From the rare and obscure to the unknown, producer Tee Cardaci mines eleven genre-spanning gems produced during the waning days of Brazil’s military dictatorship, recorded by a new emerging class of artists operating outside of the major label system. Set to release August 4th, via AD and Org Music, we asked Brazilian music authority Allen Thayer to catch up with Cardaci in regards to the three year process it took to make the Sonhos Secretos compilation a reality…

Aquarium Drunkard: So let me start off by asking you how a gringo from Maryland, by way of San Francisco, ended up compiling a compilation of super rare and obscure, independently-released Brazilian 7”s from the 80s?

Tee Cardaci: Well, the way I came to find myself in Brazil in the first place was that in 2008 I had the opportunity to travel to Brazil to play a couple of DJ gigs and to attend a friend’s wedding. And the short version of that story is that I’m still here. A big group of us came down from San Francisco for a couple weeks and my two weeks turned into two months which turned into fifteen years.

When I had the chance to come here, it was kind of a dream fulfilled. I think a lot of people have a romanticized idea about Brazil and, of course, the reality is never quite what you imagine. But I really did fall in love with this country. And as someone who had been digging for decades, it was very humbling and inspiring to come here and almost have to start from zero with the knowledge. Of course, I knew a bit about Brazilian music, maybe more than the average person. But I quickly found out how little I actually knew. Going out digging all the time was really how I got my education in Brazilian music… through the records I was finding and then researching.

Anyways, I’d often find records that we’re these independent productions, and I’ve always had a special place in my heart for private releases ever since I was a twelve-year-old collecting punk 45s growing up outside Washington DC. These weren’t necessarily the records that I was searching for on my digs. As a DJ, I was probably looking for more dancefloor-oriented material. But I recognized these as being special records. They meant a lot to the person that made them. They represented their dreams, which is kind of where the title, Sonhos Secretos, or Secret Dreams in English, comes from. Every time I’d find a record like this in a warehouse, second-hand shop, on the streets or wherever I was digging… when I’d find something that had that homemade quality to it, a really unique sound and that didn’t have a record label attached to it, I would pick it up, take it home, clean it and lovingly file it away.

Then, as I often do with recent finds and new discoveries, I compiled some of these privately-released and independent MPB records on a mix just to share with friends. These were all records that I felt were really special. There were at least four 7”s that had absolutely nothing about them on the Internet that I could find…. certainly not on Discogs. Every song I put on that mix I thought featured great songwriting…. I thought they featured really unique arrangements…. I thought the level of musicianship was superb, and that in a more-just world these people would have found greater fame. I should point out that some like Filó Machado and Moacyr Luz did go on to have fairly successful careers, but their records here represent their first recordings.

This particular mix found its way to Aquarium Drunkard. They asked if they could put it on the site and if I would mind writing some words to accompany it to give it some context. The week that it went online, I got a message from Andrew at Org Music. He said he really loved it and that he thought there was something special there and asked if I would like to work with Org and AD to do a proper, licensed reissue compilation. I’d say that was maybe something I would have considered a dream when I put the mix together, but definitely not something that I had seriously considered until then.

And that’s basically how a gringo from Maryland, via San Francisco, ended up producing a compilation of independently-released Brazilian music. It all came about in a very organic way that, much like the music featured on the compilation, was not created with any commercial consideration or attention to current trends.

AD: Do you remember the first record that fit this bill that you stumbled across and did it make the cut?

