Around 1772, Phillis Wheatley, an enslaved teenager in Boston, sat down to write a poem called “On Being Brought from Africa to America,” which began with praise for the “mercy” that brought her from “my Pagan land” into Christian redemption.

The poem — once called “the most reviled poem in African American literature” — has been hard for many to take, including the generations of Black poets who have claimed Wheatley as a foremother. So when the historian David Waldstreicher used to teach it to undergraduates, he would read it in two different voices.

“One was an exaggerated, beseeching voice — ‘Oh, thank God I escaped Africa!’” he recalled recently. The other was “ironic and challenging” — and, in his view, true to the subversive, antislavery thinking behind Wheatley’s decorous neoclassical couplets.

“By the end of class,” Waldstreicher said, “I got them to see there was a lot more going on.”

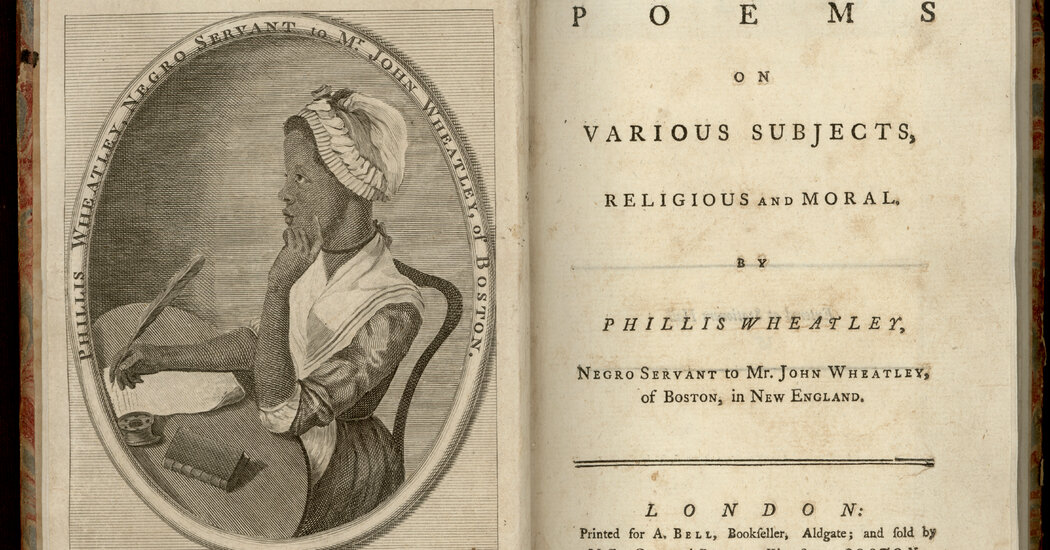

Wheatley — celebrated as the first African American to publish a book of poetry — has long inspired a steady stream of scholarship, tributes and creative remixes. Now comes Waldstreicher’s new book, “The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley,” out Tuesday, which puts her smack in the middle of the raging debate over the relationship between the American Revolution and slavery.

That question has become a 21st-century hot potato, fiercely contested everywhere from scholarly panels to Broadway to the White House. It’s a deeply polarizing one on which Waldstreicher takes a nuanced, hard-to-pin-down position.

“There are those who want to say it’s pro-slavery, and those who want to say it’s antislavery,” he said of the Revolution. “But it’s much messier than that. It was going in both directions.”

Waldstreicher, who teaches at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, is known for deeply researched, tightly written studies, which aim to complicate any comforting idealization of the founding.

“He has big ideas, but he has never shied away from the hard archival work necessary to make them persuasive and influential,” said Karin Wulf, director of the John Carter Brown Library, a leading research center for early American history.

But his books (which include a study of Ben Franklin and slavery) and his blunt intellectual style haven’t always made him popular. Some traditionalists in the field, he said tartly, prefer to “pretend I don’t exist.”

Waldstreicher is also a longtime scourge of “Founders’ Chic,” as historians refer to reverential best sellers extolling the character of the founders (often by exaggerating their opposition to slavery). . But his new book, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, is itself a founder biography of sorts, treating Wheatley not only as the progenitor of the African American literary tradition but an important political voice in the creation of the nation itself.

Her poems were read by Franklin (who met her in London), George Washington (to whom she sent an admiring elegy) and Thomas Jefferson (who posthumously mocked her). They weren’t just literary gestures, Waldstreicher argues, but “actions in the drama” of revolutionary America.

His book begins with a crisp reprise of the Wheatley story. Kidnapped from West Africa around age 7, she arrived in 1761 in Boston, where she was bought by John Wheatley, a prosperous merchant, and his wife, Susanna.

After Phillis was observed writing “letters” on the wall, one of the Wheatley daughters taught her to read English. In December 1767, when she was about 14, she published a poem about a shipwreck in a newspaper. Stories about her precocious brilliance began to circulate.

