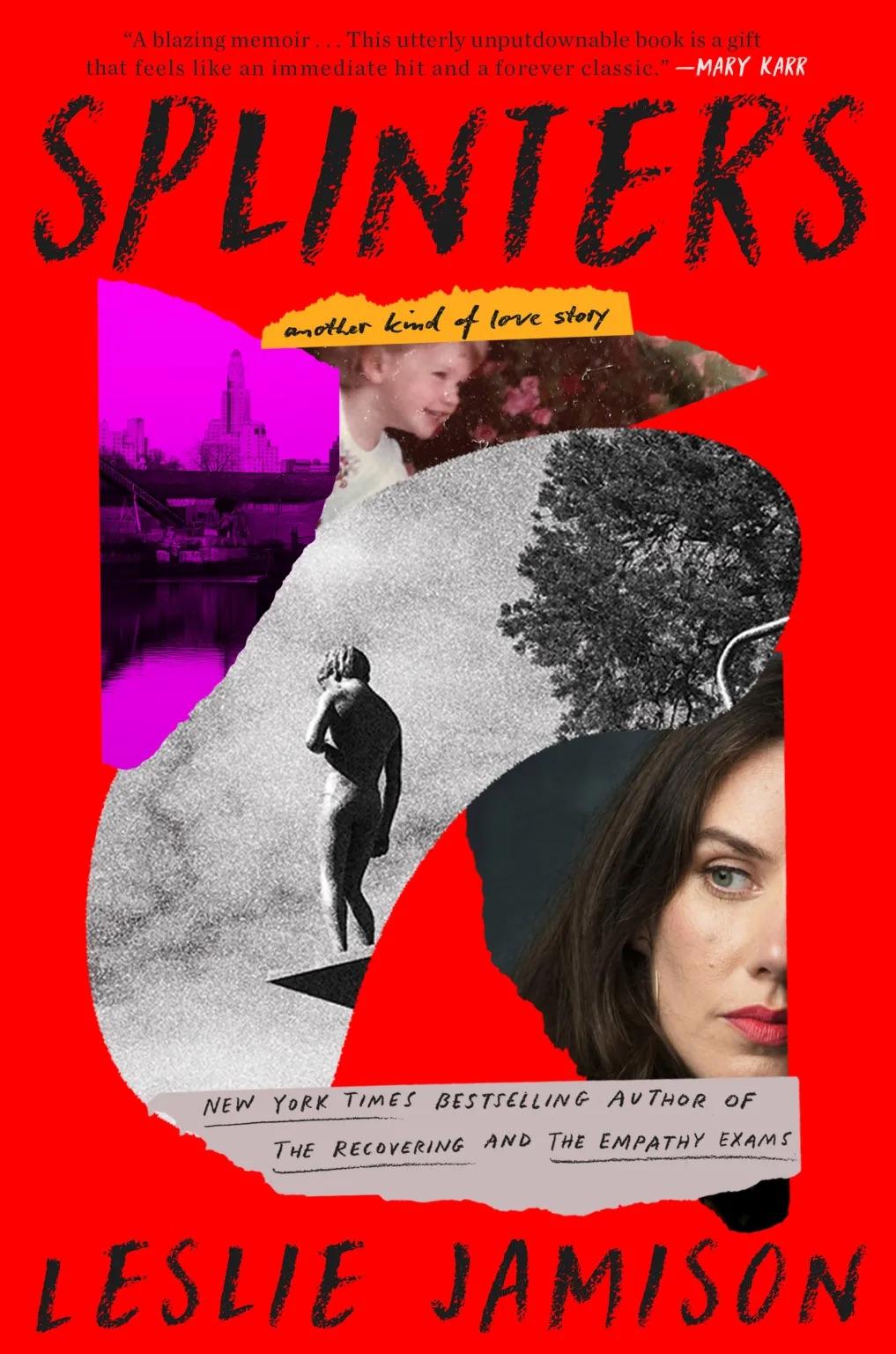

Splinters narrates the author’s rigorous transformation from maiden to mother. Jamison recounts the birth of her daughter, the dissolution of her marriage, and the early days of single parenthood; the result is a cunningly written story about the sacred, sometimes tedious capacity of small children to ensnare time. Reflecting on past familial and romantic relationships, Jamison concludes that “[w]e aren’t loved in the ways we choose. We are loved in the ways we are loved.” It’s a half-answer to the question that wholly preoccupies her: is she allowed to want what she wants, even if the pursuit of those desires hurts other people? Jamison’s book-length tussle with this question, set down in vivid prose that not only is unafraid of self-incrimination but also seems, actively, to seek it, treats us to a gloriously noisome record of rehabilitation and discovery.

