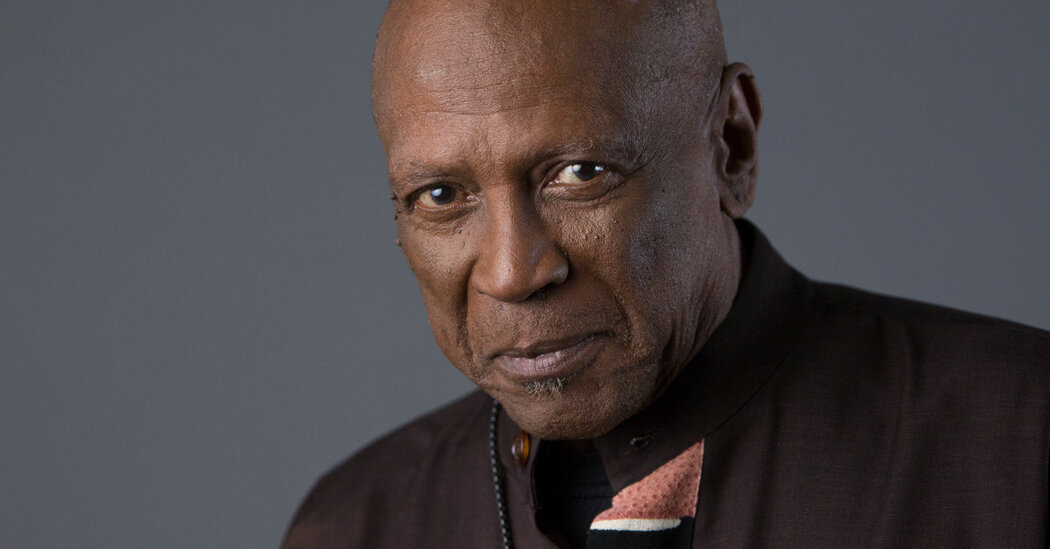

Louis Gossett Jr., who took home an Academy Award for “An Officer and a Gentleman” and an Emmy for “Roots,” both times playing a mature man who guides a younger one taking on a new role — but in drastically different circumstances — died early Friday in Santa Monica, Calif. He was 87.

Mr. Gossett’s first cousin Neal L. Gossett confirmed the death. He did not specify a cause.

Mr. Gossett was 46 when he played Emil Foley, the Marine drill instructor from hell who ultimately shapes the humanity of an emotionally damaged young Naval aviation recruit (Richard Gere) in “An Officer and a Gentleman” (1982). Reviewing the movie in The New York Times, Vincent Canby described Sergeant Foley as a cruel taskmaster “recycled as a man of recognizable cunning, dedication and humor” revealed in “the kind of performance that wins awards.”

Mr. Gossett told The Times that he had recognized the role’s worth immediately. “The words just tasted good,” he recalled.

When he accepted the Oscar for best supporting actor in 1983, he was the first Black performer to win in that category — and only the third (after Hattie McDaniel and Sidney Poitier) to win an Academy Award for acting.

He had already won an Emmy as Fiddler, the mentor of the lead character, Kunta Kinte (LeVar Burton), in the blockbuster 1977 mini-series “Roots.”

Fiddler, an enslaved man on an 18th-century Virginia plantation, was, as the name suggested, a musician. Mr. Gossett was not thrilled about the role at first. “Why choose me to play the Uncle Tom?” he remembered thinking in a 2018 Television Academy video interview. But he came to admire the survival skills of forebears like Fiddler, he said, and based the character on his grandparents and a great-grandmother.

That portrayal, he said, became “a tribute to all those people who taught me how to behave.”

Louis Cameron Gossett Jr. was born on May 27, 1936, in Brooklyn, the only child of Louis Gossett, a porter, and Helen (Wray) Gossett, a nurse. He made his Broadway debut when he was 17 and still a student at Abraham Lincoln High School on Ocean Parkway.

