For anyone prone to experiencing secondhand embarrassment, there’s a scene in Molly Roden Winter’s debut, “More: A Memoir of Open Marriage,” that should come with a warning.

Winter is at her home in Brooklyn. She has just had sex with her boyfriend while her two children sleep upstairs. Her husband, Stewart, consented to her tryst, but feeling guilty, she dashes naked into the kitchen to text him: Don’t worry, she writes, “he has nothing on you as a lover.” But instead of texting her husband, she accidentally sends the message to her boyfriend, who leaves in a huff, and later breaks up with her. Winter, devastated, begs her husband to come home to comfort her.

“I still get a little nauseous thinking about it,” said Winter, 51, who was sipping tea in the living room of her bright and airy townhouse in Park Slope, Brooklyn. “Talk about the cringiest, cringiest, most awful thing that could happen.”

It’s far from the only agonizing and breathtakingly candid scene in “More,” which documents Winter’s often turbulent experience of open marriage — the resentment and jealousy she felt toward her husband’s girlfriends, the flashes of guilt and shame, and the challenges of juggling her obligations as a wife and mother with her pursuit of sexual and romantic fulfillment.

Winter is keenly aware that people may judge her for the behavior she describes in “More.” But she also said she felt compelled to write about her experience, in part because she felt that non-monogamy is so often depicted as something happening on the fringes, not as a lifestyle that married moms pursue.

“I felt like there were no stories from the mainstream about it, and I felt very closeted,” Winter said. “It often feels like mothers are not supposed to be sexual beings.”

“More,” which Doubleday will release on Jan. 16, is landing at a moment when polyamory is drifting from the margins to the mainstream. About a third of Americans surveyed in a YouGov poll in February of 2023 said they preferred some form of non-monogamy in relationships.

Along with novels, TV shows and movies that depict throuples, polycules and other permutations of open relationships, there is a growing body of nonfiction literature that explores the ethics and logistical hurdles of polyamory. Recent titles include memoirs like the journalist Rachel Krantz’s 2022 book “Open: An Uncensored Memoir of Love, Liberation, and Non-Monogamy,” and self-help and inspirational books like “The Anxious Person’s Guide to Non-Monogamy,” “The Polyamory Paradox” and “A Polyamory Devotional,” which has 365 daily reflections for the polyamorous.

Jessica Fern, a psychotherapist who counsels people in open relationships, said Winter’s account adds a new layer to the growing catalog of nonfiction about polyamory.

“Her story, which is about what it means for a mother to be erotically charged, that story I haven’t seen enough yet,” said Fern, author of “Polysecure” and “Polywise.”

Fern noted that there might be a scarcity of books by moms in open marriages because they are simply too busy: “When you’re a parent and you’re polyamorous, who has time to write?”

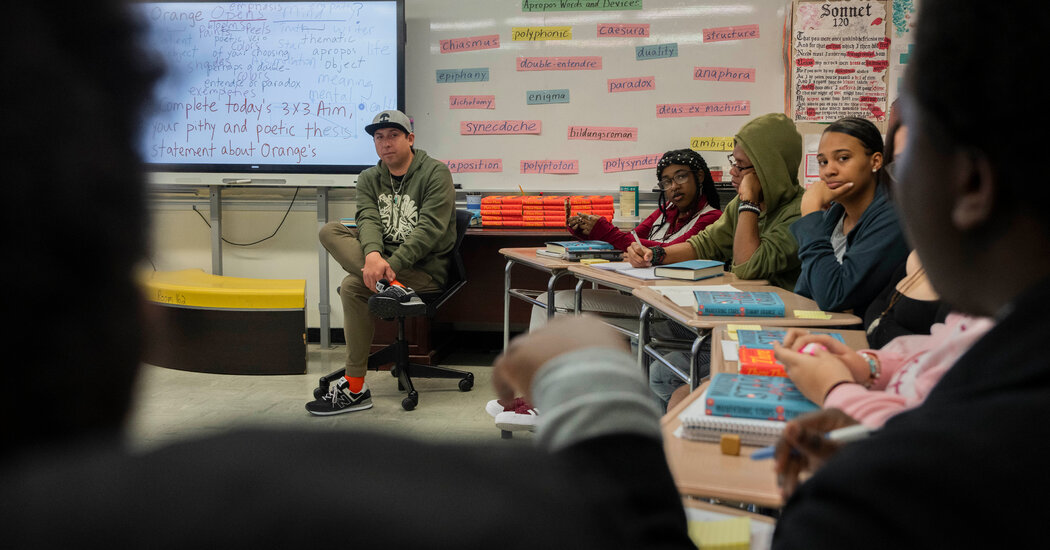

Winter concedes that polyamory could be exhausting — particularly when she had to balance it with marriage, child care and working as an 8th grade English teacher.

“I did not sleep very much,” she said.

