Until I was thirty-three, I thought I knew everything important about the life my mother, Pearl Kazin Bell, had lived before I was born. She often told me about it: her desperately poor childhood in a Jewish immigrant family in Brooklyn; her years at Brooklyn College and then, briefly, in an English graduate program at Harvard; her jobs at various magazines in New York City, including Harper’s Bazaar and The New Yorker. I knew she had had a brief, unhappy first marriage to a photographer named Victor Kraft, with whom she had moved to Brazil for a time. I knew she had written fiction and published a lovely story in The New Yorker about the first time her family celebrated Thanksgiving. I knew that she had been friends with famous writers: Truman Capote, Elizabeth Bishop, Saul Bellow. I knew that she had traveled widely, and lived for several months with Capote in a ramshackle house in Taormina, Sicily.

I was all the more confident that I knew about her earlier life because so much about it had appeared in print. Her older brother, the writer Alfred Kazin, had made his reputation in large part with memoirs about his childhood—their childhood—and about New York’s midcentury literary and intellectual milieu. Alfred had been an important member of the group known as the “New York Jewish intellectuals,” which also included my father, the sociologist Daniel Bell, whom my mother married in 1960. By the 1980s interest in the group had generated a small academic cottage industry. Books on it appeared at regular intervals.

I read these books with fascination, even as my father expounded dyspeptically on what he saw as their faults and misrepresentations. At the time it did not occur to me that they—and Alfred’s memoirs—expressed an almost entirely male perspective, that the experience of a woman in this world might have differed enormously. I also failed to think much about how, in our small family, my father had dominated conversations about both his and my mother’s pasts, often imposing his point of view on her stories.

Above all I assumed I knew about her past because I knew her. I was her only child; I knew her friends; I knew her work as a book critic for prominent magazines. I thought I understood her often difficult relationship with my father. I knew the things she cared about most: family, friends, English literature, and the English language. Although generally an indulgent, even overprotective parent, she deeply disapproved when I said “like,” “you know,” or “stuff,” and even when I used “hopefully” incorrectly—not as an adverb but to mean “it is hoped.”

One day in December 1994 I discovered just how little I really knew. A colleague at the university where I taught casually mentioned that I might want to look at a newly published collection of Elizabeth Bishop’s letters. Your mother is in there a lot, he said. The next day I found the book and there she was in the index, with a large number of entries: “Kazin, Pearl.” I went to one at random. It was a letter from October 1950, from Bishop to the painter Loren MacIver. In the middle of a long paragraph of gossip were these eight words: “Pearl & Dylan, the talk of the town.” Dylan was the poet Dylan Thomas.

That evening I called my mother to ask if it was true. She was then seventy-two, in good health and spirits, and eagerly awaiting the birth of her first grandchild, my daughter, the next spring. But the question clearly took her aback, and she responded in a curiously flat, matter-of-fact tone. Yes, she had been involved with Dylan Thomas. The affair had been short-lived, as she had not wanted to break up the poet’s marriage. She added, with a slight nervous laugh, that Thomas’s wife, Caitlin, had sent her a letter that began “Dear Lower-than-the Dust.” But then she quickly changed the subject. I sensed pain in her voice, and, for the moment, didn’t press her further.

Over the next few years, as my wife and I brought two children into the world and worked to get tenure, I usually felt too overwhelmed to think about how I might ask her more about the relationship, or about other aspects of her previous life that she had not revealed. And then, in 2002, tragedy struck: my mother slipped and fell on steep stairs at a friend’s house and hit her head hard enough to sustain serious brain damage. When she came out of a coma, weeks later, she could no longer speak coherently, or walk, or use one arm. A woman who had taken such pride in her command of the language could now only produce broken shards of sentences. Whatever memories and stories she might have shared were shut away forever. She lived for another nine years, but by the end had slipped into almost complete silence, save for the occasional, dreadful moan. Seeing her in this terrible state, the questions about her early years didn’t seem to matter.

But after her death they returned. In going through her things, I found a volume of Yeats’s poetry inscribed, in Dylan Thomas’s handwriting:

Pearl

Dylan

London

September

1950

love

A few months later, one of her closest friends, Bede Hofstadter White (widow of the historian Richard Hofstadter), sent me a thick pile of letters that my mother had written her in the 1950s. They were wonderful: witty, lushly descriptive, frank, and personal. Then, in 2012, a Welsh bookseller and Dylan Thomas admirer named Jeff Towns contacted me with the news that he had purchased, and planned to publish, a set of letters the poet had written to my mother. He enclosed copies, which were extraordinary. “Every moment of every day I think of you. I feel you, I want you,” Thomas had written to her in August 1950.

I talk to you silent and alone. My very dear Pearl, my love.… Even when I read, again and again, your most loving letters…I was still shy as a badger when it came to putting down, to sealing in an envelope, to sending over the fishy sea “I love you.” But now I have said it, I can again and again (I love you, Pearl) and I wonder how under the sun I couldn’t have said, a hundred times over, such a simple, enormous, and deeper than the Atlantic truth.

In 1973, for reasons I have never been able to uncover, my mother sold these letters to a rare book dealer.1

For years I wondered whether I should carry out a more comprehensive investigation into her early life. I am a historian, with ample experience working in archives and piecing together stories from fragmentary sources. In addition, on the hundredth anniversary of my father’s birth, in 2019, I published a short memoir about him and wondered if it was unfair not to write about my mother as well. But prying into material that she had not wanted to share with me felt like a violation of her privacy, and I hesitated.

The same year, however, a young historian named Ronnie A. Grinberg contacted me in connection with a book she was writing on gender and the New York Jewish intellectuals, and I did an extensive interview with her (the book itself is appearing this year).2 Other books on the milieus my mother had belonged to, and the people she had known, were continuing to appear at a regular pace. It became clear that my mother was going to be written about. And if so, I wanted to have my own vision of her on record.

So I began serious research. I went back to the two short memoirs my mother herself had written, one about Elizabeth Bishop and one about her time at Harvard. I hunted down every reference I could find in published works, combed through unpublished diaries and letters in several archives, and thought back as intensely as possible (although acutely aware of the tricks memory can play) to the stories she had told me herself. “Letters, of course” my mother wrote in one of those memoirs, “are dark dots on paper: one does sometimes yearn for the voice to bring them to life, or at least to enfold them in memory.”

What I found often saddened me. In the 1940s and 1950s my mother experienced more than her share of frustration. She was taken advantage of, belittled, even betrayed. She confronted obstacles that her male counterparts did not. She battled against what she called, in a painful letter to Bede, the “shadowy side of the psyche.” She never fulfilled her ambition of becoming a successful fiction writer. But the research also filled me with admiration. I discovered that, despite the disappointments, she had led a courageous life—a life of freedom and desire.

