Her family announced the death in a statement shared by the Black Film Center & Archive at Indiana University, which had previously hailed her as “the first African-American woman to direct an independent feature film in the post-civil rights era.” The statement did not cite a cause.

Ms. Maple, who was also known by her married name of Jessie Maple Patton, was working as a lab technician when she decided she “wanted something more exciting,” as she later told the New York Times. She turned first to journalism and then to film, working as a camera operator and a documentarian before releasing her first feature, “Will” (1981), a family drama that she made for less than $12,000.

For decades, film crews had been composed almost entirely of men, primarily White men, from the director down to the sound mixers, electricians and camera operators. By the early 1970s, that had started to change, with lawsuits helping to pry open doors that had long been closed to women and African Americans.

Ms. Maple was part of that new cinematic vanguard and got her start in training programs run by WNET, New York’s public television station, and Third World Cinema, a film company started by actor Ossie Davis. She worked as an apprentice editor on a pair of Gordon Parks films, “Shaft’s Big Score!” and “The Super Cops,” but found that she had little interest in the role, which confined her to a dark office and film laboratory.

“I had already left the bacteriology lab and I did not want to be sitting in another little lab,” she said in a 2005 interview for Black Camera, a film journal. “I wanted to be out there [in the streets]. They would get mad with me because I said, ‘I’m not doing that, I’m going to do camera.’”

By 1975, she had joined the cinematographers union, which promptly blacklisted her, by her account, after she fought to change guild rules that would have required her to spend years as an assistant.

“If I had waited, I would never have become a cameraperson,” she told the Times in 2016. “So I took ’em to court. At the [time], they said minorities could not learn how to use the cameras.”

Ms. Maple sued several local TV channels, citing gender and racial discrimination, and won a legal victory that she later detailed in a short book, “How to Become a Union Camerawoman” (1977), intended to make the process easier for the generation that followed. She was soon getting regular assignments, even as she found herself getting strange looks — or worse — from colleagues who asked why a Black woman would want to wield a film camera.

“I get motion sickness. So every day, they would send me up in the helicopter,” she recalled, looking back on her work for New York’s CBS affiliate. “I would get my story, and then when I would get off, I would be so sick. But they had to pay me $60 anytime I went up, so I was making money.”

In partnership with her husband, photographer and cinematographer Leroy br, she started making documentaries including “Methadone: Wonder Drug or Evil Spirit” (1976), a skeptical look at methadone’s role in treating opioid addiction. Her interest in the subject led to “Will,” which told the story of a basketball coach (played by Obaka Adedunyo) who struggles to stop using heroin and who mentors a young boy with support from his wife (Loretta Devine, in her film debut).

“It’s a hard-hitting, slice-of-life drama that’s also notable for its unapologetic depiction of underage drug use among black male youth,” film critic Tambay Obenson wrote in a 2020 article for the website IndieWire. “Maple’s love for her neighborhood and her neighbors is obvious,” he continued, “as she paints an unflinching portrait of the struggle and resiliency of the community.”

The film established Ms. Maple as one of the first in a wave of Black female directors that included Alile Sharon Larkin, Kathleen Collins, Fronza Woods and Julie Dash, whose 1991 film, “Daughters of the Dust,” is considered the first feature directed by a Black woman to be distributed theatrically in the United States.

Ms. Maple went on to make one more low-budget drama, “Twice as Nice” (1989), about twin sisters trying to break into the world of women’s pro basketball. Released seven years before the founding of the Women’s National Basketball Association, it starred the real-life twins Pamela and Paula McGee, who helped lead the University of Southern California women’s basketball team to back-to-back NCAA titles, and their teammate Cynthia Cooper-Dyke, a future MVP in the WNBA.