Tee Cardaci: I’d say, for every record on the compilation, there are maybe thirty others in my collection that fit the bill but that didn’t make the cut. The ones I chose, I wanted to work as a collection. I wanted you to be able to listen to this album from beginning to end and hear a throughline but I also wanted to show the stylistic breadth of what was happening at this time in the world of independent Brazilian music. Although each track is quite different, to me they all share this sort of dream-like quality, which is the second allusion found in the name Sonhos Secretos…

But to your question, the first record that I found that ended up on the compilation was the Quintais compacto, which is a special one to me. They’re the only artists that are featured twice on the comp. They open the album with the first track on side A, and theirs is the last track on side B. That record I found when… as I often find records in Brazil… I was walking on my way to do something else. There’s a street corner I passed in front of the São Francisco Xavier church in Tijuca where you usually find people with blankets spread out, selling things they’ve scavenged the night before. This one guy had hundreds of random things arranged but literally only one record and it stood out to me right away. Sometimes I feel like the records find me, like it was meant to be me finding that record. Anyways, I took it home and I listened to it and I was just kind of blown away. I mean, it was almost baroque sounding, in a way. It was a little bit prog, but also still Brazilian. Just not in any overt way. It had these vocal harmonies, the coral vocals you get in Brazilian music, but done in a really unique way. And, again, there were some wild arrangements that took these unexpected turns that I found thrilling. Their songs were obviously made with a deep respect for the tradition of Brazilian Popular Music but they were also not really like anything I’d ever heard and they always stuck with me. I’d often go back to that record and put it on to listen to in a quiet moment when I was home alone. So that’s one that I remember finding early on that made it onto the collection.

Another one that’s special is the Renato Faver 7”. This is a record that you still won’t find any info about online. I found this one in a warehouse in downtown Rio. I had my portable with me that day and when I dropped the needle, the track “Espantalho” jumped out at me right away as being something special. It has these great synths, all of the musicians are on point, the recording quality is superb. It was just really well done. Renato was the first musician that I was able to track down when I began the process of trying to find these artists. When I got him on the other end of the phone for the first time, it was really emotional. I think maybe for him, but also for me. I was beginning this journey of trying to find these artists, which was a new process for me, and had finally succeeded in tracking someone down. I remember he was on the phone like, “Wait, so who are you? Where did you find my record? You want to do what with it?!” There was this mix of joy and bewilderment, I think. I told him, “I think your record is amazing. I think it’s beautiful. I think it’s a wonderful record that really deserves to be heard.” He told me that he felt the same, that he had dreams attached to this when he made the record but that his life took him in a different direction that he couldn’t reconcile with being a professional musician. He told me that he and his friends came together to create the best record they could with the limited resources they had and that, to this day, they were really proud of what they had created. You could just feel this sense of validation, like it took forty years but someone had really heard the beauty in what they had made. I imagine it had to have been kind of surreal for him, and the other artists as well, when I finally was able to talk to them.

For most of these artists, this one record was the only thing they had the chance to record and release. For many of them, maybe they continued to play but it was not to be their primary career, despite what they may have hoped for at the time they recorded their 7″.

So, yeah, Quintais was the first record that I remember finding that made it on the compilation and Renato Favor’s record is an extra special one because he was the first artist that I managed to track down as I was beginning this journey. His enthusiasm and support for what I was doing was really encouraging in the early stages.

AD: So what percentage of the artists have you been able to have conversations with at this point?

Tee Cardaci: At this point, nearly all of them. At least those who are still with us.

Since the idea of producing this compilation was presented to me, it’s been a three-year process. Most of that time has been spent trying to track down the artists. Many of these records only included first names or even just the musician’s nicknames, making them extremely difficult to research. Even the records where I had full names to go from, it was insanely time-consuming to locate these guys. I’m sure I easily have over a thousand hours in this. So many sleepless nights, endlessly Googling names, posting on every Facebook group even potentially tangentially related to the record, sending emails to journalists from that era who had culturally-related bi-lines in newspapers in the cities where these records came from. And on, and on, and on.