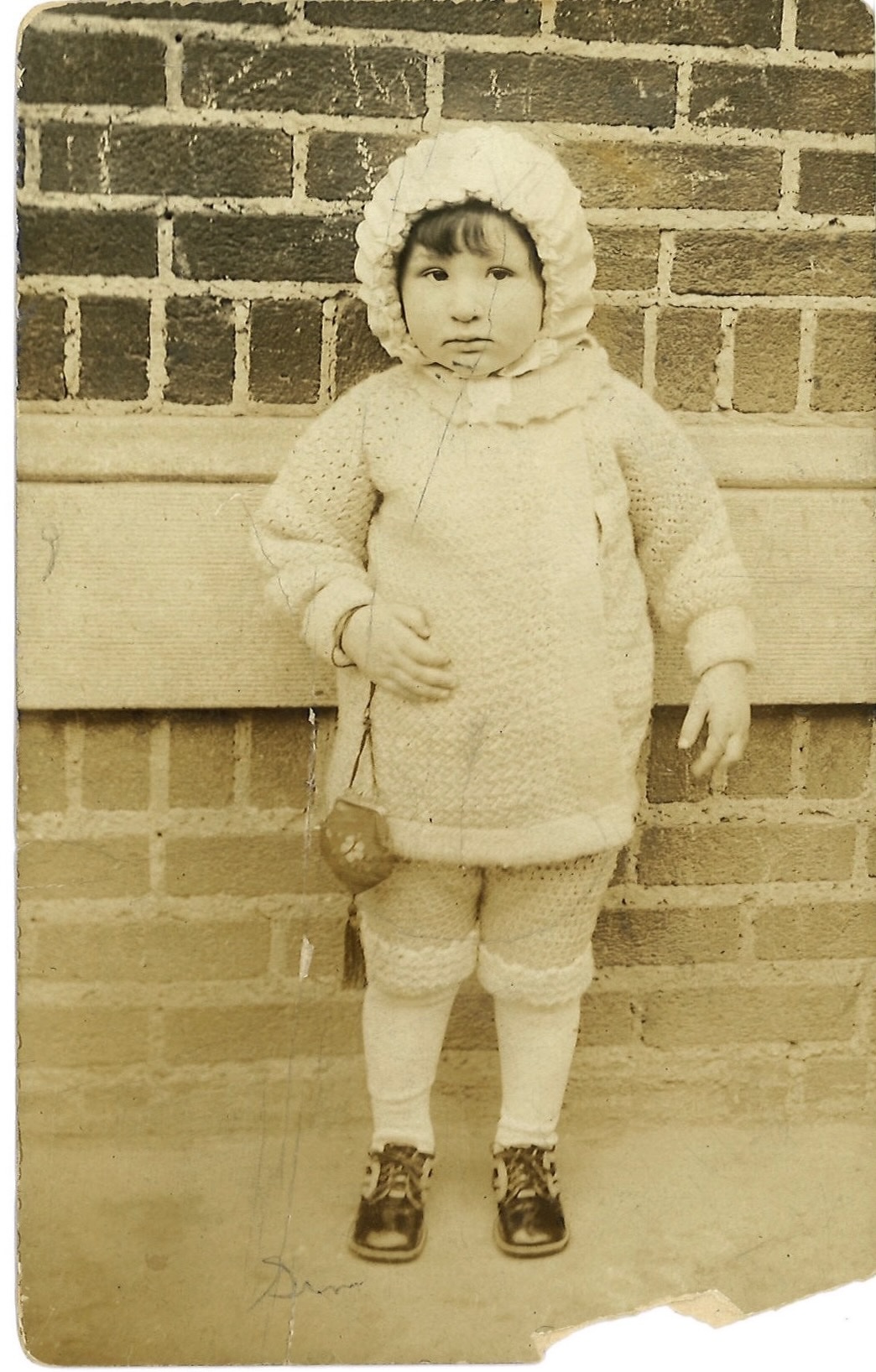

A reader of Alfred Kazin’s memoirs A Walker in the City and Starting Out in the Thirties would not know that he had a sister. He wrote eloquently about their shy, quiet father, a precariously employed house painter, and their emotionally domineering mother, who kept the family barely afloat during the Depression as a seamstress, glued day and night to her pedal-powered Singer sewing machine. He provided lush descriptions of the Yiddish-speaking Jewish ghetto of Brownsville, Brooklyn, and of his own desire to escape. As he put it, Brownsville was “a place that measured all success by our skill in getting away from it.” But my mother’s name does not appear once in either book.

Yet if she seems to have failed to register in his life, he registered hugely in hers. Seven years her senior, strikingly handsome, and brilliantly successful in school, he was, she told me many times, the greatest single influence on her as a girl. He did not hesitate to instruct her on how to act, and, even more importantly, what to read. Her passionate love of language and literature started with him. There was never any question but that, when she entered Brooklyn College at sixteen, in 1938, she would major in English.

Alfred’s precocious success also opened opportunities for her. At twenty, he was already contributing book reviews to The New York Times and The New Republic. At twenty-seven, in 1942, he published the book that established him as one of the country’s foremost literary critics: a sweeping survey of American prose fiction called On Native Grounds. My mother was still just twenty, but through Alfred she met leading editors and critics and exciting young writers.

Alfred was an easy person for a younger sister to worship, but he was also an easy one to resent. To start with, Jewish Brownsville did not exactly treat boys and girls equally. My overbearing grandmother directed the floods of her hope and anxious attention almost entirely toward her glittering son. In a 1957 letter to Bede Hofstadter, my mother recalled how early the imbalance became obvious to her. “My memories of Alfred’s bar mitzvah have always been clear as London churchbells on Sunday,” she wrote. “It took about four days to do the strudel alone, and when I saw all those fountain-pens rolling in, I thought it was damned unfair that I’d never be in line for all that loot.” (At my grandparents’ synagogue there was no such thing as a bat mitzvah.) As for Alfred himself, he quickly lost interest in his much younger sister, whom he cruelly described in his private journal as self-absorbed and “pathetic.”

Nor was the New York intellectual world itself anything like an easy place for her—for any woman. Diana Trilling later recalled: “Unless a man in the intellectual community was bent on sexual conquest he was never interested in women.” Ronnie A. Grinberg, in her forthcoming book, argues that the mostly male New York Jewish intellectuals tended to cultivate a self-consciously macho pose, in part as a reaction to gentile views of Jews as weak. A few women, including Trilling, managed eventually to gain footholds among them. But they generally did so by what the editor Jason Epstein called writing “like a man,” and by developing tough, aggressive personae (I still remember Diana from my childhood as by far the most intimidating of my parents’ friends). This was not an option for the young Pearl Kazin. If Alfred, in his personality, took after their mother, she inherited something of their father’s reticence and reserve. In the Elizabeth Bishop archives at Vassar I found a letter to her in which Bishop wrote: “I have always suspected that you are the type that gives too much, Pearl—you are probably just too kind and generous with the opposite sex, who do tend to be selfish brutes, after all.”

