyn-born settler Baruch Goldstein gunned down twenty-nine worshippers in the Ibrahimi Mosque in 1994, mass protests erupted across the West Bank, and the Israeli government responded by welding shut Shuhada’s Palestinian shops and apartment doors. The government closed the street to Palestinians after the Second Intifada, so that the few Palestinian families who still live there must enter their homes through the rooftops. This is done in the name of protecting a few hundred particularly fanatical and violent settlers who have commandeered homes in the Old City. At the checkpoint I drew, the IDF has installed an AI-controlled gun that shoots stun grenades and tear gas.

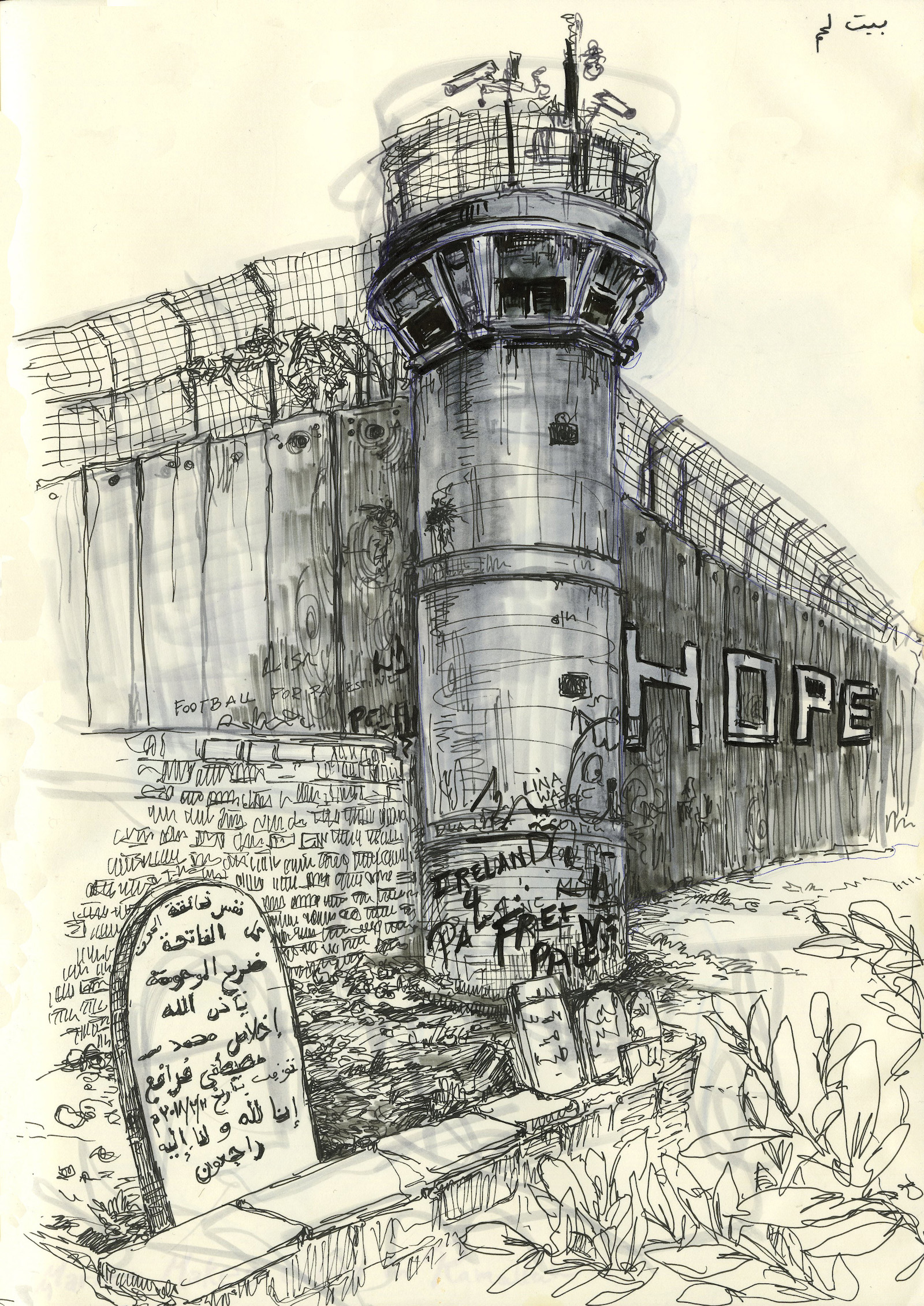

A gray cement slab, up to thirty feet high, snakes through the length of Israel-Palestine. The West Bank Wall will be 450 miles when it is completed. It deviates wildly from the Green Line, with 85 percent of it built in Palestinian territory, the better to gobble up farmland and annex illegal settlements. In the Aida Refugee Camp in Bethlehem the wall presses against a cemetery for the people of twenty-seven villages who were expelled by Zionist militias during the Nakba.

Aida Camp was founded in 1950 by UNRWA, on land leased from the Jordanian government. Like the rest of the West Bank, it fell under Israeli occupation in 1967, and the IDF destroyed most of its buildings during the Second Intifada. Palestinians rebuilt it into a warren of twisting streets, amputated by the ever-present wall. The IDF still regularly invades the camp; in 2017 the Human Rights Center at Berkeley Law found it was the most tear-gassed place in the world. Now home to over six thousand people, Aida is famous for its vibrant, fractious art scene, visible in the ubiquitous murals, the cultural centers, the circus school, and the enormous key that tops an arch near the camp’s entrance, representing the return of Palestinians to their stolen homes. What it does not have is a safe place for kids to play. The wall cut off the camp from its only green space. Now the kids play in the dust.