The one record that I probably have the most time invested in is the Jorge Bahiense & Ricardo Luiz 7”. My friend, Junior Santos, who’s done some brilliant reissue work that’s been a model for me on how to do a project like this correctly, was instrumental in helping me solve this puzzle. My research started off well, seeing right away that someone had posted this record on YouTube but then the trail ended there. After countless hours of fruitless research on my own, I messaged Junior with a photo of the cover and, while he didn’t know the record, he recognized one of the names in the credits and was able to get me the contact for one of the musicians. That turned out to be Glaucus Xavier who played sax and piano on the record in addition to handling some of the arrangement. I got in touch with Glaucus who promised to try and help me find these guys, despite not being in touch with either of them in ages. He finally got back to me to let me know that, sadly, he’d found out that Jorge Bahiense had passed away a few years ago but that he had the contact for his daughter. I got in touch with her and, while she loved the project and the idea of her father’s music being reissued, she said that for reasons related to Brazilian bureaucracy, she would not be able to license his music on his behalf. But she told me she’d try to help me track down Ricardo Luiz. At this point I still knew nothing about the story behind the record. Months passed and the audio restoration work was complete and we were ready to send the masters off to make the test pressings. Decisions had to be made as to the final track selection. I was nearly ready to give up on this one when Bahiense’s daughter got back in touch with an email address for Ricardo Luiz. When I messaged him, he hit me back right away, eager to talk on the phone to better understand what the story was with this project. I don’t think I’ve ever been so excited to make a phone call. After I got through explaining what I thought of his record, what I was trying to do and what I’d been through trying to find him, what he told me blew my mind. He and Bahiense were not professional musicians but had both been teachers at the same high school in São Paulo when they met. They used to play their guitars together between classes and work on each other’s compositions just for the love of music. When they decided to make their own record, they used some of their high school students to back them because neither of them even knew any professional musicians! Knowing how good this record was, this information just floored me…. like, “You got to be kidding. These are just kids on this?!” When the time came to press their record, Ricardo told me that Jorge sold his motorcycle to finance it. Hearing stories like these about what it took for these artists to press their own records then was incredible.

Mauricio Herdy is another interesting story, because he was actually from the city I live in now, Nova Friburgo. I found his record while digging locally and, again, there was nothing online about it at the time. The song, “Amor De Verão, was co-written by Giovanni Bizzotto, who I was able to track down. He told me that Mauricio had been a good friend of his but that he had passed away in the 90s. Giovanni co-wrote and arranged the song and played saxophone and guitar on it as well. His contributions are what makes the record so interesting to me. We only met in person for the first time a few weeks ago when he played a show in town with Marvio Cirabelli. I was able to give him a copy of the 7”. Even he didn’t have one. So that was a special encounter. Although I’d spoken with him on the phone quite a bit and he was excited about the project and was happy for Mauricio Herdy’s family to know that his music would live on, I don’t think it really hit him until we met in person and I showed him the artwork for the cover of the compilation and I handed him a copy of his own record. You could tell that he was kind of taken aback. And, you know, it was an emotional moment. For both of us.

So yeah, I’ve had a chance to speak to almost all of the artists at this point. The beauty of focusing on independent artists that I only realized in hindsight is that I had the pleasure of working with them directly to license their music and, in the process, get to know them a bit and hear their stories.

AD: Can you take a minute to explain to everyone, what MPB means? The definition, but also what it represents to you as a listener. And how do the songs on this compilation relate to MPB? Is there a throughline of genres that you can use to describe these songs? Are they coming from the same scenes or similar scenes in different cities or is there really just a more abstract mix?

Tee Cardaci: As best I understand, Brazil is the only country in the world with its own specific genre, which is Música Popular Brasileira, or Brazilian Popular Music. There’s an expression I’ve heard, “MPB é tudo” which means “MPB is everything”. Its kind of a blanket term that encompasses a lot of post-bossa nova Brazilian music… and when they say ‘popular’ in Brazil, they don’t mean popular like we think of it, but in the sense of being of the people. It’s essentially a fusion of various Brazilian styles with elements of jazz, sometimes a soulful influence. Some of it is more rock oriented. But it’s this term that’s used to identify just a wide range of styles of contemporary Brazilian music.

