When the Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust took over the largest country house in England in 2017, it faced a daunting conservation challenge. A palace-sized 18th-century house near Rotherham in South Yorkshire, Wentworth Woodhouse is nearly 250,000 sq. ft with a 600ft-long façade. It was in a poor state of repair and denuded of the furniture, pictures and other treasures assembled by the Wentworth and Fitzwilliam families over nearly four centuries.

In seven years, despite the challenges of lockdown and periods of high inflation, the trust has put the house on a new footing. Its eye-catching, commonsense approach to conservation focuses on the cultural enrichment of a diverse local community and becoming a regional centre for skills-training and employment while following a carefully staged path to funding the house’s long-term maintenance.

This summer, with Beneath the Surface | George Stubbs & Contemporary Artists, the house launched a new exhibition strand that meets its ambitions to be a cultural powerhouse for the north of England by 2030 and to work with loans of the masterpieces that once hung in the house. The show, which closes this month, marks the 300th anniversary of the great 18th-century British artist.

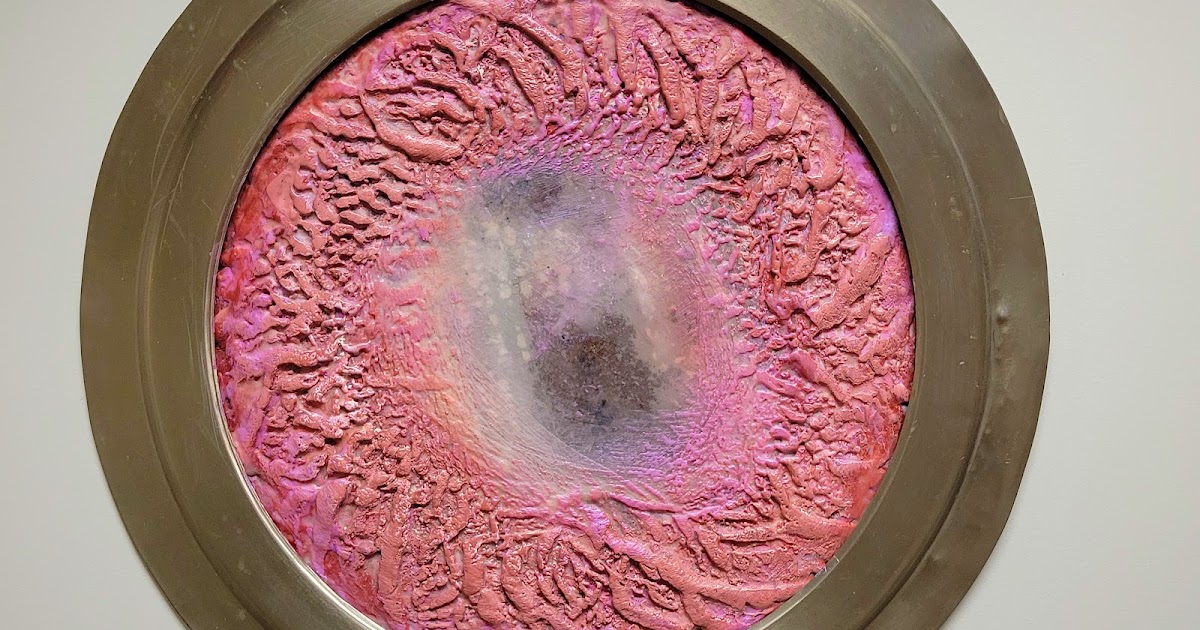

It benefits from the government’s indemnity scheme—an alternative to commercial insurance for art on public display in the UK—allowing the trust to borrow works from private and national collections. The exhibition borrowed four of Stubbs’s finest paintings from a private collection to show them in the house where they were painted in 1762 for Charles Watson-Wentworth, the second Marquess of Rockingham, a wealthy landowner, amateur scientist and future prime minister. There are also loans from museums and collections across the UK, including the Walker Gallery in Liverpool, Weston Park in Staffordshire and Temple Newsam in Leeds. The works are joined by studies of the horse by living artists including Mark Wallinger, Ugo Rondinone and Tracey Emin.