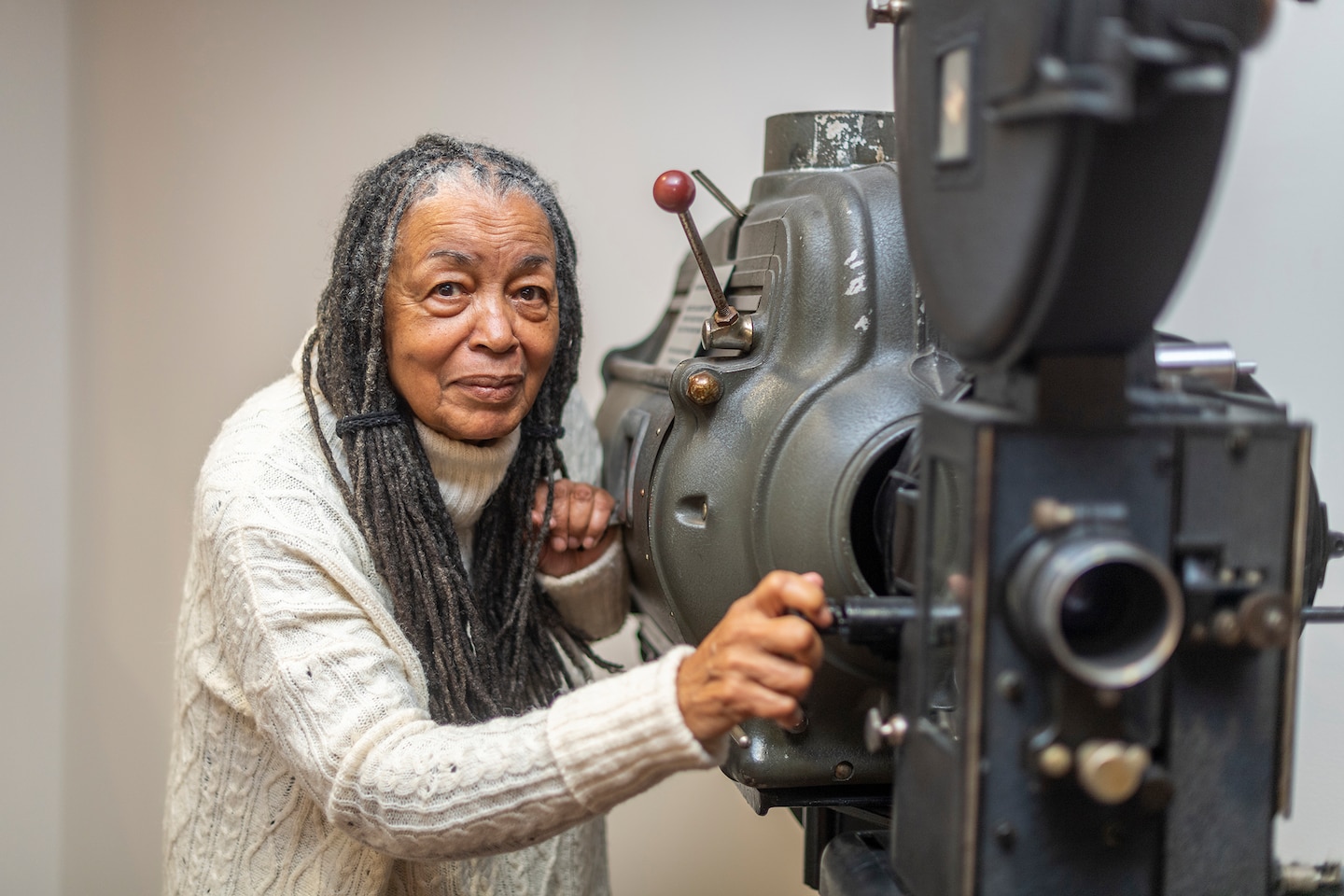

The film was shot in part at Ms. Maple’s home, a Harlem brownstone with a spacious basement that she and her husband converted into a movie theater named 20 West, after their address on 120th Street.

Ms. Maple ran the theater for about a decade, beginning in 1982, and used the space to showcase a rich array of Black independent films, from contemporary work by Spike Lee to early 20th-century “race movies” that anticipated her own films by 60 years or more.

“We ended up creating a viewing space large enough to seat fifty,” she wrote in a memoir, “The Maple Crew” (2019), with co-author E. Danielle Butler. “Our guests became our members, and we wanted them to feel at home. We made our own popcorn, and people bought their own pillows. This space was as much for them as it was for us. It was ours.”

Ms. Maple was born in McComb, Miss., on Feb. 14, 1937. Her father, a farmer, died when she was 13. Her mother was a schoolteacher and dietitian who sent Ms. Maple and some of her 11 siblings north to continue their education.

After graduating from high school, Ms. Maple studied medical technology at the Franklin School of Science and Arts in Philadelphia. She worked for six years as a lab technician in bacteriology before going into print journalism, writing an entertainment column called Jessie’s Grapevine for the Black-owned New York Courier.

Around that same time, she met Patton, a photographer for publications including Jet and Ebony. They later supplemented their filmmaking income by running a pair of Harlem diners; after moving to Atlanta, they started a vegan dessert business.

In addition to Patton, her husband of more than 40 years, survivors include Audrey Snipes, a daughter from an earlier marriage that ended in divorce; five sisters; and a grandson.

Ms. Maple produced music videos and continued to take occasional editing jobs through the years. She was also featured in documentaries including “Sisters in Cinema” (2003), about the history of African American female directors, and called on younger generations of filmmakers to hire more women and people of color.

“You can’t stop progress. You can hold it up for a minute, but you can’t stop it,” she told the Times, looking back on her career. “Some people have asked, aren’t you angry that you had to go through all that? And I said no, I made money, and I had fun. So why would I be angry? You don’t get anything unless you pay a price for it.”