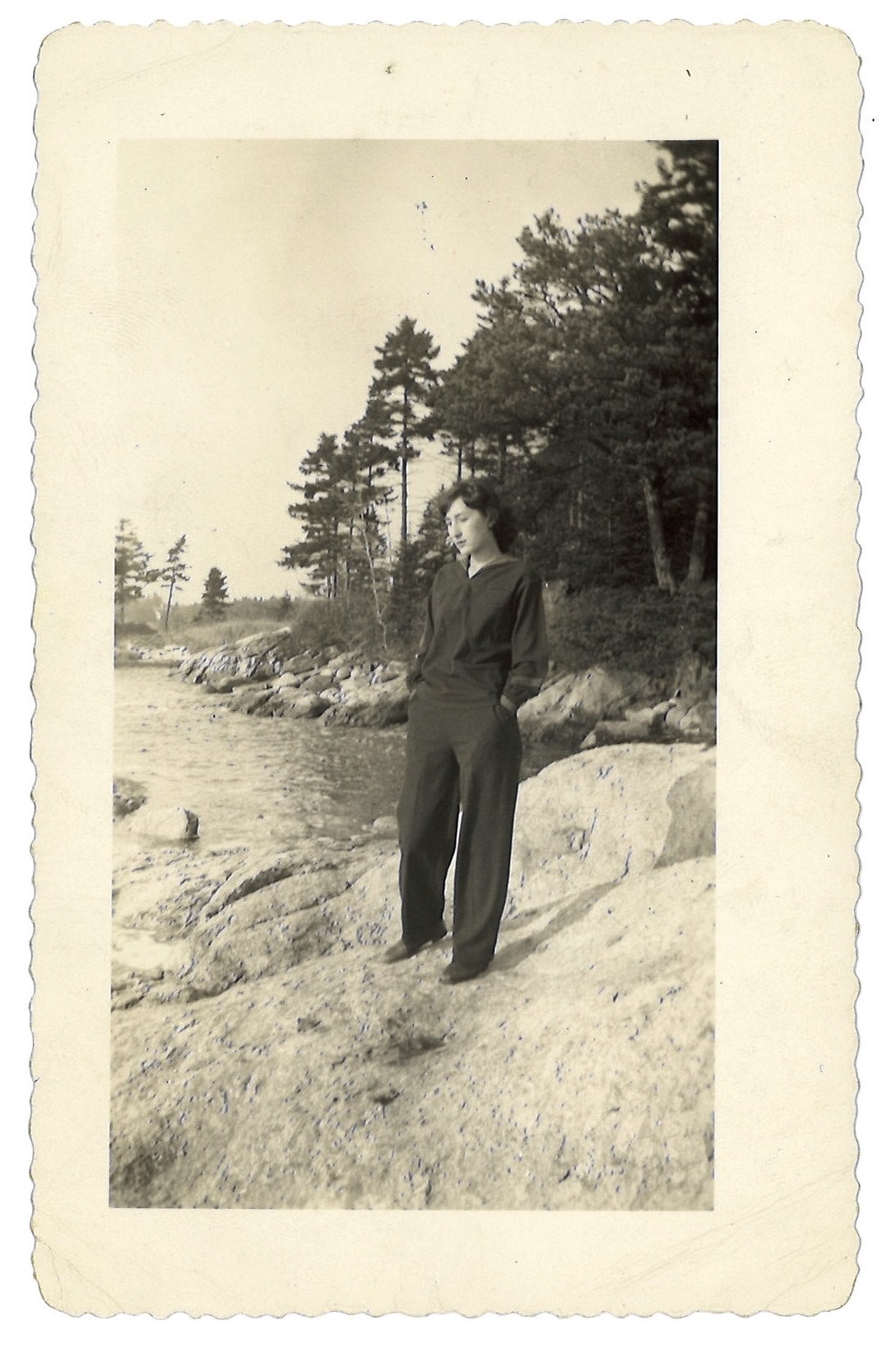

She did not, however, accept discrimination as her lot. Instead she sought her own forms of escape: from New York, from the macho environment of its young Jewish writers, and from her brother’s shadow. In 1943 she won a fellowship to graduate school in English at Harvard. She had little love for the traditional graduate curriculum, which was still highly philological, requiring courses in Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse. But she adored the faculty, to whom she had unusual access, since so many male students had gone off to the war. “Professor Magoun,” she wrote in her short memoir of her time in Cambridge,

introduced us to the beauty and sadness of Anglo-Saxon lyrics and the melodrama of Beowulf. So intense was the emotion aroused by Magoun’s lectures…that years later, in a small boat crossing the Königsee in southern Germany, I felt that Magoun must have arranged the setting of mysterious white mists blowing along the shore.