On that note, The New Yorker did Jamison a disservice by removing the “loud wet farting” and “sudden and vegetal” smell of her infant daughter’s shit from the excerpt published in the magazine. It’s in the frequent interruption of shit—and vomit, and profanity, and the outrageous self-centeredness of the men in whose company Jamison finds herself—that the writer’s loving and dedicated collection of domestic minutiae reveals its profundity. Motherhood is a rush of meaning compressed into endless, repetitive tasks (Ursula K. Le Guin once observed that housekeeping is the “art of the infinite”). Of the aforementioned “sudden and vegetal” fecal odor, Jamison writes: “Sometimes I couldn’t get enough of that smell.” But the poetry intuited in her daughter’s poop eludes her. “[W]hen I tried to record it, it was hard to figure out why. She took the biggest shit, I wrote. It got all over us both.”

¤

Blogs rarely get their due in discussions of literary nonfiction. Yet it’s hard to ignore how closely Jamison’s warts-and-all account of motherhood hews (tonally, at least) to the popular output of 2000s mommy bloggers like Heather Armstrong, whose website prioritized candor and emotional honesty over smooth edges. Here, Jamison—an award-winning author, frequent New Yorker contributor, and tenured Ivy League professor—writes of her infant daughter, “She was more like my guru than my child.” She parodies her passion for her new role in a scene from her teaching: “I told my students how motherhood was sharpening my gaze, every single day, deepening my appreciation of the mundane, asking me to focus on the smallest—‘Leslie,’ one of my students interrupted, ‘I think your daughter might be choking on a grape?’” By refiguring the fundamental romance as taking place between mother and child, Splinters offers an escape from the marriage plot; somewhat ironically, the love Jamison harbors for her daughter makes it possible to sever the family she’d once made with the man who becomes her ex-husband.

Falling in love with that man—C, a widower with a young child whose presence is completely scrubbed from Jamison’s book by mutual agreement—“was encompassing, consuming, life-expanding.” Their initial ecstatic and deeply intellectual connection (Jamison returns many times to a diner breakfast during which she rushed back to the table from the bathroom, so eager was she to continue their conversation) gave her a vehicle to escape from a lifelong habit of second-guessing her choices: “My desire to feel certain was so strong it started to feel like certainty itself.” But the relationship is mercurial, its fledgling heights giving way quickly to painful depths. Early on, C gets a tattoo of Jamison’s face. A few short years later, he sneers when she tells him she and the baby have had a good day. Yet Jamison calls him “loyal” or refers to his “loyalty” no fewer than five times; it’s her favorite word for a hard-to-describe quality that not only compels her to marry him but also casts doubt upon her decision to leave him.

It may seem difficult to locate loyalty in a man who hisses, “Don’t act like you’re fucking scared of me” in couples therapy, but it’s not loyalty to Leslie Jamison that her book describes. “The memory was so painful it cut through him, like a splinter breaking through the surface of his skin,” she writes of a moment (one of many) when C shares an intimate detail about his first wife’s death. This is the emotional authenticity that allies Jamison to C, and the idea from which her book derives its name: here is a man well familiar with what life can take from you.

