In 1956 Juan Goytisolo, one of Spain’s most influential contemporary writers, took a bus to the eastern part of Almería, a province in Andalusia. Under Franco, this was one of the country’s most impoverished regions, exploited by mining companies and neglected by the government. Goytisolo had come to tell the stories of the people who lived in its slums. “I remember clearly the impression of poverty and violence provoked so dramatically by Almería when I first took route 340 into the province a few years ago,” he wrote in Níjar Country, which was published in 1960 and subsequently banned, like many of his books. At the time he was living in Paris; three decades later he moved to Marrakech. He never again lived in his place of birth.

I read his book on a terrace with a view of the Alcazaba Moorish fortress one warm Saturday morning this April. I too had arrived in Almería by bus. I had come from Málaga and traveled along the southern coast, passing through lush fields and stunning scenery overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. As green valleys gave way to rocky land, especially dry this year, I could see why locals so often call Almería the “door to the desert.” Spaghetti Westerns were shot here.

As you get closer to Almería, you leave behind the olive and almond trees and enter an expanse of plastic greenhouses. According to governmental data, Almería yields about 54 percent of Andalusia’s fruit and vegetable exports—chiefly tomatoes, cucumbers, and peppers—amounting to €3.7 billion in sales last year. They boost the country’s economy and allow Europeans to eat fresh salads year-round. Satellite images show a sea of plastic that extends from the foot of the mountains to the shores of the sea.

Níjar is a small, sleepy town perched on a green hill by the Huebro Valley, overlooking the farm country. On a breezy weekend, tourists walked along the quiet streets, visiting the Memory of Water Museum—a showcase of the centuries-long struggle to find and preserve water in this region—and eating ice cream at a helateria on the town’s main square. When Goytisolo wrote Níjar Country, Almería had yet to be known for its national parks and beaches, some of the most beautiful in Spain. (Tourism has grown in recent decades, although the region sees many fewer visitors than the Costa del Sol to the west.) Instead the book evokes “settlements of a dozen isolated hovels” where Goytisolo saw families living in extreme poverty, hoping to leave this dry, overexploited land for places of greater opportunity.

In the 1950s and 1960s the state implemented the Plan General de Colonización—plan of settlement—to attract people from neighboring areas.1 It gave families land and, with the promise of industrial agriculture, the prospect of profit. Many farms in the region are still owned by the descendants of these settlers. The first landowners worked the fields themselves, but by the 1980s and 1990s farms were seeking foreign laborers to produce on a larger scale.

Migration to the region has been increasing ever since. African workers first arrived in El Ejido, a town on the other side of Almería. As intensive farming grew exponentially, the region transformed. Today shantytowns adjacent to the fields house thousands of migrants from North and West Africa, most of them undocumented. They provide cheap labor for the companies, small and large, that sustain the region’s economy and generate a huge portion of the country’s economic growth. Agriculture’s share of Spain’s GDP is one of the highest in Western Europe.

According to a recent report by the Jesuit Migrant Service, which provides Spanish lessons and legal support to undocumented migrants, greenhouses cover 32,827 hectares of the land in the province of Almería. They produce more than 3.5 million tons of fruit and vegetables, about 75 to 80 percent of which are exported. While it’s hard to find reliable data, the report estimates that 69 percent of agricultural workers are foreigners, half of them Moroccan.

Most of the laborers I spoke to told me they earn four or five euros an hour, considerably less than the legal minimum wage. They work in the sweltering heat under the greenhouses’ plastic coverings. Sometimes they put in full days, but often they are only needed for a couple of hours, if at all. Workers advertise their services by painting notes on the white plastic that covers the greenhouses—blanqueo (painting the plastic white to maximize light exposure and retain heat) or montaje (assembling the structure)—along with a phone number. Farm owners have absolute power and control over hiring and firing: several labor unions and rights groups allege that they can pay workers for fewer hours than they worked, simply let them go without compensation, and avoid responsibility if they get injured. (The company Grupo Godoy, one of Níjar’s large agricultural producers, did not respond to questions about the allegations that their treatment of foreign workers violates labor laws.)