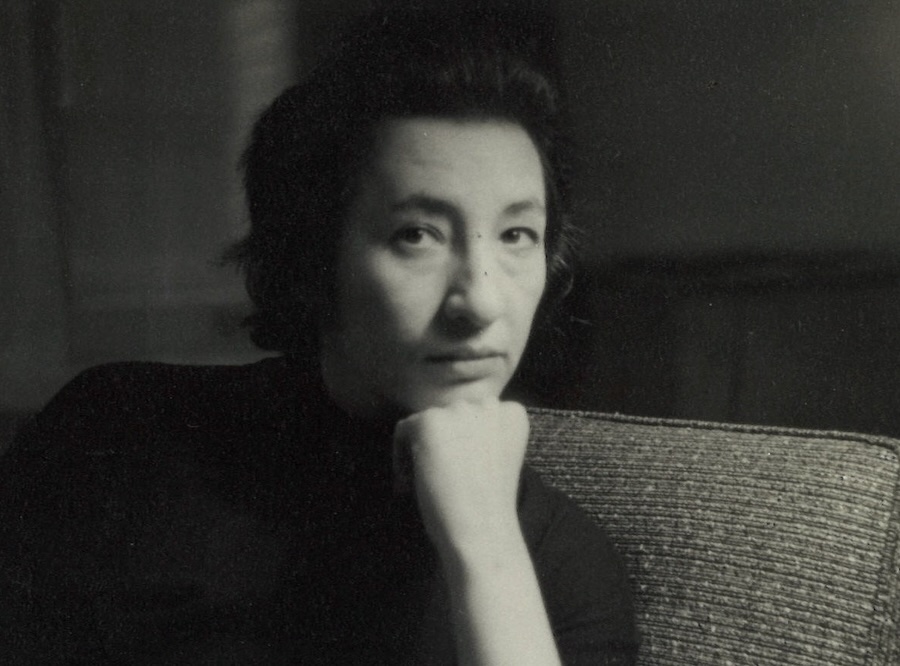

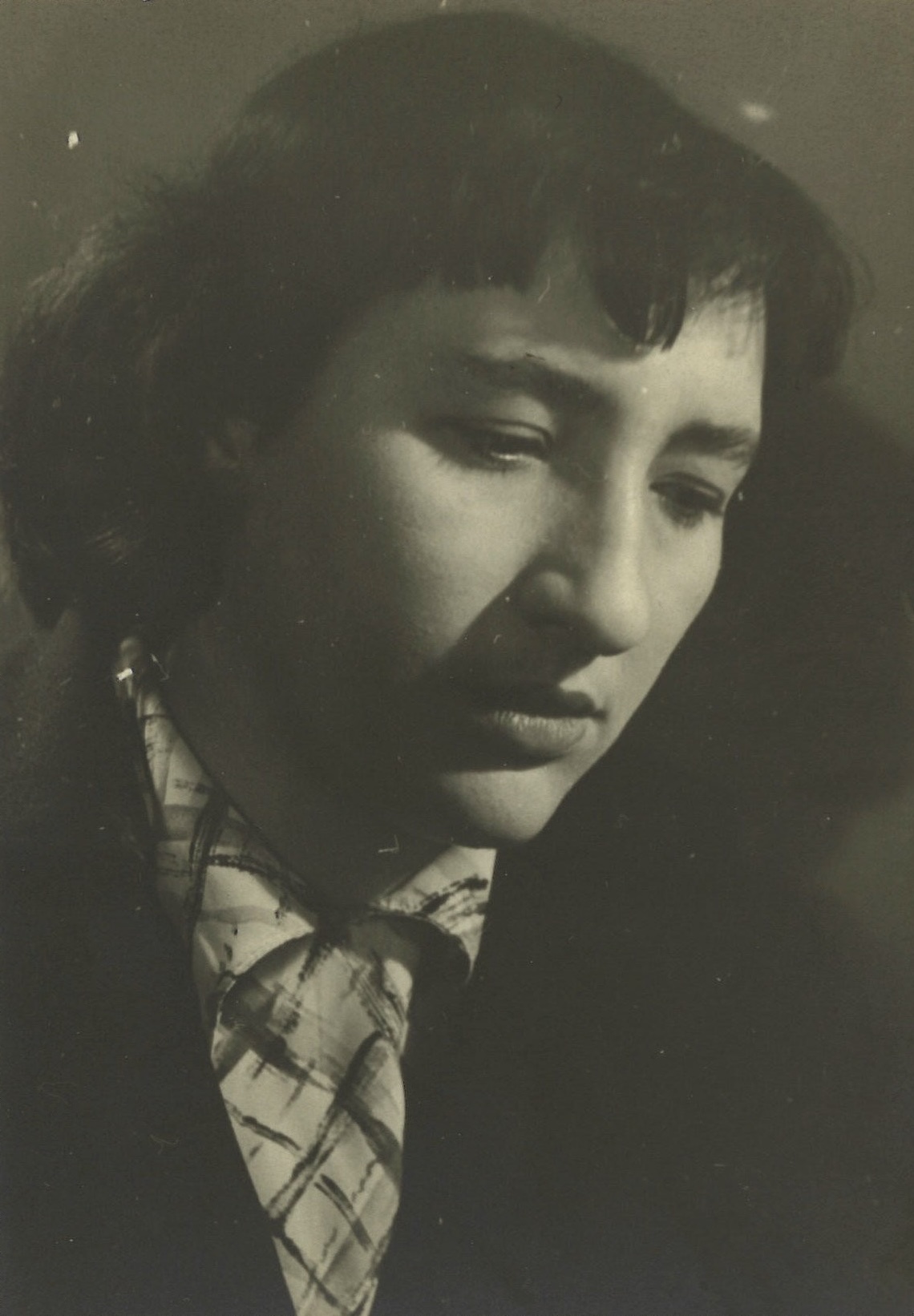

One of my favorite photographs of my mother shows her striding across Harvard Yard with a happy, determined expression. She was thin, tall for a woman of her generation, with dark, striking features that closely resembled Alfred’s.

The years at Harvard left other marks. Her strong Brooklyn accent, she told me once, when I was a teenager, seemed to physically repel the other students and faculty. So she took elocution lessons and lost it. When I asked her to say something in her old accent, she spoke a few sentences in the broadest Brooklyn I had ever heard. Without thinking, I gasped, “Oh my God,” and a look of horror and shame crossed her face.

When I was a boy, at home my father would sometimes lapse into Yiddish, the language both my parents had spoken before starting school, but my mother almost never did. She never openly expressed any shame about the immigrant world she came from, but the genteel and reserved way she spoke, dressed, and carried herself—perfect posture, no hand motions, skirts and sweaters in muted colors—made clear that she had left that world behind forever.

One Harvard professor made a particular impression on her. Francis Otto Matthiessen was one of the period’s great scholars of American literature and had written sensitively about female authors such as Sarah Orne Jewett. He was also a closeted gay man, who took my mother much more seriously than Alfred’s male friends in New York had. She worked for him as a “section man” (women went by the title as well), and they grew close. In her memoir, she recalled an incident in which he exploded at male students who had giggled during his discussion of sexual themes in the works of Eugene O’Neill. “I raced after him to his office in Grays 18, where I found him moaning, ‘How could I have let myself go that way?’”

My mother did not stay long in Cambridge, having realized early on that a Jewish woman had little chance of landing a tenure-track position. She also hoped to snag a publishing job before returning military men flooded the market. In 1945 she returned to New York, and soon she got her big break: a position as assistant fiction editor at Harper’s Bazaar under Mary Louise Aswell, a thin, elegant, nervous woman twenty years my mother’s senior, who became a lifelong friend and my godmother. During my childhood, my mother frequently took me on visits to “Mary Lou” in Santa Fe, where she had retired with her partner Agnes Sims. She relaxed with them as she rarely did with my father, breaking out of her reserve and laughing uproariously.

In the 1940s Harper’s Bazaar, while principally a fashion magazine, occupied an unusual niche in the world of American letters. The New Yorker, under its longtime editor Harold Ross, was still mostly avoiding fiction that might strike readers as overly daring or difficult, leaving an opening that Mary Lou rushed to fill. She published important young writers, including Capote and Bernard Malamud, and nurtured their careers. It was the perfect place for my mother, and she quickly became part of the literary circle around the magazine. Already in August 1946, Capote was writing to Mary Lou: “I had a drink with Pearl Kazin the other day, and she is a dear person, and fantastically bright, much brighter, I think, than her brother, whose work I find very aggravating.” They became warm friends. In letters, he called her “my own precious Pearlie.”

