Last fall, Lauren Michele Jackson reviewed Greta Gerwig’s blockbuster Barbie for the NYR Online. With the publication this morning of “Tired of Pink,” her disquisition on Mean Girls and mean girls past and present, she has begun to assemble a corpus on twenty-first century femininity. As she writes, the filmmakers seem to believe that “every generation deserves its Mean Girls,” but this year’s version is hard to recognize: “Mall culture has gone and so, apparently, have acne, segregation, and frizz.” Where the characters in Tina Fey’s original 2004 film weaponized one another’s promiscuity, “in 2024 we do not call each other sluts and whores except as affirmation of an individualized bodily autonomy.”

Jackson is a professor of English and Black Studies at Northwestern University and a contributing writer at The New Yorker, and her work has appeared in, among other publications, New York, The Washington Post, and Harper’s Bazaar. Her criticism focuses on popular culture, and she has brought her sly wit to bear on subjects ranging from SpongeBob to Josephine Baker to Kamala Harris’s public speaking style, with particular attention paid to the slippery movement between black culture and the commodified mainstream. Her next book, Back, forthcoming from Amistad Press/HarperCollins, is a collection of essays about the figure of the back as alternately embodied and idiomatic across American art and letters.

We e-mailed this week about weightlifting, vertigo in the black literary tradition, and the bombardment of Gaza.

Nawal Arjini: Does your writing about pop culture spring primarily from personal interest or from academic questions about culture and society?

Lauren Michele Jackson: A very modest gut feeling, I’d say. I probably have very transparent tastes, though I am not always self-aware enough to know them in advance. And I’m trying to presume less in advance of writing, which has tended to mean that I veer away from the topical method—“What does this have to say about that?,” et cetera—in favor of lingering over the inner workings of the cultural artifact under discussion. This is not the same thing as letting the object speak for itself; a book or film certainly has something to say about society, but it is not itself the world. (Though I’m realizing I get pretty sociological in the Mean Girls piece.) Then again, nobody gets into criticism—or literary studies—to be so modest. Grand statements, however qualified, are the thrill.

As an academic writing about fun cultural objects, how do you resist bringing the full weight of scholarship down on topics as potentially airy as Mean Girls or Barbie?

I find that time nips that instinct pretty well. I still get lightly smacked, in the edits, for freighting (to extend the metaphor) what’s meant to be a frothy, fun thing. But then the whole “academic does pop culture better than you” pose is a little worn out, no? The real answer, I suppose, is that there’s always a limit—whether imposed by format, word count, house style, who has research assistants, and so on—to how citational something can be. I try to honor anything, including casual conversation, that has touched my thinking. Not every domino. Compared to my academic colleagues, I’m such a slouch.

We were chatting in the office about whether the original Mean Girls “holds up,” prompted by a colleague who had seen it for the first time and didn’t think it did—or maybe it was just a strange movie to begin with. What do you think “holds up” means, and does Mean Girls (2004) hold up?

“Historical-feeling” comes to mind as an analog, in which the historical is apprehended as a question of values, or better yet, decorum. People will say that Trump voters are “backward,” relics of a prior age, despite the fact that we are all held together by the now. (And what feels more contemporary than Trump?) But we’re embarrassed. When we watch something that makes us blush or something is said that would make us hush a relative at the dinner table, we’ll say it hasn’t held up. Elements that feel constant or universal or, more relevant to the subject of time, eternal—good humanist stuff—tend to be commended for holding up.

Someone might wince at Regina’s use of the r-word or Cady’s “Africa” moniker (or not!), but still insist upon the quality of the movie’s perennial humor or the necessity of its message, since it’s not as though bullying has gone away. But comedy is also historical, and not only for its social transgression. The rhythms of the turn-of-the-century blockbuster comedy are historical. Tina Fey–ness is historical. But that’s not generally what’s meant about a movie showing its age. Holding up seems to depend on whether or not a present-day viewer must revise their uncomplicated enjoyment of the thing, leaving aside the issue of why that enjoyment was ever uncomplicated in the first place.

Is there anything you’ve wanted to cover, but found ultimately too thin to write about?

Nothing too thin to be inflated by a bighead! Running through the rolodex, I once wanted to write: an impassioned defense of the phrase “the ways in which”; an essay about vomit in Pablo Larraín’s Princess Di drama Spencer, inspired by Eugenie Brinkema on Laura Dern; a piece about whether and why black self-styled auteurs are afraid of Tyler Perry. Currently I’m intrigued by this farce with that little Chiefs fan who painted his face, but that seems very beside the point of anything happening right now. Probably better material for someone’s fiction.

