This choice of locale might seem unusual for an African American expat, given the centrality of Paris as the postwar pilgrimage site for artistically inclined Black émigrés fleeing US racism. Like so many of them, Carter wanted to be a writer, an ambition he would pursue in the predominantly white, German dialect–speaking, small-town capital of Switzerland. The Bern Book is a generically mixed slice of autobiography, at once a travelogue, an ethnography, a historical portrait of a city and its inhabitants, a social psychology, and a cultural critique of Switzerland. Carter had finished the account by 1957, but it appeared in its original English almost two decades later in New York.

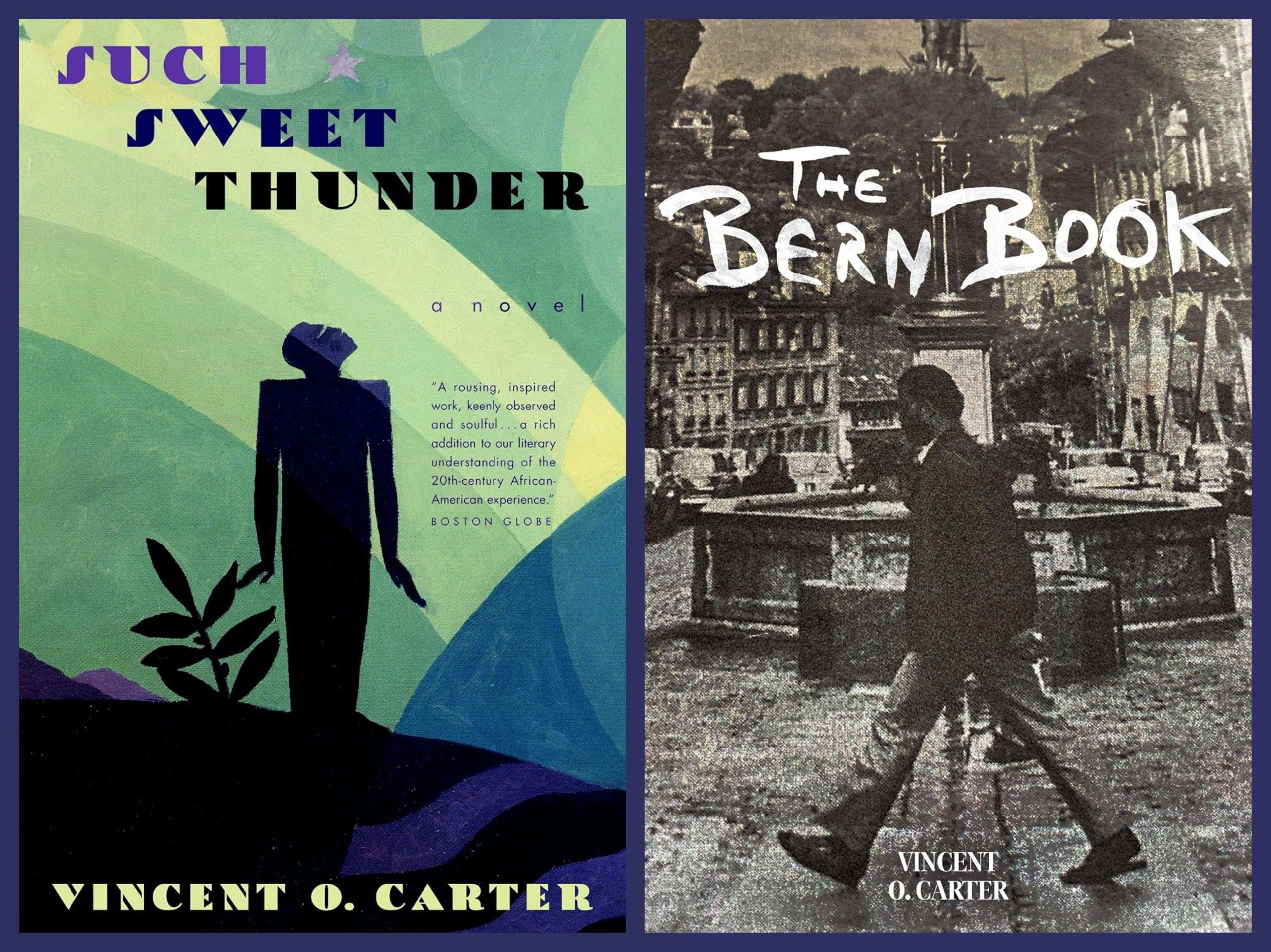

Following The Bern Book, Carter produced another book-length manuscript, initially entitled The Primary Colors, about a boy, Amerigo Jones, growing up in Kansas City in the 1920s and ’30s. Although the text is not an overt autobiography, Amerigo is definitely an author-inspired figure. The manuscript was finished in 1963 but made it into publication only thanks to an improbable series of coincidences 40 years later, long after Carter’s death in 1983, under the new title Such Sweet Thunder (2003).