Not every writer appreciated the magazine’s “high” literary standards. In 1947 my mother had invited a young war veteran named Norman Mailer to submit a story. “She irritated the hell out of me,” Mailer reported in a letter to a friend. “She was so super-superior. She read more books; she was more on top of things.” In his carefully cultivated crude style he replied: “Dear Pearl Kazin, I’m still too young and too arrogant to care to write the kind of high-grade horseshit you print in Harper’s Bazaar.”

Two years later my mother was awarded a monthlong residency at the Yaddo writer’s retreat in Saratoga Springs, where she soon met another fellow: Elizabeth Bishop, eleven years her senior. My mother introduced herself and the two started spending time together, wandering the town and going to the Saratoga horse races. Bishop, my mother later remembered, came alive when she had a spectacle like the track to observe:

Her tireless eye…responded to every detail…the crowds swarming in the heat of the day; the tense expectation, palpable as heartbeats, as the horses pounded around the track…. Elizabeth’s attention was absolute, and even when she was silent I was intensely aware of the way she was capturing the roiling motion of the afternoon.

But Bishop also fell into depression and drank heavily: “She seemed assaulted by nameless demons that couldn’t be disarmed.”

In 1951, when Bishop arrived in Rio de Janeiro, my mother was already living there and showed her around, the two women “shuddering our way through the dodg’em buffalo stampede of downtown traffic.” In Rio, Bishop fell in love with a Brazilian architect named Lota de Macedo Soares; she ended up staying in the country for more than fifteen years. Although my mother returned to the US much sooner, the two exchanged hundreds of letters until Bishop’s death in 1979. My mother sent Bishop so many consumer items from the United States, everything from girdles to marmalade, that Bishop jokingly called her “Our Lady of the Personal Shopping Service.”

Bishop and Mary Lou were two of the many gay men and women toward whom my mother gravitated. In 1947 the gay book editor Leo Lerman, who belonged to the circle around Harper’s Bazaar (and who called my mother “the cultured Pearl”), wrote in his journal that “Pearl is so bright and feminist and desperate to remove the yoke of Alfred, she occupies herself with queer boys, where she can feel dominant. This is a typical American female character.” Lerman’s private assessments of even his close friends tended toward the cynical, and I am sure that, in comparison to overbearingly macho characters like Mailer (and Alfred), my mother found the “queer boys” a relief.

Harper’s Bazaar’s reputation, and the high fees it paid for fiction, made it an obvious place for Dylan Thomas to visit in May 1950. Thirty-five years old, already one of the world’s best-known poets, enormously handsome and charming, and severely alcoholic, he had come to the US on a tour arranged by my mother’s young gay friend John Malcolm Brinnin. Thomas hoped to sell a story about his childhood, which my mother bought and gave the title “A Child’s Memories of a Christmas in Wales” (later shortened to “A Child’s Christmas in Wales”). Within days of meeting, they were lovers.

The affair was never a secret, but it is also hard to piece together, and Thomas’s biographers have never gotten it entirely right. The most important source is Dylan Thomas in America, a memoir that Brinnin published in 1955, two years after Thomas’s death. My mother read much of the book in draft, gave Brinnin suggestions, and praised the final version. In the published text he changed her name to Sarah and altered many other details. He also described her as an important editor with an elite education and an “air of professional sophistication.” My mother certainly tried to present herself this way, but she was still a Jewish woman not so far removed from a poor immigrant background, and prey to enormous insecurities.

At the start, it is doubtful that the relationship meant very much at all to Thomas, who had a wife and three children and was notorious for his philandering. During his brief stay in New York, he carried on simultaneous affairs with my mother and Jeanne Gordon, the wife of a psychiatrist. My mother, though, was clearly overwhelmed. In Dylan Thomas in America, Brinnin described the end of Thomas’s trip in these terms: “As the ship began to move away, I noticed Sarah standing quite by herself far away from me, quietly weeping. When she ran toward me, we embraced in an absurd and wordless flood of tears.”