What it means to me in the context of this compilation is just contemporary music that was made in Brazil during this specific time. But, interestingly, you don’t listen to a lot of these songs and, except for the fact they’re singing in Portuguese, say, “Oh, that’s a Brazilian song.” There’s no overt samba rhythms, except maybe in a passage on the Hilton Barcellos track, and even that one comes as an unexpected change-up. Also, I think it’s interesting that although these songs all came out between 1980 and 1985, I don’t think most of them have the stylistic or sonic traits we would associate with being an early eighties production. To me, they all sort of have this timeless quality, and I think that’s always a hallmark of great music.

So, in keeping with that wide range of styles that fall under this umbrella of ‘MPB’, the songs on this compilation all feature a mix of various influences. All music that I really enjoy tends to share one common denominator. It tends to occupy the spaces between genres and defy easy classification. And I think these songs do that. Some of them might have more of a jazz influence. But they’re definitely not jazz records. Some of them have a soulful element to them. But none of these are soul records. None of these are regional Brazilian rock records, though they may contain hints of that style. So yeah, I think these records work together as a collection yet they are, you know, each quite different and unique in their sound. But they all share in common the fact that they were independently released in Brazil at this very specific, unique time, both culturally and politically, and they’re all just really pure examples of artistic expression, made without any commercial consideration.

AD: Could it be that they sit stylistically between genres might have contributed to the fact that they weren’t wildly successful?

Tee Cardaci: I guess it could have, but I think in most of these cases, they never had a chance to begin with and I’ll tell you why. I think that without a marketing budget, without proper distribution channels in place, there was no way that these records were ever really gonna get heard beyond a relatively small circle, being mostly family, friends and those that bought copies of these records at shows. A similar story to private press records released anywhere.

I can tell you something else that I noticed. When I would find these records, they almost always looked unplayed. You can read into that a number of ways but I think there might be a lesson there in how we don’t always appreciate the talents of those closest to us. This is sort of a whole other story here but when you’re re-issuing something, you have to decide what’s the best source material you have to work with. Obviously, I wanted the master tapes. Unfortunately, those were only available to us in two cases. These artists that recorded these songs didn’t have the luxury of storing their tapes in a climate-controlled vault in some record label facility, you know? If you’ve ever been to Brazil, you know that the humidity is no joke, and most of these tapes were just lost to time, lost to mold. So for the records that we didn’t have tape for, we had to do high-resolution transfers from the original records. And I need to definitely give credit here to Dave Gardner, who did the transfers and audio restoration on this project. He did an incredible job. He was able to at least work from a record that was, in most cases, a near-mint copy when the tape no longer existed.

AD: The focus of this compilation is between 1980 and 1985. What is unique about independently recorded and produced music from this period in time in Brazil?

Tee Cardaci: Well, a few things. But honestly, in terms of the compilation representing independently released music from 1980 to 1985, that was sort of coincidental when I chose the records to put on that first mix that I had made. At least it wasn’t something that I was consciously considering. But then, when I started to think about that more, it kind of made sense that these artists represented the second wave of artists in Brazil that were willing to go it alone and self-release their own music. First, there was Tim Maia and his Racional records, followed closely by Antonio Adolfo’s Feito Em Casa LP, which opened the door and kind of paved the way for these artists, showing that it was possible to release your own music without a record label.

I can’t say if all of these artists were directly inspired by artists like Antonio Adolfo, but he is directly connected to two records on Sonhos Secretos. With Renato Faver’s record, Antonio Adolfo was the one that worked with them to help them get ready to record. Faver had never been in a recording studio before. And then Antonio Adolfo was also the one that hooked them up with the great drummer, Chico Batera, and took them to his Studio Tok where they recorded the record.

