You see it everywhere, even if you don’t always recognize it: the literary allusion. Quick! Which two big novels of the past two years borrowed their titles from “Macbeth”? Nailing the answer — “Birnam Wood” and “Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow” — might make you feel a little smug.

Perhaps the frisson of cleverness (I know where that’s from!), or the flip-side cringe of ignorance (I should know where that’s from!), is enough to spur you to buy a book, the way a search-optimized headline compels you to click a link. After all, titles are especially fertile ground for allusion-mongering. The name of a book becomes more memorable when it echoes something you might have heard — or think you should have heard — before.

This kind of appropriation seems to be a relatively modern phenomenon. Before the turn of the 20th century, titles were more descriptive than allusive. The books themselves may have been stuffed with learning, but the words on the covers were largely content to give the prospective reader the who (“Pamela,” “Robinson Crusoe,” “Frankenstein”), where (“Wuthering Heights,” “The Mill on the Floss,” “Treasure Island”) or what (“The Scarlet Letter,” “War and Peace,” “The Way We Live Now”) of the book.

Somehow, by the middle of the 20th century, literature had become an echo chamber. Look homeward, angel! Ask not for whom the sound and the fury slouches toward Bethlehem in dubious battle. When Marcel Proust was first translated into English, he was made to quote Shakespeare, and “In Search of Lost Time” (the literal, plainly descriptive French title) became “Remembrance of Things Past,” a line from Sonnet 30.

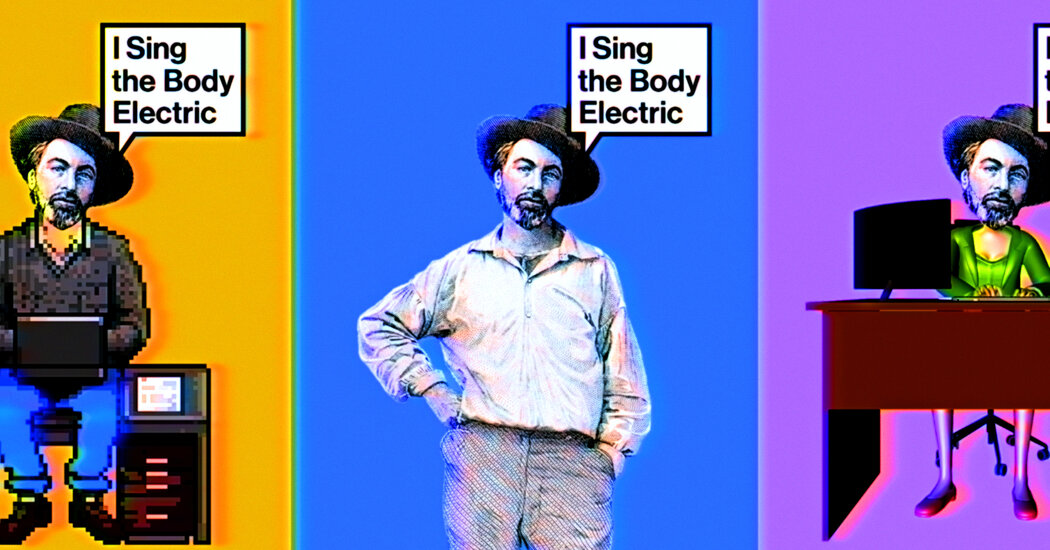

Recent Proust translators have erased the Shakespearean reference in fidelity to the original, but the habit of dressing up new books in secondhand clothing persists, in fiction and nonfiction alike. Last year, in addition to “Birnam Wood,” there were Jonathan Rosen’s “The Best Minds,” with its whisper of Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl,” Paul Harding’s “This Other Eden” (“Richard II”), and William Egginton’s “The Rigor of Angels” (Borges). The best-seller lists and publishers’ catalogs contain multitudes (Walt Whitman). Here comes everybody! (James Joyce).

If you must write prose and poems, the words you use should be your own. I didn’t say that: Morrissey did, in a deepish Smiths cut (“Cemetry Gates,” from 1986), which misquotes Shakespeare and name-checks John Keats, William Butler Yeats and Oscar Wilde — possibly the most reliably recycled writers (along with John Milton and the authors of the King James Bible) in the English language.

Not that any of them would have minded. When Keats wrote that “a thing of beauty is a joy forever,” he surely hoped that at least that much of “Endymion” would outlive him. It’s a beautiful sentiment! And he may have been right. Does anyone read his four-part, 4,000-line elegy for Thomas Chatterton outside a college English class, or even for that matter inside one? Nonetheless, that opening line may ring a bell if you remember it from the movies “Mary Poppins,” “Yellow Submarine” or “White Men Can’t Jump.”