You’re a weightlifter who writes a lot about bodies in settings other than the gym (your inner scholar and your inner meathead, as you once put it, are comfortable companions). Is there ever an overlap?

Other people have written very elegantly on the affinities between exercise and thinking or exercise and writing. I just know that I feel incomplete without regular exercise in a way that writing cannot supplant. (As for overlap, the best gyms I’ve ever attended were campus gyms.) I would like to write more about “fitness culture,” but only if I can find a way to not be boring about it. In my next book, Back, I have an essay that uses powerlifting and bodybuilding and ballet to consider issues of form. It’s been fun to write, figuring out how to close-read a type of lift without turning it into something it’s not. There are also plenty of precedents for this: the most famous bodybuilder in the world wrote poetically about bodybuilding as an athletic and aesthetic discipline. Bodybuilding in general has a real fetish for classicism.

For the University of Chicago, you wrote your dissertation about “Black Vertigo: Attunement, Aphasia, Nausea, and Bodily Noise.” This sounds fascinating—would you mind explaining it a bit?

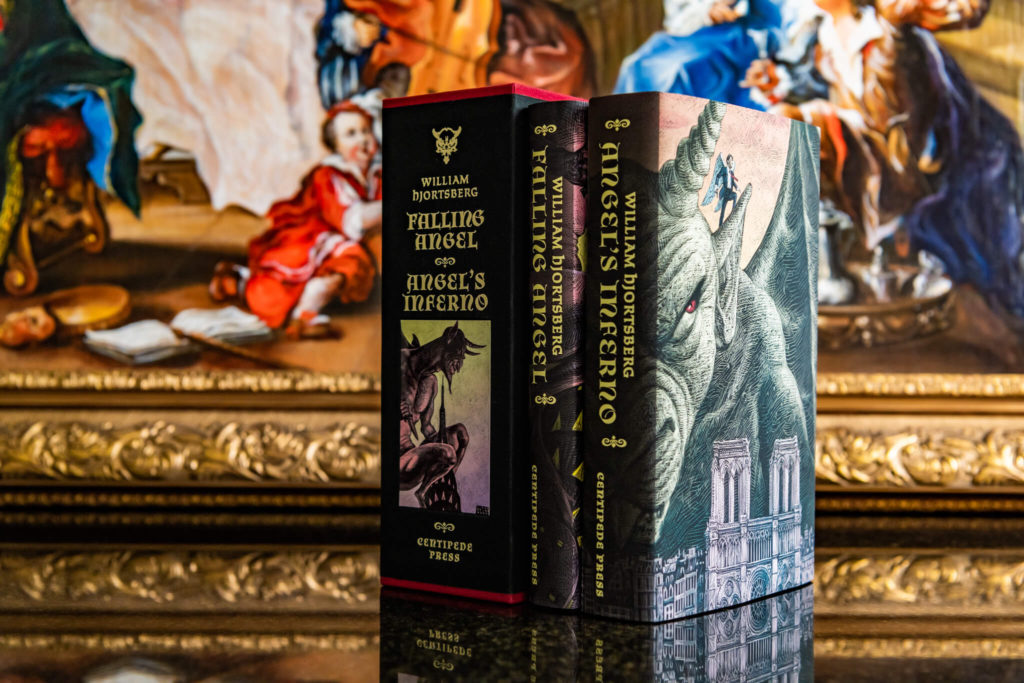

I’m going to do the commendable thing and not look it up. Basically, my dissertation reads vertigo as an affect or literary device or analytic by which various authors and artists represent blackness and its vicissitudes. The larger and more tenuous claim is a historical one, that vertigo—figured as dizziness, aphasia, nausea—emerges as the dominant mode (or whatever) for cohering a black literary tradition after the 1960s. There are some good readings in there, I think, and it’s pleasant to talk about it as a static object. I disagree with so much of it now. I want to, in my next book after Back, “the monograph,” if we still call them that, reassess the premises of that project, including some bad habits I think literary studies has picked up from black studies as regards reading, or lack thereof. It’s called The Come Down, at least for now, a study of literary devices that undermine hermeneutical notions of a contemporary black literature.

Going even further back, do you think of any piece of culture or scholarship as particularly formative to your intellectual work or personal interests today?

The nineteenth century got me into this biz and there I might return someday. Me on Hawthorne, can you picture it?

We’re coming to the end here, and so I must seize upon inelegance to say that Israel is bombing Rafah as I write this. It’s been four months and seventy-five years of Israel’s assault on Palestinian life, displacing, maiming, and massacring people in a US-backed campaign of mass death. A people being starved while Israelis along the border block aid trucks, and while professional equivocators hem and haw in editorials for the easily duped. I just implore anyone reading this wherever you are: go out and speak the truth.