Antonio Adolfo also pops up again on Marcello Lessa’s song, “Azulão”. Incidentally, Marcello Lessa was not on the original mix that I put together. This was a record I discovered further into the process and really pushed to have included. I found it on a dig in downtown Rio outside of the Carioca Metro station and I took it home and just fell in love with it. And when I flipped it over to check the credits, I see Antonio Adolfo is playing the piano. Wilson das Neves is on drums and percussion. Nivaldo Ornelas is playing flute. So here we have some major names in Brazilian music on this record that, to this day, is still nowhere to be found online, which is kind of crazy. This is also an emotional one for me. Every time I hear this song it brings tears to my eyes, not just because it’s such a beautiful, moving song, which it absolutely is. When I finally tracked down Marcello Lessa and told him that I’d found his record and wanted to use it on my compilation, he wrote me back that it would be an honor and a pleasure to be a part of this project. He was really excited to have his music potentially heard by a new audience and be rediscovered. We communicated back and forth a bit before suddenly I wasn’t getting any responses. I wasn’t sure what was going on. And this is the middle of the pandemic still. Eventually I received a message from his account but it was from his wife saying, “I’m sorry to inform you that Marcelo passed away.” That was a tough one. But there was something in at least knowing that he knew his music was going to be brought to a new audience. Obviously, it’s heartbreaking that he won’t get to see and hear the finished compilation and, you know, receive the accolades he deserves. He’s an incredible musician, singer and songwriter that played with some of the greats as a side man but this one 7” was the only solo project he ever released on vinyl. But if you can get legends like Antonio Adolfo and Wilson das Neves to come and record on your record, which likely had a very small budget, you’re obviously held in high regard by these masters.

Really, this just brings to mind what this compilation is all about. For me, it’s about getting these artists that I think are very deserving of our attention, the audience that maybe they never had the first time around, or at least a wider audience. And that’s really what’s kept me going on this project over these three years, bringing this music to a new audience eager to dive deeper and discover more incredible sounds from Brazil.

And I have to say… I mentioned the pandemic…. the pandemic started very shortly after this project got going, and this is one thing that I was able to really dive into to keep myself busy. But it was also taking place with, you know, all the other things we were dealing with then, a lot of anxiety in general about what was happening in the world. I was getting deep into the project but things were moving very slowly and I began to have these moments like, “What have I got myself into here? I’ve shown up out of nowhere with some idea to resurrect these artists’ past and now I can’t let them down.” I was starting to feel this crazy pressure like “I NEED to get this project across the finish line!” I’ve convinced all these people to trust me with their music and, you know, literally their dreams that they had when they made these recordings. I told them I was going to get this out and now I need to actually make this happen. So I want to thank Andrew at Org and Justin at Aquarium Drunkard for sticking by me, because there were definitely times when I didn’t know if I’d be able to complete this. There’d be times when I wouldn’t speak to them for months because I had no new news to report, and then I’d be dreading getting on a call, like they’re just gonna tell me, “You know what, we can’t put any more time into this.” But they were very patient and they were very supportive the whole way through and they just allowed this project to take as much time as it needed. Even down to the artwork for the cover, you know?