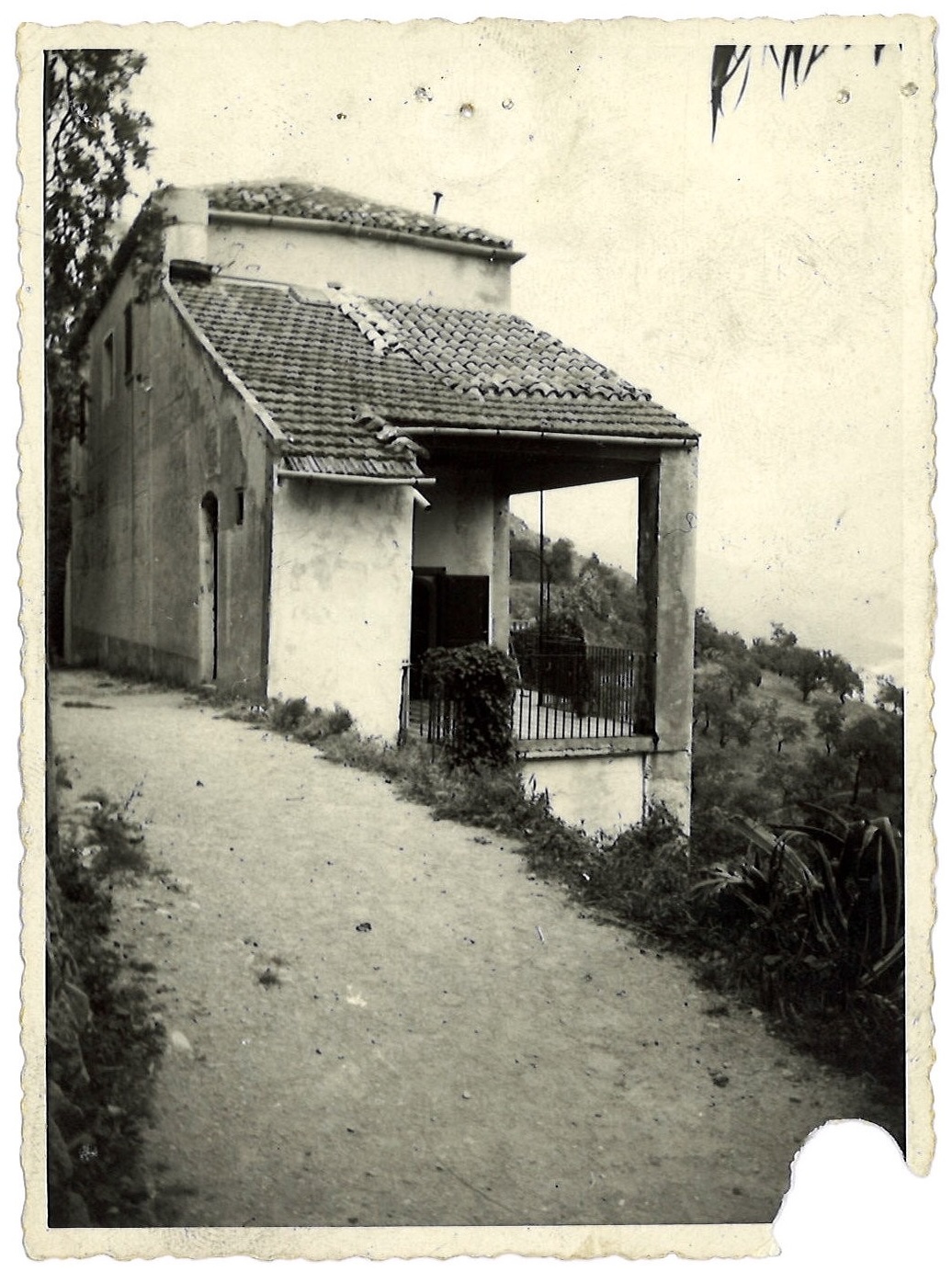

But it was not the end of the romance. My mother and Thomas corresponded, and in the process his feelings seemed to strengthen. Before long they were making plans to meet again. Truman Capote had temporarily absconded from McCarthyite America to Taormina, Sicily (Brinnin changed it to Greece), and invited my mother to visit him there, giving her an excuse to travel to Europe. Already in June 1950, Thomas was writing with excitement about her visit: “I would meet you, gardenia in buttonhole, with a gold hat, dancing and leering, at Southampton or London. Wherever you come, I shall meet you…. The world is empty this side of the damned sea.”

On September 4 she arrived in London on a converted freighter and immediately met up with Thomas. He took her off to a hotel in Brighton and then, back in London, on a tour of his favorite pubs, not caring who saw them together. An acquaintance of his later confirmed this account, noting that “he was with the Kazan [sic] girl and I thought they seemed much in love.” Brinnin, who was in England when my mother arrived, claimed that at one point Thomas drew him aside and asked: “John, what am I going to do?… I’m in love with Sarah and I’m in love with my wife. I don’t know what to do.” Many years later, Caitlin Thomas confirmed in an interview that “he obviously was pretty serious about her.”

But the affair soon hit an obstacle. My mother left for France to visit a friend, and during her absence Caitlin discovered the affair and felt, in her words, “absolutely mad with rage.” She then wrote the letter my mother told me about in 1994. Thomas, meanwhile, fell ill with pleurisy and then pneumonia, and asked one of his patrons—Margaret Taylor, wife of a prominent historian—to fetch his correspondence at his club, where he had asked my mother to write him. Taylor did so, but rather than delivering my mother’s letters from France she destroyed them, undoubtedly to protect Thomas from a woman she saw as unsuitable, at a time when divorce still carried a heavy stigma in Britain. My mother only discovered the truth later, calling what had happened (in a letter to Brinnin) a “lurid Jacobean-drama saga” and describing Taylor coming to see her “laden with her flowers and dulcet doom.” Despondent, she left for Sicily, where she wrote to Brinnin to thank him for sending snapshots he had taken of her and Thomas. “But that’s the end of it now,” she added, “with all its soap-opera bubbles broken, finally.”

My mother ended up staying for three months with Capote, who wrote to a friend: “I think she is unhappy over her bust-up with Dylan T.” She loved the “tranquil beauty” of Taormina, and at one point wrote to Brinnin that “the days continue to be wonderfully happy here, filled with peace and work and the sea.” But a letter from Capote to a friend, complaining that she had overstayed her welcome, hints at darker feelings: “Pearl is still here. She is not, alas, the most stimulating girl alive.” Even so, after she had left, Capote wrote her several letters insisting how much he missed her and asking her to come back soon. On one, his companion Jack Dunphy drew a cartoon of their dog, Kelly, asking “Where’s Pearl?”

During her time in Sicily my mother also wrote her first published story, “The Jester,” for the international literary magazine Botteghe Oscure. It was a highly mannered and rather cruelly comic account of the death of an obese New York literary figure, clearly based at least in part on Leo Lerman, to whom my mother, having heard of the way he gossiped about her, had now taken a deep dislike. “Surely he was one of the most sexless people I have ever known,” she wrote in the story, “not only because his grossness would seem to negate it for him, but one never thought of Kuney as needing sex.” It is hard not to read the story as an outlet for the tumultuous emotions she was feeling at the time. Capote quipped in a letter to a friend that it “would take the skin off an elephant.”

But she could not put the romance behind her. Soon after returning to New York in early 1951, she received a new letter from Thomas. “Though thousands of miles apart, we are still together,” he wrote. “Forget that cancerous woman [Margaret Taylor] and, if we can, all the dumb dark that lay between us for so long.” What happened next strongly suggests the depths of her continuing turmoil. Through Harper’s Bazaar, she had become friendly with Victor Kraft—the photographer and darkly handsome companion of Aaron Copland who also counted Leonard Bernstein among his lovers. Capote’s letters reveal that Kraft had called to console her in Sicily. In July 1951, to the shock of her friends and family, the two announced their engagement. Moreover, Kraft had taken a job with a Brazilian newsmagazine; it was in order to be with him that she flew to Rio de Janeiro two months later.

When I was growing up, my mother portrayed her time in Brazil to me as an adventure. She traveled through the country by bus, at one point meeting descendants of American slaveowners who had moved there after the defeat of the Confederacy, and who still spoke English in an almost incomprehensibly thick southern accent. But in her memoir of Elizabeth Bishop, she commented mostly on “the suffocating heat, the bad food, the untamable ants parading incessantly through our kitchen.” In a letter to Brinnin soon after her arrival in Rio, she praised the city’s natural beauty but added: “there’s no center to the place, and once the lovely visual shock has turned into the habit of context, one (me) is up against the brutalizing effects of inflation…. I hope we can clear out of here before too long.”

It was also already apparent that the impulsive marriage had been a mistake. Kraft emerges in biographies of Copland as a deeply troubled man who could never come entirely to terms with his sexuality. In the same letter to Brinnin, my mother said she wished she were back in Sicily and spoke of “the frenzy of accustoming myself to this strange new life, to the changes, both fine and difficult, which marriage makes necessary.” Soon afterward the couple separated, and my mother returned to New York. But in the 1950s it was difficult and expensive to obtain a divorce, and Kraft was peevishly reluctant to grant one. The two remained legally married until 1955.