While healing after a basketball injury, he appeared in a school play, just to occupy his time. Impressed, a teacher suggested that he audition for “Take a Giant Step,” a play by Louis Peterson that was opening at the Lyceum Theater in the fall of 1953. He won the lead role, that of Spencer Scott, a troubled adolescent. Brooks Atkinson of The Times praised his “admirable and winning performance,” one that conveyed “the whole range of Spencer’s turbulence.”

Sidney Fields devoted a column in The Sunday Mirror to the young man, who shared his career plans. “I always wanted to study pharmacy,” Mr. Gossett said. “But now after college I’ll try acting. I know it’s a tough business, but if I fail, I’ll have the pharmacy degree to fall back on.”

He ended up majoring in drama (and minoring in pharmacy) while on a basketball scholarship at New York University. In 1955, he returned to Broadway, in William Marchant’s comedy “The Desk Set.” By the time he graduated, acting was paying him more than any basketball team would.

He made his film debut as an annoying college man in “A Raisin in the Sun” (1961), an adaptation of the Lorraine Hansberry play that starred Sidney Poitier and Ruby Dee. He had appeared onscreen only twice before — in two episodes of “The Big Story,” an NBC drama series, in 1957 and 1958.

Before becoming a film star, Mr. Gossett had sustained a thriving theater career. In less than a decade he landed six Broadway roles, including that of a Harlem hustler in “Tambourines to Glory” (1963), a South African grandfather’s servant in “The Zulu and the Zayda” (1965), a lawyer who had killed a white man in a civil rights demonstration in “My Sweet Charlie” (1966) and the Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba in “Dangerous Angels” (1971).

In the mid-1960s, he replaced the actor playing the big-time boxing promoter Eddie Satin in the musical “Golden Boy,” starring Sammy Davis Jr. His most unfortunate role may have been as a Black man with a white slave in “Carry Me Back to Morningside Heights” (1968), a comedy written by Robert Alan Aurthur and directed by Sidney Poitier. The play, which Clive Barnes of The Times called racist, closed after a week.

Mr. Gossett never committed to another Broadway role. But he appeared for four nights as the flashy lawyer Billy Flynn in the musical “Chicago” in 2002.

His dozens of feature films included “The Landlord” (1970), in which he played a man on the brink of insanity; “Travels With My Aunt” (1972); and “The Deep” (1977), as a Bahamian drug dealer. His later films included “Diggstown” (1992) and the movie version of Sam Shepard’s “Curse of the Starving Class” (1994).

Mr. Gossett was seen in more than 100 television series, ranging from lighthearted comedies like “The Partridge Family” to dramas like “Madam Secretary.” He played the title role, a Columbia anthropology professor who investigates crimes, on the short-lived 1989 series “Gideon Oliver.”

Mr. Gossett also appeared in many television movies, among them “The Lazarus Syndrome” (1978), about a cardiologist; “A Gathering of Old Men” (1987), about a Black man who kills in self-defense; “Strange Justice” (1999), about the Clarence Thomas Supreme Court confirmation process (he played the presidential adviser Vernon Jordan); and “Lackawanna Blues” (2005), based on Ruben Santiago-Hudson’s play. His other TV-movie roles included the Egyptian leader Anwar Sadat and the baseball star Satchel Paige.

He was seen last year in the film version of the Broadway musical “The Color Purple.”

Mr. Gossett’s marriage to Hattie Glascoe in 1964 lasted only five months.He and Christina Mangosing married in 1973, had one child and divorced after two years. His 1987 marriage to Cyndi James Reese ended in divorce in 1992.

Mr. Gossett is survived by his sons, Satie and Sharron Gossett, and several grandchildren.

In the Television Academy interview, Mr. Gossett urged fellow actors to help effect political and social change in a disturbing world. “The arts can achieve it overnight,” he said. “Millions of people are watching.” He added: “We can get to them quicker than anybody else.”

Michael S. Rosenwald contributed reporting.