Necessarily, the memoir is hindered by a custody agreement and Jamison’s awareness that her ex—and, someday, her daughter—will almost certainly read it. Although she dedicates many pages to painstaking personality-deconstruction of the two fuckboys she dates after her divorce (when the boyfriend with a face Jamison describes as “hard to remember” remarks that “[i]t feels like our conversations are about 85 percent as good as they could be,” I wanted to hiss, That’s Leslie Jamison you’re talking to), C remains frustratingly remote. Yet a big part of C’s allure, it becomes clear over time, is that very remoteness—and the opportunity it offers Jamison to prove her worth to a withholding paternal figure. The same goes for the fuckboys: Jamison connects her desire to please these seemingly unpleasable men to her often absent, imperious father. “With your father, at least I was never bored,” her mother tells Jamison of her adulterous ex-husband; in a memory, Jamison is in the seventh grade when her dad, upon learning that she received a B− in her world cultures class, remarks, “This isn’t you.” Jamison decides then: “Whatever the opposite of getting a B− was, I would spend the rest of my life doing that.”

When she becomes a mother, Jamison finds herself unable to submit to this imbalanced dynamic of performance and evaluation any longer. In her words, she “did not want to create a home where the main measures of love were hardship, expenditure, and burden.” So she leaves, moving with her daughter into a “long and dark” sublet a friend nicknames the “birth canal,” in and from which she commences several years of exploration and healing.

For all its pleasures, and its renunciation of relationships with men, Splinters is an almost shockingly heteronormative book. In it, daddies—especially Jamison’s own—are walled off in towers of mood and pretension yet granted effectively endless forgiveness by women who insist that, in fact, they are loved by these unkind and often absent figures. Any queer people are mere talismans, benign visitors from an alternate universe. A drag show attended in the early days of Jamison’s custody arrangement feels exaggerated in its transcendence, an outsize source of “permission and exhortation.” And Jamison describes the cozy regularity of her lesbian friends’ domestic scene, with their crates of seltzer on the porch (untold amounts of seltzer are consumed in this book), as “more like magical realism than documentary.” That’s how hard it is for her to imagine a way out of the gendered dichotomy that both gives the book its narrative engine and sets the limits of its track.

¤

Jamison’s own mother is a focal point of Splinters, a superheroic force ever available to swoop in and provide childcare so that Jamison can go on book tours of unreal proportions (40 dates with a per diem? In this economy?), to a dreamy literary event in Capri, or on the road with her first rebound, a musician she calls “the tumbleweed.” Her memories of their child’s first days feature C glowering alone in his office while Jamison’s mom brings her cheese plates and holds the newborn. Like mother, like daughter: Jamison recounts her own, endless maternal receptivity to any labor demanded of her by others. “They didn’t know it, but they were all my children,” she writes of her students. “My beehive heart had enough love for all of them.”

By contrast, descriptions of her daughter’s caregiver Soraya have a retrograde flatness. Jamison writes of the “bright silk scarves wrapped around her hair,” of her supernatural competence with children, and of her recipe wisdom doubling as life advice: “I’d thrown away the most important parts, she explained, and cooked the parts I should have thrown away.” When Jamison comes home late, crying because she knows her daughter has been waiting to breastfeed, Soraya comforts her. “This was part of the labor I was asking of her, to assuage my guilt about the labor she was providing,” Jamison writes, assuming her usual tone of self-abnegation. It’s a self-aware statement, but it doesn’t unpack the actual terms of Jamison and Soraya’s arrangement.

When I was pregnant and anxiously researching what kind of childcare my partner and I would be able to afford when our parental leaves ran out, I asked the parents I knew how much their solutions had cost. Almost everyone told me they couldn’t remember, which seemed impossible, because the money was all I could think about. It stood in for every looming unknowable—as well as being just itself, money, an inescapable necessity.

Of course, what I really wanted to know was even more intimate: Where did the money come from? How did anyone make it work? In a way, the answer didn’t matter: I knew it would cost more than I could afford. Impoverishment seemed built into the very situation of having a child, a closed door at which I impudently knocked.

Jamison’s exceptional qualities and circumstances—her beehive heart, her professorship at Columbia—can make Splinters an occasionally frustrating read. After a nonconfrontation with a male colleague over whether she can have their shared office to herself to pump breast milk, she channels her shame and frustration into an attempted commentary on the circumstances of professional mothers:

I tried to imagine being a student looking for space to pump, or an adjunct teacher worried about getting asked back. Or a maintenance worker. Which is to say, We aren’t all in the same boat.

