Aaron Lansky was a young graduate student in Montreal in the late 1970s when he had an epiphany that changed the course of his life.

He had been taking courses in Yiddish literature at McGill University, but was finding it hard to find the books he needed. At times, he relied on older neighbors in Montreal’s vibrant Jewish community who would welcome the opportunity to chat with a young visitor over a cup of tea or a plate of noodle kugel before surrendering their books.

He came to realize that such home libraries were endangered resources: The generations of Yiddish-speaking immigrants who flocked to the United States and Canada beginning in the 1880s to escape pogroms and poverty were dying out, and most of their assimilated children and grandchildren did not speak or read Yiddish well. As a result, whole libraries filled with works of writers like Sholem Aleichem, I.L. Peretz and Sholem Asch — as well as science and history texts, translations of classics like Shakespeare and Guy de Maupassant, even cookbooks and sex manuals — were being consigned to dumpsters, attics and cellars.

That wintry day, Lansky, then 24 years old, decided on a seemingly quixotic quest: “To save the world’s Yiddish books before it was too late,” as he writes in his 2004 memoir, “Outwitting History.”

He took a two-year leave of absence from graduate school, recruited teams of volunteer collectors, or zamlers, and got to work schlepping cardboard boxes from scores of homes, schools and synagogues across the country and ferrying them to a 6,000-square-foot factory loft in western Massachusetts.

Scholars had estimated that there were about 70,000 books waiting to be rescued. Lansky went on to gather 1.5 million Yiddish books — a trove that evolved into the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Mass., one of the nation’s leading Jewish cultural institutions.

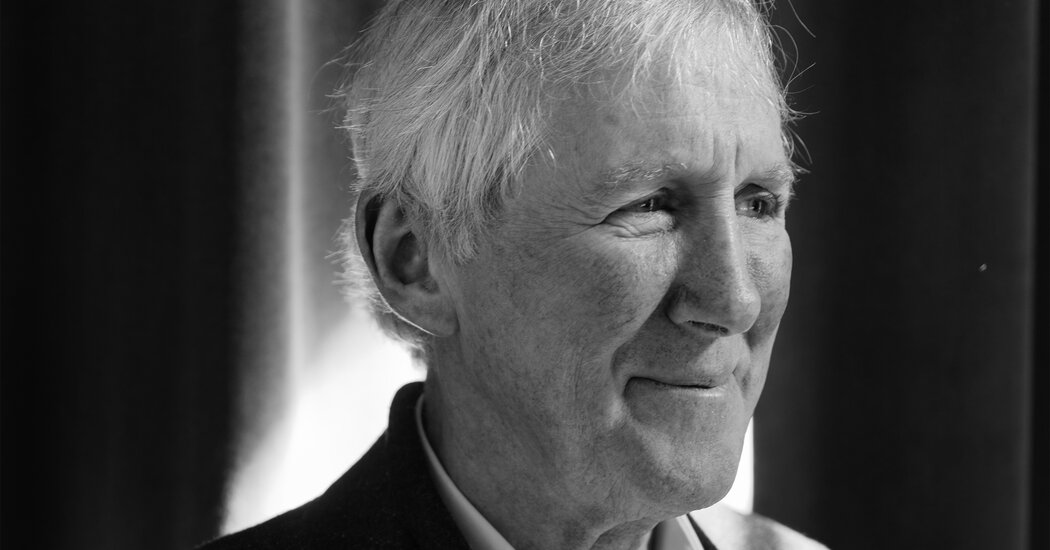

His quest nearly complete, Lansky, 68, who won a MacArthur fellowship in 1989, announced on Tuesday that he will retire in June 2025 as the center’s president (He will, however, remain for another two years as a senior adviser.) Susan Bronson, who has been the center’s executive director for 14 years and holds a doctorate in Russian and Jewish history, will take over the position.

Sam Norich, president of the association that publishes The Forward — a newspaper founded in 1897 as a Yiddish daily that is now published online in English and Yiddish — said Lansky deserves enormous credit for building the organization “from scratch” at a moment of historic transition in the Jewish American community.

Lansky, he continued, “had the genius to dramatize” the transmission of the Yiddish legacy “both for the old people who were handing it off and for the young enthusiasts who were accompanying him.”

With the instincts of a Broadway press agent, Lansky sent out appeals to newspapers, wire services and Jewish organizations who publicized his search. Locating the center away from New York City, “where he would have been squeezed and controlled” by the seasoned leaders of other Yiddish and Jewish organizations, was also smart, Norich said.

Part museum, part library, part bookstore, part storehouse, the center is now based in a 10-acre complex on the campus of Lansky’s alma mater, Hampshire College, where two buildings are designed to appear like an East European shtetl, or a small town.

The book collection, along with Yiddish libraries of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, the New York Public Library and the National Library of Israel, has been undergoing digitization so that anyone can go to its website, search for a title or author and call up an entire book. Lansky estimates that the four organizations together possess 99 percent of all the Yiddish book titles ever published. So far 11,000 titles from the center’s collection have been digitized and have triggered five million downloads.

“It’s a wonderful vindication that Yiddish, on the verge of extinction, will now be the first fully accessible literature in history,” Lansky said.

The center has also done much to bolster Yiddish language and literature. It has distributed duplicates in its collection to libraries and museums around the world and commissioned translations of Yiddish books into English, particularly those by female authors whose works were never accorded the same esteem as those by their male counterparts. The center runs summer classes in Yiddish and has produced a new two-volume text for students taking basic Yiddish courses. Thanks to Bronson’s initiative, the center has sponsored a summer music festival called Yidstock. And a publishing arm, White Goat Press, has turned out 20 books since it began in 2019.

“Everything I dreamed of, I’ve been able to do,” Lansky said. “Not many people can say that.”

Although the Torah is written in ancient Hebrew and the Talmud in Aramaic, Yiddish was the mamaloshen — the mother tongue — of the Ashkenazi Jews of Eastern and Central Europe. It emerged in the Rhineland and other Germanic lands more than 1,100 years ago, its speakers adopting Hebrew lettering but retaining the Middle High German vernacular in conversation and writing. Over the centuries it has borrowed words from Slavic and Romance languages and enriched those languages as well. Words with a distinctive Yiddish nuance like kibitz, tchotchke and chutzpah spice up the conversations of countless Americans.

The ranks of speakers were decimated with the murder of six million Jews in the Holocaust — two-thirds of the Jewish population of Europe. Although Yiddish remains the everyday language of many Haredi and ultra-Orthodox Jews, they spurn nonreligious books, plays and movies. Death and assimilation have also shrunk the numbers of secular Yiddish speakers in the United States and other pockets of Jewish life to no more than 150,000, Norich estimates. So it is a handful of organizations like the Yiddish Book Center that keep the embers of the language burning, catering to young people curious to investigate the mother tongue of their grandparents.

Lansky, who lives in Stockbridge, Mass., with his wife, Gail, wants to use his time in retirement to write and study. Finally, he said, he’ll “have time to read some of the books we’ve been saving.”

When he looks back, he added, his fondest memories are of the people who turned over their books, delighted that someone had found a home for them.

“I think I’m one of the luckiest people in the world,” he said. “I got to sit at the kitchen table with literally thousands of Jews who were bequeathing their greatest treasure to me.”