Over the last two decades, the migrant population has increased but the availability of housing has not. Workers told me that renting in the city and villages surrounding the field is nearly impossible, either because housing is too expensive or because landlords refuse to rent to them. At night they sleep in chabolas, simple dwellings made of wood, plastic, or whatever else they can find. Some use small solar panels or plug illegally into the grid and tap local water sources, but most lack electricity and running water. Blue pesticide containers are recycled into water tanks. In some of the camps I visited, people charge their phones at shops in the nearest village and walk or bike the many kilometers home carrying big bottles of water. The chabolas are unbearably hot in the summer and cold during winter. The slums can barely be seen from the main roads; it is common, however, to see workers on bikes or scooters emerging from them early in the morning or disappearing into them at the end of a workday.

Pablo Pumares directs the Center of Migration Studies at the University of Almería, where he has lived for more than thirty-five years. He estimates that the majority of workers in the region are documented but that for the most part those who live in the shantytowns aren’t. Spain, he says, cannot offer them an easier path to residency within the terms of the European Union’s restrictive migration policy. “It’s quite complicated,” he said. Most services, such as public transportation and healthcare, don’t reach Níjar’s undocumented workers, but they prefer to stay close to the greenhouses because it increases their odds of finding work each day. Even documented workers, Pumares adds, have to contend with a nationwide housing shortage: “They could afford the rent, but there is no housing available. It’s an immense problem.”