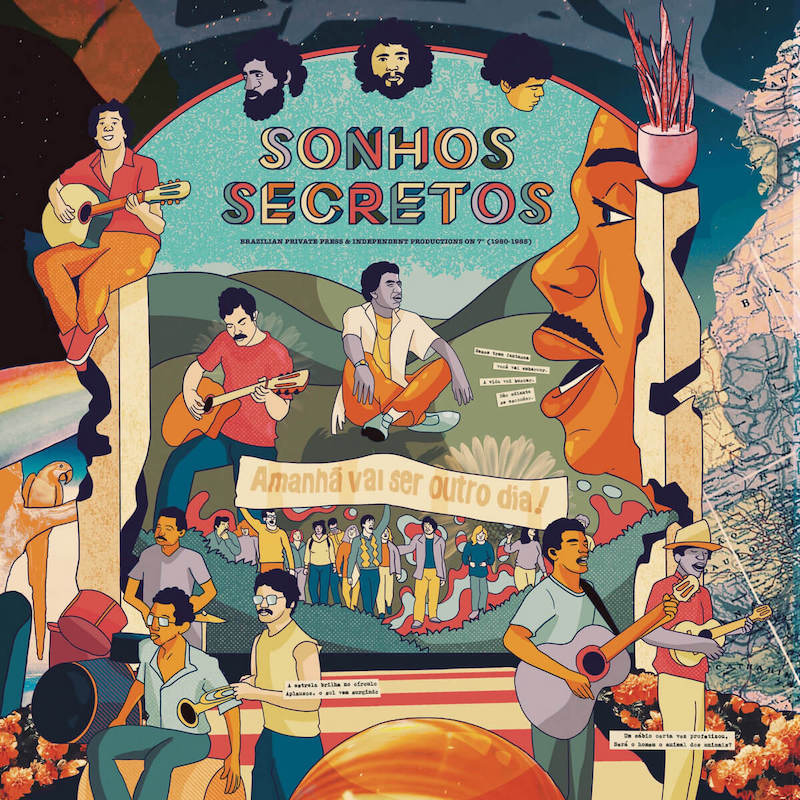

AD: Tell me about the cover. There’s a lot going on there.

Tee Cardaci: Once I’d pretty much done everything on my end, Org had a great designer working on the cover but the concepts just weren’t connecting with the project in the way that I hoped they would. I just felt like this project… we had so much in it, the cover had to be right. And I asked them, “Would you trust me to try to find a Brazilian artist to do this? Because I think it needs to be a Brazilian artist that’s gonna connect with this music and really understand what this project is about.” And to their credit they said, “Yeah, don’t worry, we’ll talk to our designer and let them know that we’re gonna go in a different direction.” At this point, the test presses had already been OKed and the record was ready to go to press. We just needed the art and layout. That’s when I got in touch with Daniel Vincent Gomes, an illustrator from Pernambuco who I knew of from his work on the cover of Guinu’s Palagô LP that I executive produced for Razor n Tape. I got in touch with him and he said, “I don’t have the time, really, but send me the music. Let me check it out”. After he listened to it, he got back in touch straight away. And he’s like, “What is this? This is amazing. I’ve never heard any of these songs before. This music is incredible.” He said he’d do whatever was necessary to be a part of the project. He told me he listened to the tracks on the album on repeat while working on the design, inserting loads of symbolism and clues into the artwork for the curious listener to uncover, which is always something I’ve appreciated in an album cover. He also did a brilliant job of referencing every artist on the record and connecting everything to what was going on socially and politically in Brazil at the time.

This also brings me back to your question about what was particularly interesting about this window from 1980 to 1985. This is getting into the final days of Brazil’s horrendous military dictatorship. Under the regime, all forms of art faced heavy censorship. Any book or record had to be presented to the military police to be reviewed, and anything they thought went against the regime in any way or would potentially corrupt the obedient Brazilian citizen was heavily censored. But at this time in the early eighties, this was the last waning days of the dictatorship and the censors were letting up a bit as the regime was losing its grip on power. Artists were taking to the streets as part of a movement called “Diretas Já!”, demanding their rights and calling for free and open elections. So this new sense of artistic freedom that was happening, that’s represented in these songs.

The songs on this compilation are so special to me on so many levels but mainly because they really represent something pure. And it’s a unique snapshot in time of what was happening in Brazil and it’s one very few people have had the opportunity to hear until now.

AD: It reminds me of something Yale Evelev from Luaka Bop said when we were talking about Tim Maia’s Racional releases, that there is something really special about music that is made outside the confines of the music industry. You know, like, if it’s not about money, it will turn out differently.

Tee Cardaci: Absolutely. I think when you’re making a record without any external influence, without anyone putting pressure on you as to what it should sound like, or what it needs to sound like, or what it needs to include on it, the outcome is often something very special and I think that’s definitely the case with the songs on Sonhos Secretos.

Only the good shit. Aquarium Drunkard is powered by our patrons. Keep the servers humming and help us continue doing it by pledging your support via our Patreon page.