In a 1970 essay published in Cultural Affairs, Herbert R. Lottman, Publishers Weekly’s European correspondent and an eminent literary biographer, sought to arouse critical interest in Carter’s work. The piece drew attention to the largely unknown writer, whose unpublished memoir had crossed Lottman’s desk. When The Bern Book was finally published three years later, it featured Lottman’s essay as a preface. The preface mentioned two further manuscripts by Carter: one, titled The Long Green Way, did not impress him very much, but the other, Primary Colors, did. Three decades later, Chip Fleischer, editor at Steerforth Press, learned about Carter and, after some sleuthing, obtained the novel’s manuscript from the author’s former partner, Liselotte Haas. Fleischer tells this story in the afterword to the paperback edition of Such Sweet Thunder, where he also explains the change of title and the decision to eliminate the opening 40-odd pages of the original version the press had brought out earlier that year.

The Bern Book, by then almost forgotten, was republished in 2020 by Dalkey Archive Press and appeared in a German translation (as Meine weisse Stadt und ich: Das Bernbuch,) in 2021, thus giving German-speaking readers, notably the people of Bern, their first opportunity to see their city in Carter’s depiction from seven decades past. It’s a fascinating portrait of a placid, mostly white city seen through the eyes of a Black man who is attempting to carve out a space there for himself. Its German title, which adds the phrase “My White City and I,” recenters the focus to one of the book’s central themes, race, a shift noted by Anne-Sophie Scholl in her insightful review of the book for the German weekly Die Zeit. The German-language edition has been well received; indeed, more open to diversity than they were at midcentury, the Bernese like it so much that they adapted a stage version, whose run was extended by popular demand.

Carter’s belated recognition is unfolding simultaneously in two very different cultural contexts, with their vastly different histories of race. In the United States, Carter’s reception has focused on the recovery of a lost Black voice from the midcentury Midwest, where there were not too many such voices (though the Kansas City of Carter’s youth was a center of jazz and Black culture, a fact recognized in the title Such Sweet Thunder, which alludes to both Duke Ellington and Shakespeare). In Switzerland, Carter’s work has become a touchstone of (racial) self-reflection and a critical assessment of Swiss attitudes toward otherness. After Carter, Swiss literature “is white no longer, and it will never be white again,” to cite James Baldwin’s memorable last line from his 1953 essay “Stranger in the Village.” Given these different contexts, and also the respective settings of the two books, Such Sweet Thunder is the American story (not yet translated into German) while The Bern Book is the Swiss story. Only their combination can give us a full picture of Carter, the writer and the man.

¤

Both novels are bildungsromans of sorts. Such Sweet Thunder is a compelling study of an adolescent Black male, the son of poor teenage parents, who comes to realize that a high school degree is the ticket to a better life as he navigates social pressures (and girlfriend troubles) in segregated, rough-and-tumble 1930s Kansas City. The story features a self-confident, slightly ironic third-person narrator who sketches out domestic and public scenes thick with life, handing the speaking roles to characters who don’t lack for opinions and rarely hesitate to announce them. The modernistic narrative offers a kaleidoscopic stream of events; a cacophony of sounds and voices, smells and sights; and a tapestry of sensuality, focalized through the members of its varied crowd. The older narrator musing on the intimate experiences of his young protagonist is clearly a surrogate for the author, whose depiction of the Black community of his youth is at once a meditation on its many troubles and a celebration of its vibrant life.

The Bern Book is a first-person story, much closer to direct autobiography than to its fictional refraction. It is an intense, inward-focused account of a young man frequently under duress, full of self-doubt as a writer and a thinker, a Black man in a white town where the people have rarely, if ever, seen one before. Carter is an attentive observer, reflecting on himself as he engages with the locals, exhibiting all the ambivalence of a “stranger in a village.” As time goes by, he vacillates about whether he is still a traveler, already an immigrant, or simply an expat. Locating himself in Bern is a constant negotiation and triangulation, with issues of race always present. While Bern may be no more or less racist than much of Europe was at midcentury, Carter gets noticed, and it troubles him. At one point in the book, he literally screams that “EVERYBODY, Men, Women, Children, Dogs, Cats, and Other Animals, Wild and Domestic, Looked at Me—ALL the Time!” The passage makes up a chapter all by itself.

His initial travel funds exhausted, Carter the narrator finds himself down and out in Bern. He rents cheap attic rooms where he can’t seem to work, so instead he writes in public spaces—cafés, tearooms, the pubs of the old city, the Casino, the Rendezvous, the Mövenpick, and others that are mostly still in existence today. It’s here where he meets people, to whom he tells stories in exchange for a cup of coffee or a glass of wine. He narrates to gain clarity about his own thoughts and feelings, creating that “record of a voyage of the mind,” but he also feels the constant need to justify his existence as a writer—if not his existence, period. The first 50-some pages of the book take the shape of a frame novella, the storyteller engaging with his audience through tales embedded in the context of their telling, the format of putative orality. This dialogic mode continues throughout the book, later becoming more interiorized. His listeners sometimes agree with but also often challenge the narrator—usually via the deeply unanswerable, in fact “Foundation-Shattering Question”: “Why did you come to Bern?”