Wilde’s witticism and bons mots have survived even as some of his longer works have languished. If it’s true (as he said) that only superficial people do not judge by appearances, maybe it follows that shallow gleaning is the deepest kind of reading. Or maybe, to paraphrase Yeats, devoted readers of poetry lack all conviction, while reckless quoters are full of passionate intensity.

Like everything else, this is the fault of the internet, which has cannibalized our reading time while offering facile, often spurious, pseudo-erudition to anyone with the wit to conduct a search. As Mark Twain once said to Winston Churchill, if you Google, you don’t have to remember anything.

Seriously though: I come not to bury the practice of allusion, but to praise it. (“Julius Caesar”) And also to ask, in all earnestness and with due credit to Edwin Starr, “Seinfeld” and Leo Tolstoy: What is it good for?

The language centers of our brains are dynamos of originality. A competent speaker of any language is capable of generating intelligible, coherent sentences that nobody has uttered before. That central insight of modern linguistics, advanced by Noam Chomsky in the 1950s and ’60s, is wonderfully democratic. Every one of us is a poet in our daily speech, an inglorious Milton (Thomas Gray), a Shakespeare minting new coins of eloquence.

Of course, actual poets are congenital thieves (as T.S. Eliot or someone like him may have said), plucking words and phrases from the pages of their peers and precursors. The rest of us are poets in that sense, too. If our brains are foundries, they are also warehouses, crammed full of clichés, advertising slogans, movie catchphrases, song lyrics, garbled proverbs and jokes we heard on the playground at recess in third grade. Also great works of literature.

There are those who sift through this profusion with the fanatical care of mushroom hunters, collecting only the most palatable and succulent specimens. Others crash through the thickets, words latching onto us like burrs on a sweater. If we tried to remove them, the whole garment — our consciousness, in this unruly metaphor — might come unraveled.

That may also be true collectively. If we were somehow able to purge our language of its hand-me-down elements, we might lose language itself. What happens if nobody reads anymore, or if everyone reads different things? Does the practice of literary quotation depend on a stable set of common references? Or does it function as a kind of substitute for a shared body of knowledge that may never have existed at all?

The old literary canon — that dead white men’s club of star-bellied sneetches (Dr. Seuss) — may have lost some of its luster in recent decades, but it has shown impressive staying power as a cornucopia of quotes. Not the only one, by any means (or memes). Television, popular music, advertising and social media all provide abundant fodder, and the way we read now (or don’t) has a way of rendering it all equivalent. The soul selects her own society (Emily Dickinson).

When I was young, my parents had a fat anthology of mid-20th-century New Yorker cartoons, a book I pored over with obsessive zeal. One drawing that baffled me enough to stick in my head featured a caption with the following words: “It’s quips and cranks and wanton wiles, nods and becks and wreathed smiles.” What on earth was that? It wasn’t until I was in graduate school, cramming for an oral exam in Renaissance literature, that I found the answer in “L’Allegro,” an early poem by Milton, more often quoted as the author of “Paradise Lost.”

Not that having the citation necessarily helps. The cartoon, by George Booth, depicts a woman in her living room, addressing members of a multigenerational, multispecies household. There are cats, codgers, a child with a yo-yo, a bird in a cage and a dog chained to the sofa. Through the front window, the family patriarch can be seen coming up the walk, a fedora on his head and a briefcase in his right hand. His arrival — “Here comes Poppa” — is the occasion for the woman’s Miltonic pep talk.

Who is she? Why is she quoting “L’Allegro”? Part of the charm, I now suspect, lies in the absurdity of those questions. But I also find myself wondering: Were New Yorker readers in the early 1970s, when the cartoon was first published, expected to get the allusion right off the bat? They couldn’t Google it. Or would they have laughed at the incongruous eruption of an old piece of poetry they couldn’t quite place?

Maybe what’s funny is that most people wouldn’t know what that lady was talking about. And maybe the same comic conceit animates an earlier James Thurber drawing reprinted in the same book. In this one, a wild-eyed woman bursts into a room, wearing a floppy hat and wielding a basket of meadow flowers. “I come from haunts of coot and hern!” she exclaims to the baffled company, disturbing their cocktail party.

That’s it. That’s the gag.

Were readers also baffled? It turns out that Thurber’s would-be nature goddess is quoting “The Brook,” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson. (I’ve never read it either.) Is it necessary to get the reference to get the joke? If you chuckle in recognition, and complete the stanza without missing a beat — “I make a sudden sally/And sparkle out among the fern,/To bicker down a valley” — is the joke on you?

It’s possible, from the standpoint of the present, to assimilate these old pictures to the familiar story about the decline of a civilization based in part on common cultural knowledge. Sure. Whatever. Things fall apart (Yeats). In the cartoons’ own terms, though, spouting snippets of poetry is an unmistakable sign of eccentricity — the pastime of kooky women and the male illustrators who commit them to paper. This is less a civilization than a sodality of weirdos, a visionary company (Hart Crane) of misfits. But don’t quote me on that.