Opening the marriage wasn’t just about doing whatever — and whoever — she wanted, she said. She had to cast off internalized sexism and her tendency to put others’ needs before her own, issues she worked through in therapy. What began as sexual thrill-seeking led unexpectedly to self-discovery.

“I thought non-monogamy was going to be all about the sex,” she said. “I thought I was going on a big sexual adventure, and it was going to be super exciting. And it was, until it wasn’t.”

To be clear: “More” is also about the sex. Winter recounts her experiments with butt plugs, fisting and anal intercourse, and catalogs her extramarital relationships — which range from brief encounters in seedy hotel rooms to romantic partnerships that last for years — in meticulous detail. She changed the names of her and her husband’s respective partners to protect their privacy, but often leaves little else to the imagination.

There’s “Karl,” the generous German lover who seems intent on pleasing her in bed, then pushes her to have a threesome with him and his fiancé, then ghosts her. There’s “Laurent,” the French-Argentine lover who refuses to wear condoms and likes to have sex in public restrooms and co-working spaces — a fetish that gets Winter banned for life from a shared office space.

And there’s “Jay,” a 29-year-old with a shockingly large penis. After they have unsatisfying sex, Jay tells Winter he usually can’t orgasm from intercourse, but that he plans to masturbate to the memory of her. “You’re sweet,” she tells him.

Winter grew up in Evanston, Ill., and was in her early 20s when she met Stewart Winter, the man she would marry. He made her laugh and was passionate about his work composing music for TV shows and movies.

In 2008, they had been married for nearly a decade and had two young sons when Winter met someone else. Frustrated after an exhausting day caring for their boys while he worked late, she took a walk one evening. A friend invited her to drinks, and at the bar she fell into a flirtatious conversation with a man.

When she told her husband later, to her surprise, he wasn’t mad. Instead, he urged her to sleep with her new acquaintance, and share the details.

After Winter started dating, it wasn’t long before Stewart also started seeing other women. Though she agreed it was only fair, she was consumed by jealousy and occasionally asked to close the marriage.

Stewart confirmed that open marriage was easier for him at first.

“Molly might have been more discerning than I was at that point,” he said, comparing his dating experience to being “at a salad bar.”

In the early years, many of her sexual exploits proved unsatisfying. At the time, most online dating sites didn’t cater to polyamorous people, so she sometimes resorted to dating men who were cheating on their wives and girlfriends. “Not my finest hour,” she said.

Some of her closest friends worried that she was sabotaging her marriage and that she would get hurt.

“I worried that she was leaning so heavily into the sex part that she was not really thinking about the emotional element,” said Rebecca Morrissey, a friend of more than 25 years, who added that her concerns faded when Winter started forming healthier relationships with her paramours.

Eventually, Winter swore off men who were cheating and began seeing people who were also in open relationships, a demographic that became easier to find when online dating services added non-monogamous to their menus. Even then, options were limited.

“There were so few people that I kept getting paired with Stewart,” she said.

Winter and her husband struggled with when and how to tell their sons about their arrangement, and wanted to wait until their children were mature enough to handle it. That plan failed when their oldest son, then 13, saw his dad’s online dating profile on his laptop, and texted his mother in a panic, asking if they were in an open marriage. Her youngest son found out in a similar way a few years ago, when he was 14, she said.

By now, her sons, who are 19 and 21, are blasé about their parents’ sex lives. Her oldest has read her book, and told Winter he skipped some of the “nitty-gritty” sex scenes, while her youngest chose not to read it, she said.

It took a few years before Winter felt comfortable revealing the details of her open marriage to a larger circle of friends and family.

When she told her mother about her adventures in non-monogamy, she learned more about how her parents, who have been married for nearly 60 years, also had an open marriage.

Her parents, Mary and Philip Roden, were a bit uncomfortable with the intimate details their daughter shares in her memoir, but ultimately endorsed the book, they said in a video interview.

“For the most part, I totally approved of what she was saying,” Mary Roden said, though she noted that she was put off by “the raw sexual detailed descriptions.”

For his part, Stewart is enthusiastic about the memoir, but worries that people will think he manipulated his wife into opening their marriage.

“All my reservations, to be perfectly honest, are because I’m being selfish, wondering, how is this going to make me look?” he said.

“More” ends in 2018, when Winter’s boyfriend, whose wife had recently divorced him, broke up with her after she turned down his ultimatum to end her own marriage. Winter was heartbroken, but moved on, and has had other serious romances since.

She’s grown more confident that her marriage of 24 years has benefited from their outside relationships. She’s mulling another book about her open marriage — which will in part explore the surprising connections she’s formed with the “other women” in her life, including Stewart’s girlfriends and the wives of the men she dates.

For now, Winter is bracing herself for the impact the book will inevitably have on her and those around her — but she seemed undaunted.

“I’ve been spending a lot of my time calming everybody else down,” she said. “This doesn’t feel like something I need to be afraid of.”