For anyone with an eye on video game news, it’s been hard to ignore the recent rise of names like Annapurna Interactive, Devolver Digital, Private Division, Humble, Epic Games and Netflix tied to independent projects. The distribution process for indie developers has shifted over the past few years from a self-publishing-first model, to one that prioritizes deal-making and acquisitions. For the moment, this shift is powering a small but highly visible boom in the world of indie games.

“I don’t think I ever want to self-publish again.”

Ben Ruiz has been a game developer since 2005, and in that time, he’s pretty much done it all. He founded two studios, he did contract work on titles including Super Meat Boy and Overland, and he independently published a tentpole original project, the monochromatic brawler Aztez. Nowadays, Ruiz is running a five-person studio called Dinogod and he’s building Bounty Star, a game that blends mech combat with life-sim mechanics. Bounty Star is being published by Annapurna Interactive and it’s due out in early 2024.

Annapurna Interactive

“Everything favors a publisher relationship, seemingly, because self-publishing has become this extraordinarily difficult thing,” Ruiz said. “It’s possible, but without help, I just don’t know how anyone’s doing it … I got a lot of friends in the same boat.”

Ruiz’s career is a microcosm of the shifting landscape for indie developers over the past 10 years. He began working on Aztez in 2010, when Steam was a curated marketplace where Valve employees hand-selected individual games for the platform. This system had fully imploded by 2012: On the heels of breakout hits like Braid, Super Meat Boy and Fez, the indie market was overrun by new games and developers, and Steam dropped its curation efforts. It shifted to a community-voting approach called Greenlight, before eventually landing on the everything-goes Early Access model we know today.

Ruiz and his business partner built Aztez in between contract projects, and by the time it was ready to debut on Steam in 2017, the indie market was saturated. There were 309 games added to Steam in 2010; in 2017, there were 6,306. Even with a hefty amount of hype behind it, Aztez had trouble standing out, and that was the last time Ruiz tried self-publishing.

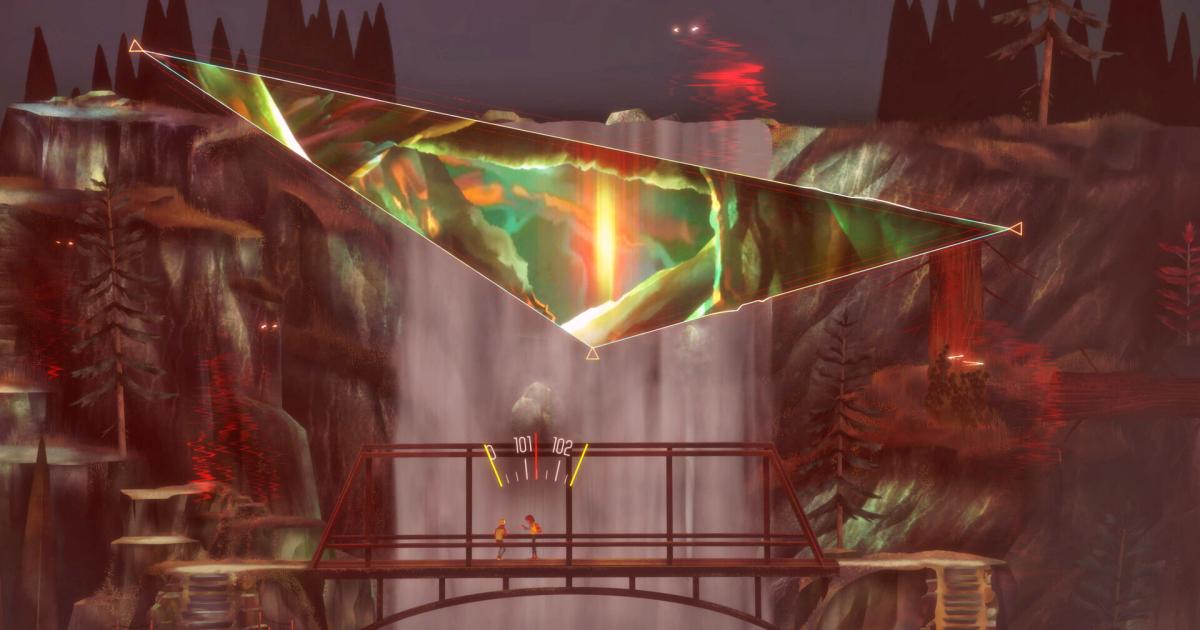

Ruiz did contract work for a while after Aztez, and in 2018 he pitched Bounty Star to people he knew at Annapurna. The game has a complex premise — it stars Clem, a desert bounty hunter with plenty of baggage, and it involves mech battles, emotional narrative scenes and home-management mechanics, including some light gardening. Annapurna bit, and Ruiz landed a publishing deal.

Annapurna Interactive

Annapurna Interactive is one of the most prominent publishers of indie games today, with titles like Stray, Outer Wilds, Neon White, Donut County and What Remains of Edith Finch on its books. It was founded in 2016 as an offshoot of Annapurna Pictures and quickly established its brand as an arthouse publisher, focused on visually innovative and emotionally driven experiences. Its showcases are now a staple of the gaming calendar.

Annapurna is handling the marketing for Bounty Star, and it’s also financially supporting Ruiz’s studio, Dinogod. When Ruiz pitched the game, he was clear that he’d need a team of five or six people to bring his vision to life, and Annapurna gave him the funding to hire up.

“The fact that Dinogod has five full time people, that was a part of the partnership,” Ruiz said. “When everything was greenlit, that was the first step, to bring in these five or six people…. If [Annapurna is] into a thing that they think is a good move, and it needs more people, that seems to be fully okay. Like, they’re not averse to scale.”