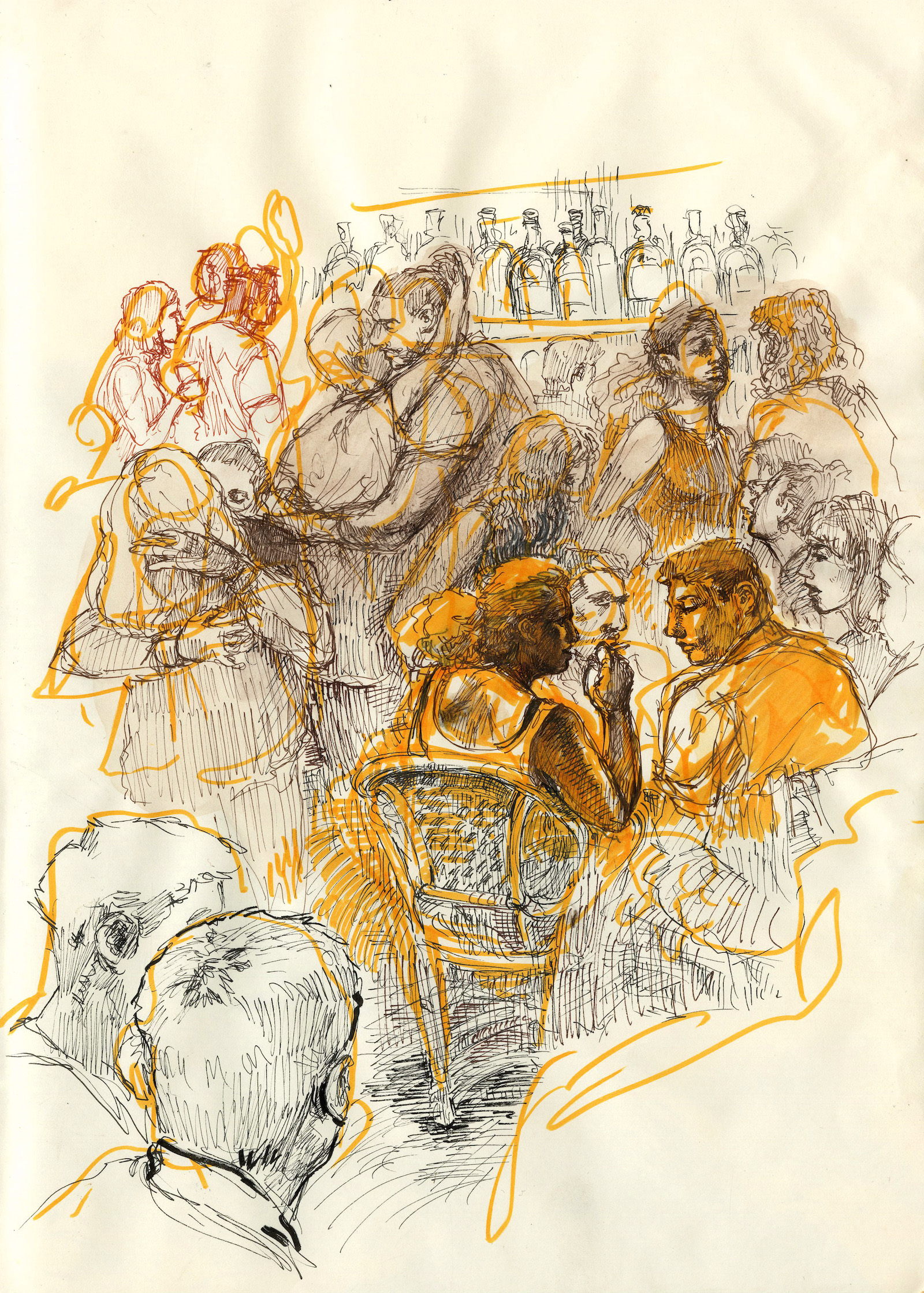

A bar in Ramallah was full of beautiful young things, cool-as-cucumber young men with perfectly styled hairdos and slate-eyed girls banging out their dissertations on laptops, cigarettes smoking away in ashtrays. When the butch girl strode in, supremely confident in her perfectly tailored shirt, she was a locus of attraction in a room that, in this sliver of land under maximal pressure, was an oasis of safety and love. I had to draw her as if she radiated light.