Still, it made me smile to conjure a version of this impossible boat: men and women alike hooked up to breast pumps all day long, tits out in the sun, squinting against the salt breeze, fortifying themselves with granola bars, pumping and pumping away.

It’s the rare moment in the book that feels inauthentic, one of a few gestures toward class consciousness that pivots—typically, with a joke—to an unearned collectivism. Once, she cracks a window on the desires underlying her dreams of well-heeled brownstone family life, yet immediately puts up a screen: “[I]t had more to do with the fantasy of someone kneading the hard concrete of my shoulders at the end of the day, and telling me to put down everything I was carrying.” Sure, and maybe she wants a partner who is financially as well as emotionally supportive—but money is the book’s biggest taboo, a topic Jamison is clearly uncomfortable broaching. Only in the book’s final quarter does she cop to something alluded to early on when describing the disjuncture between her career and C’s: “I’d been paying the bulk of the bills for years.”

Missed opportunities to engage with often illogical variances in literary fortune, or even just plain old fortune, can make Splinters feel less substantial than it wants to be. However far Jamison has come from the woman who married a man to make good on a secret wager against doubt, she’s still trying hard to please—and finding fault with herself instead of the system that has elevated her as one of its chosen few. In a book that so fearlessly amplifies intimate detail—the chlamydia Jamison catches from the tumbleweed, the perplexing statement about “ways I’d never been fucked” (I guess they did anal, I wrote in my notes)—it’s disappointing to find so little attention paid to the unique subject position of the author.

¤

If Jamison’s memoir can be distilled to a central concern, it’s one of labor—the labor of childbirth, of motherhood, of teaching, the emotional labor required by relationships. Yet curiously, the narrative largely leaves out the work and craft of writing itself. “Whenever I spent hours of childcare writing nothing but terrible sentences, I always felt like I’d failed my daughter—wronged her, even—by squandering the time away from her,” Jamison writes, midway through the book. That the sentences are generally excellent is an object lesson of its own: she is determined not to wrong her daughter, and she succeeds. She does well, as she believes she must in order to be loved.

Splinters is a book about a woman who struggles to see herself clearly after a lifetime of being taught to find herself in the needs of others. This is an eternal danger for women, and mothers especially, a plight Jamison shares with the troubled Teen Mom cast and with Heather Armstrong, who died by suicide last year. But what makes Jamison’s memoir remarkable is its happy ending. Seemingly to its author’s surprise—although really in demonstration of her skill—the book provides a record of Jamison shrugging off a prewritten life and embracing the process of discerning her own.

By the time quarantine lockdowns have eased, Jamison is riven and healed by the inherent contradictions of her new life as a mother. “It was okay to want cigarettes at the beach, and bone broth underground,” she writes, adding: “My daughter broke me open for the whole world. She broke me open for everything that wasn’t her.” In other words, Jamison has undergone an irrevocable change and gained an opportunity to see herself anew. Her mother-self becomes a lamp that lights the way forward—and a beacon to help her look back and identify the moments, places, and people in which and with which she began to embody her whole self, all its contradictory yet nourishing identities included.

At the end of any given span of mothering, I am both exhausted and already nostalgic for the experience I wanted to end. Every cliché is true: the days are long, the years are short, the time passes right in front of my eyes. Perhaps the most resonant description of motherhood I’ve read, in Lydia Kiesling’s 2018 novel The Golden State, posits that it may be

some well-trod but magnificent place you’re only allowed to sit in for a minute and snap a photo before you are ushered out and you’ll never remember every individual jewel of a room but if you’re lucky you go through another and another and another and another until they finally turn out the lights.

What rooms Jamison will pass through, what photos she’ll snap—these are the subjects of future memoirs. Before her death, my mother posted on Facebook a photograph of herself in our backyard hammock with my younger sister, then a few months old. It was a carefully staged portrait, a touch of the absurd in its glamour. Still, posed or not, the impulse behind the photo was real: the image of herself as a mother was what she wanted finally to share.