The return home was not easy. “The Jester” had appeared, and its savage portrait of a man who closely resembled Lerman did more to alienate friends than build my mother’s reputation. Capote, who had originally praised the story, told my mother that he had written Lerman a “soothing note,” and said he would recommend it to a French magazine for translation. But at the same time he wrote to another friend about “the really ghastly bad story…. Leo has vowed to drive her from New York, and according to Pearl he has so far prevented her from getting two jobs.” He continued, cattily: “Myself, I have no side. I think they both are quite, quite expendable.” He then distanced himself from her, much to her distress. Still, he did not entirely cut her off. When she had been in Sicily in early 1951, she wrote to Brinnin: “T dreamed the other night that we were buying postcards in Russia….” The last piece of correspondence between them in Capote’s papers in the New York Public Library is a 1956 postcard he sent her from Moscow.

Back in New York, Harper’s Bazaar had replaced her, and instead she found a job as a copyeditor at The New Yorker. It paid well, and Bishop tried to cheer her up with a comic letter: “I sort of see you surrounded with fine-tooth combs, sandpaper, nail files, pots of varnish, etc.—with heaps of used commas and semicolons handy, and little useless phrases taken out of their contexts and dying all over the floor.” But despite the chance to write the occasional unsigned “Talk of the Town” piece, the job was a comedown from Harper’s Bazaar. Four years later she would complain to a friend about a “dictionary-grubbing…job that has been even more detestable to me than I’ve dared admit to anyone but Nell [her therapist].”

And she could not get over Thomas, who was now coming frequently to the United States and assuming he could continue their relationship. The ubiquitous Brinnin, in his book, described a 1953 cocktail reception in Boston:

Dylan and Sarah moved about as an intimate twosome and…a good part of conversation at the party was inquisitive gossip about them. When in the morning I drove him to the airport to catch a ten o’clock plane, he said he had stayed with Sarah in the apartment of a Cambridge acquaintance.

Yet by then Thomas, greedily impulsive as ever, was also conducting a serious affair with a woman named Elizabeth Reitell.

In November 1953 Thomas came to New York for the last time, drinking even more heavily (he claimed to have downed eighteen whiskies in a single sitting) and suffering from pneumonia and emphysema. In early November news came that Thomas had been taken to St. Vincent’s Hospital in a coma. On the evening of November 8 my mother was at a conference at Bard College with Ralph Ellison, who drove her and the poet John Berryman back down to the city. She and Berryman went straight to the hospital, and Ellison later remembered their “intensely private” grief. A nurse let them briefly into Thomas’s room, where he was lying under an oxygen tent. The next day he died, aged thirty-nine. A week later Bishop wrote to my mother: “Oh Pearl, it is so tragic. I hope you are not too upset by it, by whatever did happen to him…. Please, Pearl, tell me what happened to the poor man, if you know—and can bear to.”

Eventually my mother started dating other men, including, briefly, my father, although they would not come together for good until 1960. In some ways he was very much like Alfred: an ambitious, hard-driving Jewish intellectual from a poor immigrant family. One of his attractions, my mother later joked, was the fact that that he and Alfred cordially detested each other.

In 1955 The New Yorker published a story she had written, based on an incident from her childhood, about winning a Thanksgiving turkey at a raffle in a movie theater and finally persuading her immigrant mother to celebrate this most American of holidays. It captured the language of Jewish Brooklyn and concluded with a comic touch. Faced with the challenge of schlepping a large, live turkey home from the theater, my grandmother supposedly took a piece of clothesline from her purse and fashioned a leash. “What’s the matter, the turkey it hasn’t got legs, it can’t walk?… You have some better ideas, my intelligent daughter?” The story got considerable notice and gave my mother hope that she might finally have a real literary career.

So in the summer of 1956, she decided to strike out from New York again, to write. She traveled to the southern coast of Spain, where, with the help of an expatriate friend, she rented a small villa for $35 a month and hired a maid to clean and cook for just $6 a month. Initially she could not believe her good fortune: “It’s so glorious to wake up to bright light, dark mountains, blue sea every day,” she wrote to Mary Lou. She worked on stories and a novel, happy to be free of the drudgery of copyediting. “I’ve never worked harder in my life than I’m doing now, and…never been so generally content and cheerful,” despite “the lack of certain kinds of love.”

But the euphoria didn’t last. She found most of her expatriate neighbors irritating, and loneliness gradually crept up on her. Worse, The New Yorker rejected a story, and the money she had saved started to run short. In March 1957 she moved to London, hoping to find a more congenial atmosphere, but it didn’t work. The next month she wrote to Bede Hofstadter, conceding a kind of defeat:

I’ve been subjected to some rather fierce depressions in the last few weeks, because both time and money seemed to be running out so fast, and I think that if I’m going to stand up against the shadowy side of the psyche and outstare it successfully, I can do it better on my own home ground.

I never found the stories she worked on in Spain and London—she may well have destroyed them.

In June 1957 she returned to New York yet again. She resumed copyediting at The New Yorker and had new romantic involvements—including, she once told me, a young Canadian Jewish actor named William Shatner. In December 1960 she married my father (in Alfred’s apartment), and a few months later, somewhat unexpectedly, she found herself pregnant. I was born in November 1961.

For two decades my mother had lived freely and adventurously. But now, at thirty-nine, she fell into the life of faculty wife and mother, her days revolving almost entirely around her son and husband. In a memoir from 2003, Alfred’s ex-wife Ann Birstein wrote that after my birth my mother changed beyond recognition, becoming “an island surrounded by baby,” and breaking up lively parties when they disturbed the infant me. “Did Pearl ever mind being plunged back into a pure shtetl existence?” Ann continued, with more than a little exaggeration (and callousness, since my mother was no longer in a condition to respond). “I miss the old Pearlie, who was such a pal and had such fabulous lovers and got drunk at parties.”

I never once felt, growing up, that my mother resented me for how my arrival had changed her life. But she certainly resented my father, who expected her to drop whatever she was doing whenever he needed something. She often recalled the moment when she was teaching a freshman composition course at Columbia in the late 1960s and my father had a secretary call her out of class to come home because he was having a problem with the dishwasher. My father was never abusive or cruel, and after her accident in 2002 he took devoted care of her. But throughout most of their marriage he took her far too much for granted, and the years of tending to his needs often left her in a state of brittle exhaustion.