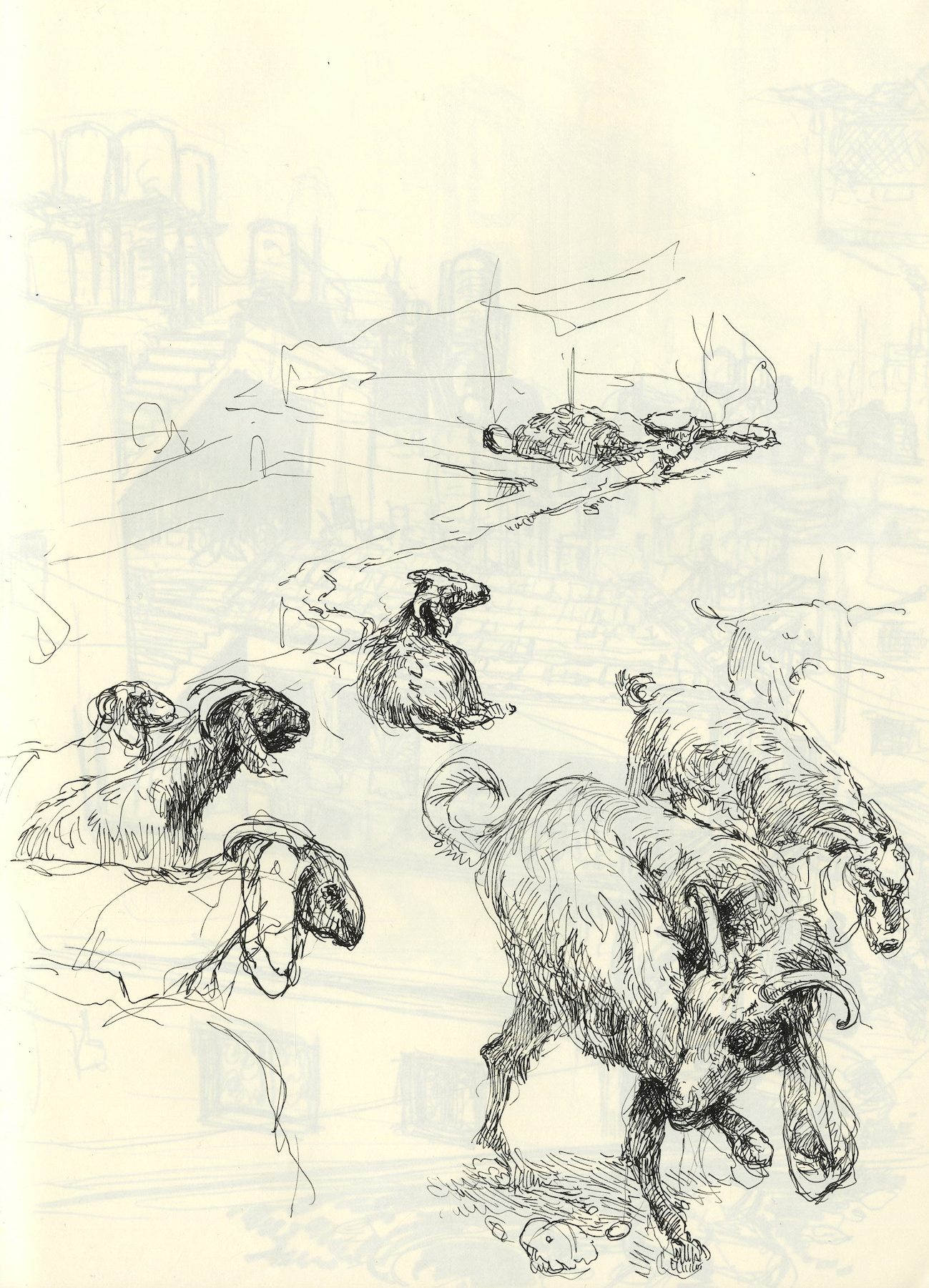

In the hills near Ramallah there is an oak tree that has stood for 2,500 years. According to the architect Sahar Qawasmi, cofounder of the nearby Sakiya cultural center, the tree has long been said to be protected by the spirit of a holy man, and Daoud Zalatimo, a prominent Palestinian artist, once built a library in its cavity. The twisted rivulets of its trunk go deep into the earth, and its leaves make a canopy to shade vast flocks of goats. It seems eternal. On other trees, there is Hebrew graffiti carved by the groups of hikers that come from settlements around the West Bank. They sometimes stomp right through the cultural center, Qawasmi said, with guns slung across their chests.

On June 8 the IDF invaded Ramallah. The city is not under Israeli control and IDF soldiers have no business there, but the Palestinian Authority did not hinder their entry. They came in a hundred military vehicles. When the young guys of the neighborhood used rocks and Molotovs to show their disapproval, the IDF shot and sprayed tear gas at them. They shot photojournalist Moumen Sumrin in the head with a rubber bullet—never mind his press vest—leaving him with a fractured skull. The IDF was there to destroy the home of Islam Faroukh, who had been arrested on accusations that he carried out bombings that killed two Israelis, one a teenager, in Jerusalem. He has not been tried and his family maintains his innocence.