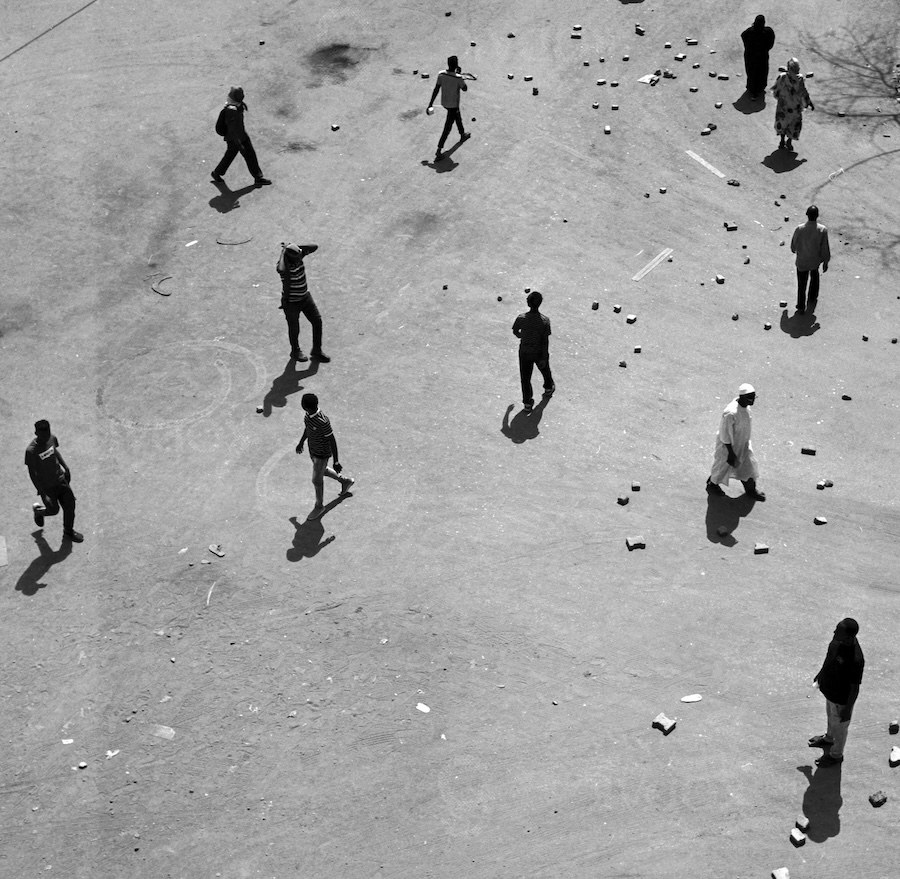

These low-paid workers dynamize the region’s economy, but many Spaniards resent their presence. In late January the Níjar City Council oversaw the destruction of a camp called El Walili, which housed hundreds of agricultural migrants. The council said they were doing so for humanitarian reasons. The former mayor of Níjar, Esperanza Pérez, defended the decision by claiming that it was the first time there was any proactive effort to address the unsanitary conditions under which so many migrants lived. Labor rights groups have speculated that the socialists then in power wanted to appeal to populist sentiment by showing that they were taking a tough line on illegal settlements. In place of the chabolas, the city provided temporary housing: 140 bunk beds inside an industrial warehouse, with outdoor showers and bathrooms. Only about fifty migrants from El Walili accepted the invitation to move in.

In April Pérez announced that the government planned to demolish all the region’s shantytowns. She insisted that the eviction would be “professional, firm,” and that they would offer new apartments to those displaced. Yet hundreds of people in the remaining shantytowns have not been approached with housing alternatives. In last month’s regional elections the socialists won ten of the city council’s twenty-one seats; ten more went to the center-right Popular Party and one to the far-right Vox. Last week Vox and the Popular Party formed an alliance to gain a majority on the council. Spain’s general elections are approaching in late July, and Vox has been gaining ground both in the region and in the country. Whoever is in power, the migrant workers in Níjar’s remaining shantytowns live in fear that their camps will be demolished next.

In Almería I found people who were tired of the media, politicians, and nongovernmental workers. They were fed up with repeating the same stories about their wretched conditions without seeing anything change. But I was there during Ramadan, and many migrants still opened their homes to me and shared their stories. The few women I met were Moroccan. They had first come to the Huelva province, in the western part of Andalusia, to work on strawberry farms.2 I met Laila, a forty-one-year-old from Beni Mellal, in the hour before she broke her fast one day in April. (Some names in this article have been changed, and many of the workers I spoke to didn’t share a last name out of fear of the Spanish authorities.) We were in Don Domingo de Arriba, a camp built on an abandoned farm near Atochares, just south of Níjar. Several people told me it was likely to be the next demolished.

Laila moved to Spain five years ago for a temporary job, but after ten days of arduous work on a farm in Almonte, she couldn’t do it anymore. More experienced women were working faster, the jefe—the boss, one of the first words workers learn in Spanish—was unkind to her, and she felt ill and couldn’t stand the heat, so she ran away with six other women. She lived for a time in the El Walili camp but left before its demolition. A fire in the unsafe dwellings destroyed everything she owned. Houseguests woke her up at 4 AM; they evacuated in their pajamas, barefoot.

Now she lives with her cousin, who had arrived eight months earlier after surviving the treacherous crossing through the waters of the Canary Islands. They share what looked like a living room and a bedroom under a large plastic tent. That day, Laila was preparing fresh juice for Iftar, the meal to break the fast after sunset during Ramadan. She told me about her three children, who live in Morocco: “Even when I make €50, I send it to my daughters,” she said. She can’t afford a trip home to visit them. “I just hope I see them again,” she said. “I could beg just to have them next to me.”

Some days earlier I had gone to see the El Walili camp, or what remained of it: a clay oven and some trash in a bare field. The camp had been around for a couple of decades. It lay on property that belongs to a few small landowners, who were not involved in the establishment of the settlement. Many told me that it had been by far the most visible migrant camp, since it was right on the road that tourists take from Níjar to San José, the main sea resort in the Cabo de Gata National Park. (Its prominence might have been one reason the authorities were so keen to get rid of it.) Witnesses reported that hours of chaos followed the legal decision to demolish the camp. People carrying their microwaves, tables, and clothes watched their homes razed to the ground. The Interior Ministry runs the police force that oversaw the dismantlement of the camp, but a spokesperson told me to talk to the Ministry of Migration, which declined to comment.