It is a valid question. As noted, Paris was Carter’s original destination, at the time the center of a Black American intellectual diaspora, comprising Richard Wright, James Baldwin, William Gardner Smith, and others. Despite their different approaches, both The Bern Book and Baldwin’s “Stranger in the Village” essay pose a similar challenge to the hegemonic European discourse on race; in Gianna Zocco’s words, they are “precursors within the Black literary tradition of provincialising Europe ‘from the inside.’” Yet their accounts also radically diverge. Whereas’ Baldwin transforms his experience of the anachronistic, almost naive racism in the Swiss mountain village of Leukerbad into a historically conceptualized reading of racism in the United States and beyond, Carter keeps his story personal, and thus never quite transcends its specific Swiss (or Bernese) context. Carter’s is a story in the flesh, the notes of a living body struggling against both external obstacles and internal hauntings.

Darryl Pinckney is right to see Carter as “that familiar, defensive figure in the café, the man who refuses to be practical, the artist with impossibly high standards, the stranger who is difficult to help.” Jesse McCarthy offers a similar critique in the preface to the 2020 edition of The Bern Book, noting that what makes the book challenging “is the troubling oscillation between sly humor and genuine melancholy” that permeates Carter’s early life and writing, with exasperation at times threatening the narrator’s equanimity. Lottman had called the book “this century’s Anatomy of Melancholy.”

Yet Carter’s fine ear hears in the question “Why did you come to Bern?” not only a challenge to himself but also the locals’ surprise that someone so seemingly exotic should choose to settle in their city. This surprise shades into insecurity, a tacit awareness of their own provinciality. It’s a Swiss mindset that combines the innocence of smallness and insignificance with righteousness and defiance—a kind of inverse sense of superiority that insists, with a streak of resentment, on unrecognized, underappreciated greatness. Carter rarely touches on this subject in his (fictionalized) conversations, but the insight deeply permeates the later parts of the book, which include his musings on Swiss art and culture. Carter has an exquisite sense for hidden tensions—and for obvious discrepancies too. “Switzerland is a man’s world,” he opines in a late chapter, proclaiming the Swiss woman to be “usually more sensitive than her man, not because she is a woman, but for the same reasons that minority groups are usually more sensitive than majority groups, because their sensitivity is their principal means of survival.” This telling observation about gender norms and hierarchies is also a displaced reflection on race and his own situation.

Indeed, the issue of race is omnipresent, in encounters with random people and acquaintances, children and their parents, possible landlords, women, the clientele in the popular tearooms (a social scene he knows well and brilliantly analyzes), even among theater people, or publishers, or the staff of Radio Bern. His radio work gives him a chance to share his impressions of the city in a program that blends text and music, Negro spirituals and the blues. “Everyone was enthusiastic,” Carter writes, getting his hopes up. But when he tries to move away from gospel music and the image of Black people as “the suppressed but happy, suffering but profoundly religious Negro; a relatively primitive, simple-minded creature,” his colleagues respond that, “if we have a [German N-word] writing material for us, we want things which are typical of him and of his people.” And when Carter inquires “into the nature of the ‘typical’ Negro,” they refer him to “spirituals, which were written two hundred years ago.” Carter dryly notes: “Now, as I was the first American Negro most of them had ever seen, much less spoken to, I was astounded that they knew so much about the ‘deepest sentiments’ of the Negro people.” Carter would much rather have played Marian Anderson, a classically trained Black opera pioneer, short-circuiting the automatic attribution of identitarian musical preferences in favor of a transracial embrace of fine art.

The contrast between both of Carter’s books suggests that, after his initial encounter with the white world of Bern—the intensity of his emotions and reactions, the astonishment about local customs, the difficult process of acculturation—Carter needed to take a break, to step back into the settings of his childhood and youth, now far away both spatially and temporally, and thus available to be revisited with a tinge of nostalgia, as a more familiar, though far from idyllic, world in which to live. Such Sweet Thunder is a hometown retrospective that (re)creates a familiar, emotional community as a counterpoint to the author’s contemporaneous intellectual pulse-taking of a foreign city. Such Sweet Thunder depicts a Black community, while The Bern Book shows the effort of building community tout court. The former text is warm, sensual, immediate, multivoiced; the latter cooler, self-reflective, more tenuously connected by still-unfolding human bonds.

The Bern Book covers Carter’s first years in Bern, the most difficult ones. He settled in, made friends, learned both German and Bernese. Already in these early years, he was impressively attuned to Swiss culture and the challenges that art and artists face in this pragmatic country, where “insurance” and “control” are “the most important words in the Swiss vocabulary.” The Bern Book is unique in Black American writing and certainly in Swiss literature too.

Carter largely abandoned writing in the early 1960s; it had never provided an income anyway. He supported himself by teaching English, along with pursuing some radio and theater work. In later years, he increasingly turned toward spiritualism while creatively embracing a new medium: drawing. This part of his oeuvre, which has enjoyed a couple of recent exhibits in Switzerland, is completely unknown in his home country. It is astounding work, luminous and beautiful.

Carter died of esophageal cancer, which, though diagnosed, he did not treat. The Swiss Literary Archives are currently in conversations to acquire his estate, which would cement the transatlantic transplantation of this American original.