A 2,800-year-old burial containing the remains of an elite individual was identified in Siberia. Experts believe that the culture responsible for the burial would have been closely related to the Scythians, a group of nomadic tribes who lived in the Eurasian steppe in antiquity, given the elaborate horse sacrifices found at the tomb.

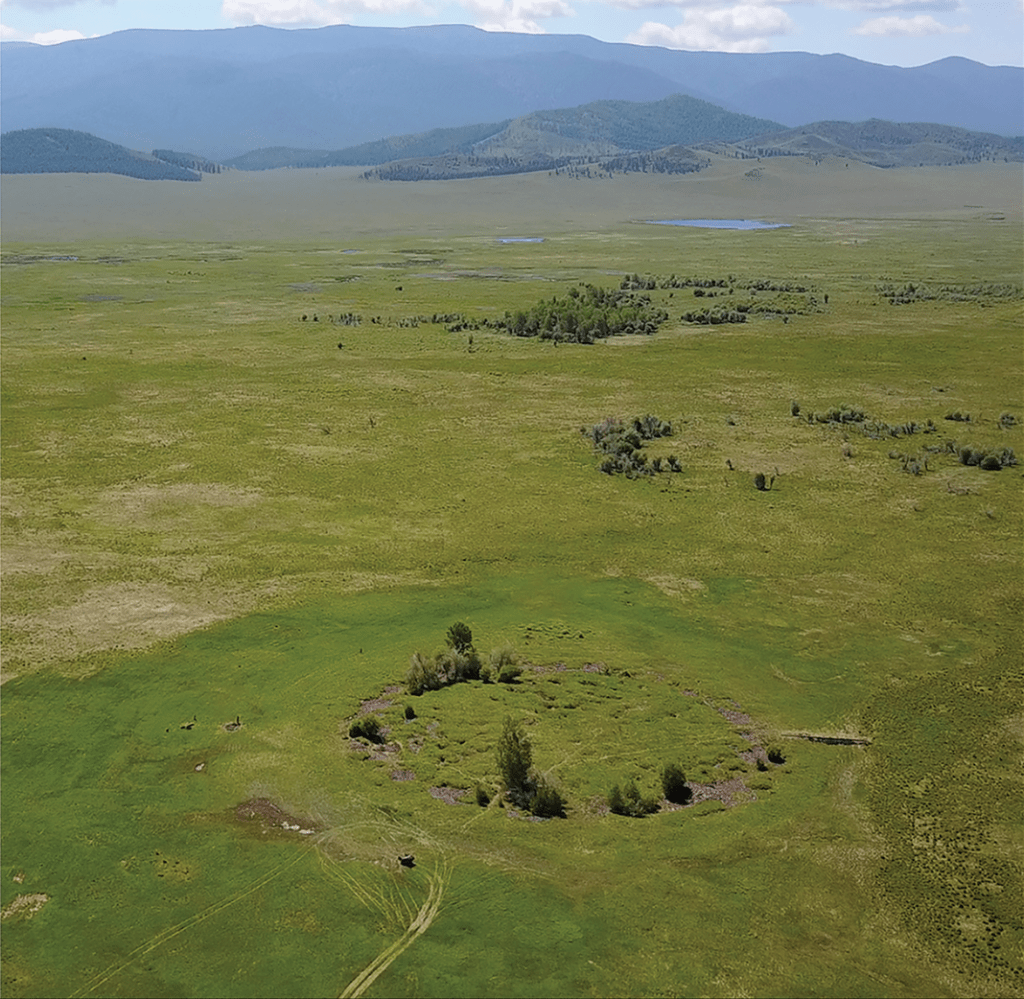

An excavation of a kurgan, or a large burial mound, in Tuva, a republic in southern Siberia, revealed the remains of a woman believed to be a human sacrifice and 18 sacrificed horses with brass bits between some of their teeth, along with horse-riding gear and artifacts decorated with animals.

The find dates back to the late 9th century BCE—a time marked by transition between the Bronze and Iron Ages—making it one of the earliest-known examples of Scythian burial practices, according to a study published in the journal Antiquity.

The Scythians, however, are known to have lived thousands of miles west of this kurgan. Leaving no written record, they are thought to have trained and ridden horses, created animal art, and performed ritual sacrifices. Others who encountered the Scythians wrote about them, including the Greek historian Herodotus, who lived roughly from 484 BCE to 420 BCE.

Herodotus detailed elaborate sacrificial burial rituals for Scythian royalty during the 5th century BCE, including the sacrifice of servants and horses by the the dozen. The horses would subsequently be gutted and stuffed. Both the sacrificial humans and horses alike were then propped up with wood around the burial mound.

The origins of Scythian culture remains unclear. This kurgan is located in what is known as the Siberian Valley of the Kings, meaning that no other sizable find related to Scythian culture has ever been found as far east as this.

The discovery also demonstrates connections between the nomadic Scythian group and the early establishment of horse culture in Mongolia, which adapted some of these practices.

“Unearthing some of the earliest evidence of a unique cultural phenomenon is a privilege and a childhood dream come true,” Gino Caspari, study senior author and archaeologist at the University of Bern in Switzerland, told Live Science.