I tried to enter the warehouse where some migrants were being sheltered by the government, but I wasn’t allowed in. Two Romanian guards stood in front—Eastern Europeans often get better treatment and better jobs here—waiting for a food delivery that comes a few times a day. The migrants from El Walili were only supposed to stay fifteen days, then only two months. Some blocks away, the permanent apartments the government promised them aren’t ready yet.

In the months leading up to the destruction of the camp, the city council delivered several eviction notices; eventually a judge issued orders of expulsion. Local union activists protested, demanding that the authorities respect due process by notifying people individually or providing alternative housing before the demolition. A worker with the Union of Agricultural and Rural Workers of Andalusia (SOC-SAT), who didn’t want me to use his name or initials to avoid jeopardizing his current job search, has worked tirelessly to stop the evictions. “There are serious problems of human rights and noncompliance with labor laws and rights,” he said. “For example, when a migrant worker says he doesn’t want to work on a holiday, he loses his job.”

In February the European Coordination Via Campesina, a confederation of peasant farmers and agricultural workers, joined with eight other rights groups to issue a press release drawing attention to the destruction of El Walili and the living conditions of migrant workers in Níjar. They also highlighted the environmental impact of intensive farming, including “plastic contamination on a large scale.” The dispossession of the region’s migrant workers, they write, “is a shame for Spain, a shame for Andalucia, a shame for an agricultural system based on the exploitation of migrants.”

About a year and a half ago Father Daniel Izuzquiza, a Jesuit priest, moved to Almería to help the nationwide Jesuit Migrant Service expand its operations there. He considers it morally impossible to reconcile Spain’s lack of concern for the wellbeing of African workers with its economic reliance on their cheap labor. “They only want workers, not persons or families,” he told me. Locals seem to understand little about the ordeals workers undergo in the valley. “People do not know, do not want to know, do not really care.”

Father Daniel took me on a tour to meet with some of the people his organization helps. At a camp just outside a town called El Barranquete we met people who had moved from El Walili. Three young Moroccan men hadn’t found work that day. One of them told us that it was incredibly hard to do so without the right connections, often facilitated by shared nationality. Most arrived here on their own, and so they often find work through someone who knows a farm owner or manager well.

In Don Domingo de Arriba, on the abandoned farm, residents live in crumbling buildings or homes made out of plastic sheeting. There is a makeshift mosque, and on some days women sell clothes by one of its entrances. After fires destroyed some of the neighborhood a couple years ago, people rebuilt their chabolas with concrete, cement, and bricks. Father Daniel teaches a Spanish lesson here under a plastic tarp, writing basic words on a whiteboard: poco, mas, mucho, tan simpatico. At tan guapo (“so handsome”) the classroom fell into laughter.

Down a dirt road I met two brothers, Omar, twenty-six, and Yassine, twenty-eight. They shared one of the nicest chabolas in the camp, a one-bedroom cement home their father had bought for €1,200. It has a bathroom and a shower, a fully equipped kitchen, a new fridge and appliances, and a small couch and chairs. Back in Morocco, Omar had worked in retail. Yassine was in the army. Their father had come to Spain in 2005, and for five years sent money home to the family. He learned some Spanish but didn’t fully integrate; now he likes to split his time between Morocco and Spain.

Yassine joined the army mainly because he had few other prospects. After spending five years enlisted in the desert, he couldn’t take it anymore and longed for retirement. Two and a half years ago he asked a psychiatrist for a note saying that the state of his mental health would be in jeopardy if he kept working for the army, and so he was excused from the force. “I felt that I was wasting my life,” he told me. He loved his country but decided he had to pursue better opportunities. “You look for a life with dignity.”

Yassine had initially tried to enter Spain legally, but his visa application was denied. Omar’s savings were depleted by scammers who had promised a crossing by boat. It was Yassine’s plan that eventually got them to the EU by way of Turkey and Hungary, traveling by plane, train, car, and foot. Once in Spain, Yassine told me, he felt suffocated inside the greenhouses and quickly stopped working. He jokes about his hipster look—he wears glasses and a beard—and tells me not to be fooled by appearances. His army life taught him how to survive anywhere.