It’s not just Annapurna making these types of deals with indies nowadays. Devolver Digital is the granddaddy of indie publishers, and since 2009 it’s released hits including Hotline Miami, Hatoful Boyfriend, The Talos Principle, Gris, Fall Guys, Inscryption, Weird West and Cult of the Lamb, all in collaboration with small development teams. There’s also Humble, Private Division, Raw Fury, Epic Games, Finji, Gearbox, EA and Netflix, all of which have stepped up their indie publishing efforts in recent years. Meanwhile, Microsoft’s strategy is to simply acquire the studios it likes, and today it has 23 developers under the Xbox Game Studios banner. Sony is taking a similar approach, though it owns fewer studios than Microsoft. Microsoft and Sony are also signing hundreds of one-off deals with indies as they attempt to fill their streaming libraries — Xbox Game Pass and PlayStation Plus Premium — with a steady stream of new experiences.

This is the new standard for indie developers: Identify the publisher that best matches your game’s tone, pitch it, and pray. Even established studios, such as Device 6 creator Simogo, have swapped to a publisher-first model. Simogo’s latest projects, Sayonara Wild Hearts and Lorelei and the Laser Eyes, are the result of its partnership with Annapurna.

Annapurna Interactive

“I think for us as a studio, the biggest change is working with a publisher, something which we would see as completely uninteresting and impractical ten years ago,” Simogo co-founder Simor Flesser told Engadget earlier this month.

And then there’s Netflix. The streaming company officially entered the game-distribution business in 2021, and it’s on track to have 100 titles in its library by the end of 2023, all freely available to anyone with a Netflix subscription. It’s already brought a number of high-profile titles to mobile devices, including Kentucky Route Zero, Poinpy, Into the Breach, Spiritfarer, Lucky Luna and Oxenfree II, and it’s purchased a few studios outright — notably, Alphabear developer Spry Fox and Oxenfree house Night School Studio. The first of these purchases was Night School, which Netflix acquired in 2021.

“Consolidation — I didn’t really have my finger as much on the pulse of that, because when we joined Netflix, it didn’t feel like that was happening so rapidly,” Night School co-founder Sean Krankel told Engadget. “And now in the last few years, literally, it’s non-stop.”

The acquisition allowed Night School to move into the Netflix offices and it provided stability for the studio overall, Krankel said. With Netflix’s resources, the Night School team was able to add day-one support for 32 languages in Oxenfree II, and they were able to fly in remote collaborators as needed.

“All that’s really exciting,” Oxenfree II lead developer Bryant Cannon said just ahead of the game’s July 12th release. “I think the game is going to be better because we have this battery in our back.”

Netflix

Outside of acquisitions, Netflix is also signing individual deals with developers. Snowman is best known as the name behind Alto’s Adventure and Alto’s Odyssey, and its latest project is Laya’s Horizon, a serene wingsuit experience exclusive to Netflix. There are two big benefits of working with Netflix, according to Snowman creative director Jason Medeiros: The instant access to an audience of more than 230 million people, and the freedom to build a game without worrying about monetization.

“You’ll notice real quick that the game that you’ve been playing can’t be free-to-play,” Medeiros told Engadget in April. “Like, where would the ads go? It’s this fantasy world with no currency, even, and all that’s intentional. As the creative director, I didn’t want any of that stuff. Because I mean, I liked games before all that stuff happened. So having a platform like Netflix, it’s just like, none of that matters. You don’t have to do that stuff. It’s a breath of fresh air; we jump on opportunities to make games that way.”

Of course, there are still developers self-publishing their projects — Vampire Survivors, Phasmophobia, Celeste and Among Us are all standout examples — but there’s a murkier path to success with this model, one based on timing, trends and a hefty amount of luck. There are more than 90,000 games on Steam today; Xbox Game Pass and PS Plus Premium libraries each have more than 400 titles (and counting). In this marketplace, it’s hard to stand out without a little help.

It’s taken 10 years to get here, but it’s now a solid, quantifiable fact: There’s a lot of money in indie games. So much money that outside companies are popping up and trying to get a piece of the pie — and for now, it’s created a shiny bubble of pretty PR packages and bespoke showcases dedicated to small teams and their games.

Devolver Digital

It’s difficult to ignore the potential for exploitation down the line, especially with Netflix in the mix. Amid the ongoing writers’ and actors’ strike, the company is facing accusations that it instituted wildly unfair compensation deals for creatives, paying out one-time, minimal wages even as projects became massive hits on the streaming service. Annapurna, for its part, was accused of mishandling claims of abuse at three prominent studios on its publishing roster — Mountains, Funomena and Fullbright — in a March 2022 documentary by People Make Games. Meanwhile, the current consolidation craze is shrinking the video game industry overall, even as the market caps of the biggest companies continue to rise.

For now, bespoke publishing is the name of the indie game. This system has already distributed innovative and important games to huge audiences — Tchia, Tunic, Sea of Solitude, Gris — and it’s offered stability to a lot of independent artists. Like, for instance, Ben Ruiz.

“I hope Annapurna’s success means more Annapurnas in the future,” Ruiz said. “It doesn’t feel like they’re just trying to grab a thing that will make money or collaborate with people that are just going to make them money. They clearly have a brand and an aesthetic directive … if I can keep making games for them for a long time, I will.”

The new normal works for Ruiz — and Flesser, Krankel, Medeiros and plenty of others. For now, it’s a functional system, even if it ultimately leaves publishers, rather than independent developers, with most of the power.