An almost blank canvas

As a historic building, Wentworth Woodhouse is as important as any other great British country house of its era—Blenheim Palace, Stowe House or Chatsworth House—but its celebrated collections of furniture and paintings are almost all gone, as the Fitzwilliam family moved out in the 1940s before finally selling the house in the late 1980s.

The near-empty house is both a challenge and an opportunity. The succession of state rooms, with bare walls and floors—but fireplaces, doors, panelling, classical plaques and some statuary still intact—make ideal galleries for an imaginative curator.

For Sarah McLeod, the chief executive of the trust, the maturing exhibition strand is another potential source of income and of building profile for the start-up business she set up in May 2017, beneath dripping ceilings and peeling paintwork. She had, she says, “five staff, one phone line, no internet connection and one ancient vacuum cleaner”. The trust now turns over £3.5m a year and has raised funds for and completed around £30m of capital works.

“The first question for me,” McLeod tells The Art Newspaper, “was not how do we do this project, but why are we doing it? Right from the start, we decided that it has to be relevant beyond the saving of a piece of stunning architecture.”

“I often say it’s the house of opportunities,” adds McLeod, who was previously chief executive of the Arkwright Society, at Cromford Mills in Derbyshire, an important site of British industrial heritage. “How can this be a catalyst for opportunity for the region, for the borough?”

One of the most striking vindications of that ambition was working with Rotherham Council in February to secure £4.6m of the government’s “levelling-up” investment in the town for work on Wentworth Woodhouse’s stables complex. This vast edifice, designed by John Carr of York to house 84 horses and their grooms, is being developed as a training site for catering and hospitality skills across Yorkshire. Historic England, the public body that oversees heritage, provided an additional £500,000 of partnership funding for the first phase of work on the stables, which is nearing completion this month.

Another opportunity the house provides is for cultural engagement. It could be for the Stubbs exhibition, where some visitors might, McLeod says, “see world-class art for the first time, or it could be participating in a cultural event that we have in the gardens; we do a big festival each year, the We Wonder Festival, which is a celebration of Southeast Asian cultures.” The house has been used as a film and TV set—including for the film of Downton Abbey—and has become a centre for digital skills, using the filming projects as a chance to introduce local schoolchildren and students to the entertainment industry as a potential career.

A cornerstone of the trust’s work is volunteer engagement. Around 300 people have contributed their services, including as house guides and digital volunteers publishing the Wentworth Woodhouse YouTube channel. The channel delivers a mix of history—ranging from Lady Rockingham’s late-18th-century court dress to the story of the local coal-mining industry—and provides progress reports on the building works.

The first capital phase, delivered in part during Covid lockdown, was for immediate repairs to the main part of the house containing the first-floor state rooms, in order to get paying visitors in. Every project since, including the conversion of the camellia house into a tea house and now the stables, has a business rationale. On a typical day there are 50-plus projects of various sizes in motion.

“We take each little project one at a time and we finish them,” McLeod says. “So we may only do three rooms in one building, but we will complete those three rooms … and then get them working, get people in them. So they’re supporting themselves [financially]. That gives us the momentum; something to celebrate. Because keeping the momentum up on a project this big is really difficult.”

The trust has to be as nimble as any start-up. “We’re constantly changing priorities,” McLeod says. “We review projects every Friday morning, and they can change on a weekly basis. A funding stream might suddenly become available, or a donor might come along. And in which case, a project that’s down [the list] might go straight to the top because all of a sudden we can fund it. But generally, we try to do those parts of the business that can generate income the quickest.”

What Wentworth Woodhouse most needs now, McLeod says, is exposure, to encourage first-time visitors—who will then, she hopes, fall under its spell.