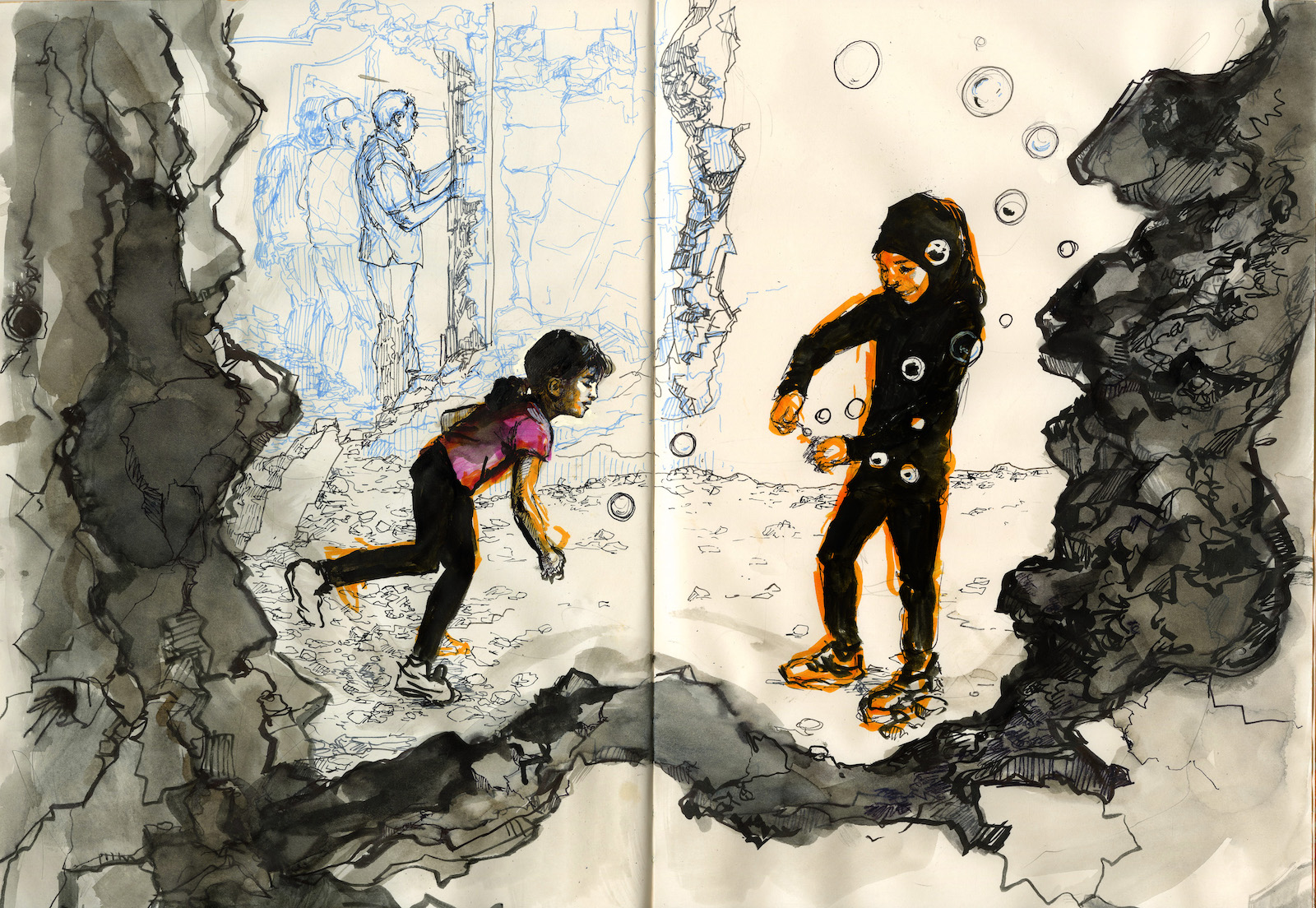

The apartment that the IDF destroyed does not belong to Faroukh but to his family, and his parents and young sisters live there. The apartments on the floors above also do not belong to him, but any damage to their structural integrity did not trouble the IDF. Mariam and I visited the day after the demolition. The entire place was an indistinguishable mess of gray rubble. Family friends were already installing metal pillars to stabilize the ceiling, and a nearby apartment was thronged with visitors. Faroukh’s little sisters played in the wreckage. They threw rocks at the scrawls that IDF had left to mark where to place explosive charges. The girls drew Palestinian flags in the dust that covered the remnants of their walls.