The brothers insisted that I have Iftar with them that day. Omar made spiced chicken and onions and soup with shrimp. Their father was watching a soccer game on TV and proudly served me his version of Moroccan green mint tea. I can appreciate how hard it is to get it right—I never do. Yassine is learning Spanish and trying to get a certificate that would allow him to work in restaurants. He and his brother hope to move to Germany. They dislike living in Spain. “They hate us,” Omar tells me while cutting fruit, which he covers with yogurt and sugar for dessert.

Adama Sangare Diarra, fifty, is from Daloa, in the Ivory Coast. In 1995 he became one of the first West African migrants to make it to Andalusia to work in the fields, and he watched as more arrived after him. In many cases, he told me in his living room in Almería one Sunday afternoon, the Guardia Civil, one of Spain’s national police forces, sent migrants to Spain after intercepting them in Ceuta and Melilla, Spanish enclaves in North Africa. To Sangare Diarra and several people I interviewed, there is little doubt that the authorities were keen on using undocumented migrants to fill the need for cheap agricultural labor. “It was catastrophic,” he said. “It is not Europe as we imagined it. There are no rights.” A picture of him protesting Spanish labor conditions hangs on the wall in the home he shares with his wife, whom he met in the Ivory Coast twenty-five years ago, and four children.

Sangare Diarra is a rare success story. He studied Islamic Law in Rabat, Morocco’s capital, but felt that his work prospects were limited; back home he could become either an imam or a teacher in a madrassa. His father, an imam who had worked in agriculture back in the Ivory Coast, had spent €300 a month for his son’s education, but Diarra left without completing his schooling. After arriving in Almería by boat he settled in El Ejido and started working in tomato, pepper, and eggplant fields during the day and taking Spanish lessons at night.

He learned Spanish quickly and speaks many other languages, including Arabic, French, and a few West African dialects. Soon he was serving as a translator for organizations that worked with migrants. He became a legal resident in 1997, and eventually a citizen. In the last two decades he’s worked for Almería Acoge, an association partly funded by the Spanish state that helps migrants obtain residency and provides them with food, shelter, and other support.

Sangare Diarra says he tries to soothe the lives of others who, like him, only came to the country to give themselves a chance at a better life. It is challenging work. There is, he tells me, a strong political will to harass and intimidate migrants, and the destruction of El Walili confirmed for him that their community is constantly vulnerable. “Migrants are not integrated…. Many as a result have huge psychological issues,” he said. “Sometimes worse conditions than in Africa. It is not easy to see people live like this.”

Back in Don Domingo de Arriba I met Ahmed, twenty-two, from Kelaat Sraghna, near Marrakech, my hometown. He left two and a half years ago and traveled by sea; he had to sell his car to fund the $2,000 trip. Finally he made it to the Canary Islands. It wasn’t his first attempt. On a previous crossing he had almost drowned and was rescued by the Moroccan Royal Marines.

“When I left I had prepared myself for everything…. I lived better in Morocco but also I had no health care. Some aspects of life were just too hard,” he told me after cooking me my second Iftar of the day. We were in his current home, which belonged to a friend who had left to pick strawberries in Huelva. “When you decide to go into the water, you know there is a 90 percent chance you will drown,” he said. “I was ready for it.”

Ahmed learned to speak Spanish well. He sends money home whenever he can and hopes one day to move back and marry a Moroccan woman. Meanwhile, he is about to get his Spanish residency. In a notebook he keeps under his pillow, he writes his thoughts in Spanish, a way to practice the language but also to write down unfiltered meditations. “Mom, I left home and I didn’t tell you I was going to cross the sea,” he wrote on one page. “I didn’t tell you because I didn’t know where I was going.” The note ends with an emotional wish. “I will be back one day if God wants,” it reads. “I know it’s not possible now but there is nothing I long for more than hugging you.”