The Wheatleys helped arrange publication of her book in 1773, when she traveled to London to promote it. Soon after returning, she was freed, and in 1778 married a formerly enslaved grocer named John Peters, with whom she had perhaps four children, none of whom survived. She died, impoverished, in Boston in 1784, at age 31.

Waldstreicher started studying Wheatley around 2009, after he had finished his book “Slavery’s Constitution.”

As part of his research, he looked at every page of every newspaper published in the Boston area from her arrival to her death (some 50,000 pages in all), finding many previously unnoticed “footprints.” He also found what he tentatively argues are 13 anonymously published Wheatley poems.

Waldstreicher is not the only scholar who has been expanding the documentary record. Last year, the literary scholar Wendy Roberts announced the discovery of what she says is the earliest known full-length Wheatley elegy, from 1767.

And in 2021, the historian Cornelia Dayton uncovered records of a legal case that help illuminate Wheatley’s “lost” final years, as well as the complicated end of slavery in Massachusetts in the 1780s.

Waldstreicher draws on Dayton’s work, which argues that Wheatley’s husband, long dismissed as a ne’er-do-well who abandoned her, attempted to provide her with financial security and spared her typical household drudgery, to support her continuing literary ambitions.

In addition to tracing her life, Waldstreicher also recreates the 18th-century intellectual world Wheatley actually lived in. A key moment, he said, came when he bought an old Books on Tape recording of Homer’s “Odyssey” at a library sale.

“I had been taught to believe this stuff was irrelevant, except to the most elite founding fathers,” he said. But while listening, he said, something clicked.

“This is about women, this is about slavery, this is about voyages,” he said. “This would have spoken to her.”

A number of historians have written trade books focused on Black women in the orbit of the founders, including Erica Armstrong Dunbar’s “Never Caught” (about Ona Judge, an enslaved woman who ran away from Washington’s household) and Annette Gordon-Reed’s “The Hemingses of Monticello.”

Wheatley’s story, Waldstreicher argues, similarly complicates any dichotomy between bottom-up social history and top-down political history. She was an international literary celebrity, embraced by many white readers as an important patriotic voice. But she was also enmeshed in networks of ordinary Black people, free and enslaved, who were having their own debates over independence, slavery and freedom.

In her new book “Reading Pleasures: Everyday Black Living in Early America,” Tara S. Bynum, an assistant professor of English and African American Studies at the University of Illinois, discusses Wheatley’s long correspondence with her “friend & Sister” Obour Tanner, who may have arrived in Boston on the same ship.

“I’ve asked various audiences who they think of when I say the words ‘the Revolutionary War,’” Bynum said. “They almost never think of two Black women. Yet these are two Black women who are having to navigate the war that brings forth the founding.”

Waldstreicher also challenges some aspects of the entrenched Wheatley narrative, starting with the idea that in 1772, 18 leading white citizens subjected her to an “oral examination” (as the scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. described it in his 2003 book “The Trials of Phillis Wheatley”), demanding proof she had actually written her poems.

The men did sign an “attestation” endorsing her authorship, but there is no evidence, Waldstreicher writes, of any group inquisition. In fact, he writes, some of them already knew Wheatley, and had been “talking her up for years.”

In the 18th century, it may have taken white men to “legitimize” her. But ever since, Waldstreicher said, it has mostly been Black women who “kept her memory alive.”

In 1924, the educator Mary Church Terrell created a historical pageant about Wheatley’s life, as part of the bicentennial of Washington’s birth. In 1949, the writer Shirley Graham Du Bois published an influential young-adult biography, “The Story of Phillis Wheatley.”

And since 1973, when a group of 20 prominent Black women writers gathered to mark the bicentennial of Wheatley’s book, poets including June Jordan, Nikki Giovanni and Honorée Fanonne Jeffers have reimagined her.

Black men, Waldstreicher notes, have sometimes been less enthusiastic, rejecting Wheatley as an embarrassment, or worse. In the 1960s, during the Black Arts movement, one critic derided her as “an early Boston Aunt Jemima” who was “utterly irrelevant to the identification and liberation of the Black man.”

That idea that Wheatley “wasn’t Black enough,” Bynum said, has faded. But Waldstreicher acknowledges that her neoclassical rhymes and religious piety still makes some modern readers “run from the library stacks.”

As for his own book, he said he hopes it helps restore Black Americans to their complicated place at the heart of the founding, while countering reductive claims that the Revolution was either a noble freedom struggle or hypocrisy all the way down.

But then that debate, Waldstreicher said, would have been familiar to Wheatley and everyone else in 1770s America.

“They were arguing,” he said, “about the same things we’re arguing about today.”