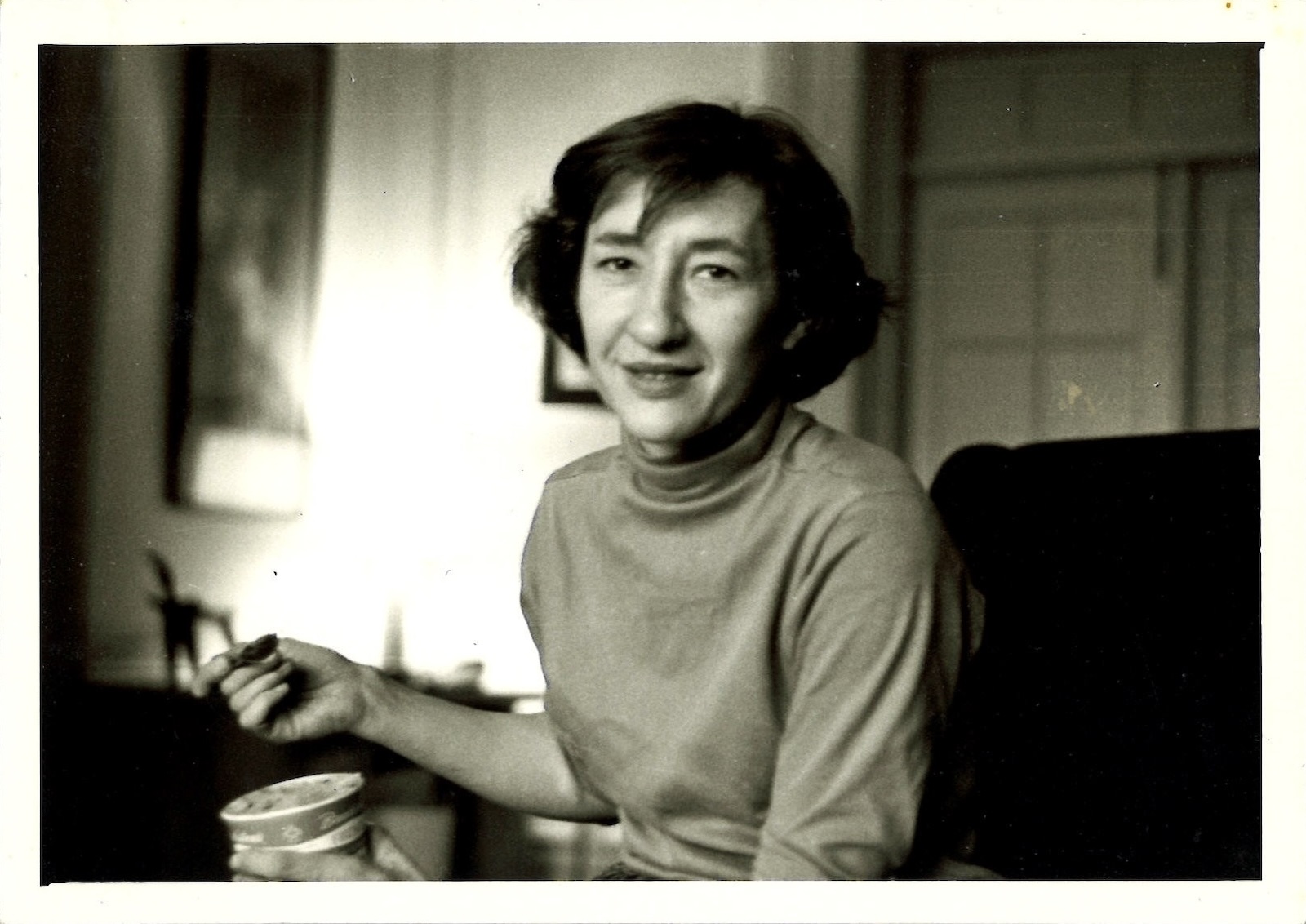

Yet she did, eventually, start to write again. In the early 1970s, once I stopped needing constant care (and before my diabetic father started needing it), she began to contribute regular fiction reviews to the old union weekly The New Leader. I remember well how hard she worked at them. Before starting, she would walk over to the Cambridge Public Library and return with a stack of books—everything the author in question had ever written, as well as similar works by others. She agonized over these essays, and they came out beautifully crafted.

A few years later she became the regular fiction critic for Commentary, leaving the position only when the magazine drifted too far to the Reaganite right. Her criticism was deeply grounded in literary history, always holding contemporary novels up to the standards set by the masters of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It could also have a very sharp edge. Francine du Plessix Gray’s World Without End “is not a novel of ideas, it is an adolescent daydream, an orgy of pseudo-intellectual posturing.” James Baldwin, in Just Above My Head, “has written a novel that drifts and flounders in the riptide of uncertainty.” Mario Puzo’s Fools Die would be better titled Fools Buy. My mother made little money from these reviews, and it was not the fiction she had dreamed of writing, but it pleased her. She did try, late in life, to write a novel, but she never finished it, and I never found the draft.

She particularly liked working on women novelists, and in the 1990s tried to put together a volume of essays on the subject. She wanted to show how “women draw upon unique experience in writing a novel, the literary form that most generously allows them to give imaginative shape and coherence to the particulars of a woman’s life.” But she was severely critical of feminist literary criticism—she felt it dwelled too strongly on victimization and trauma and allowed politics to trump questions of aesthetic merit. In 1970, amid the flowering of women’s liberation, she did call attention in a book review to the “basic truths” that “women have, indeed, been discriminated against, their talents wasted or misused by many institutions and many men for a very long time, and that an end to this inequality is still not in sight.” In the same piece, however, she dismissed Betty Friedan as a “tireless ideological yenta.” Her book never found a publisher.

She remained, always, devoted to her close female friends. When I was a child we spent every summer on Martha’s Vineyard, where she and my father had built a house. It was not an era when parents felt they needed to spend their days guiding their children in carefully selected activities or driving them around. (When I asked to be driven to the local Community Center, she would reply, “You can hitchhike.”) Most days my mother got together with friends who had sons my age, and let us play as we wanted, in the woods or on the beach, while they spent the time talking and always, in my memories, laughing.

My mother’s best essay concerned her friendship with Bishop. It started with her memory of their first encounter at Yaddo, in 1949:

The first time I saw Elizabeth, she was blowing bubbles from a small, elegantly curved clay pipe. As the iridescent globes of fragility rose on the air, floated hesitantly for an instant, and vanished in the summer sunlight, she followed their ascent to oblivion with an affectionate and watchful eye.

In the essay my mother developed the image into a metaphor for Bishop’s emotional fragility. Rereading it now, I wonder if she recalled her own letter to John Brinnin about the “soap opera bubbles broken” after she left London in 1950.

Memories vanish like soap bubbles, too, when the minds that hold them depart. Nearly everyone who knew my mother well is gone now, and their memories with them. I still dream of her, sometimes almost every night. In the dreams she is whole and well, recovered from her accident. I can ask her whatever I want, and she answers. I wake up and know she is gone, and that there is so much I will never learn. But I can try as best I can to peer back, and to see her as she was, fragile and weighted down, but also passionate and brave—the young woman I never knew.