In 1982 Austrian-born art dealer Thaddaeus Ropac was in his early 20s, and still looking for direction. Though he had no ties to the art world, he landed a job installing 7000 Oaks, a work by German conceptual artist Joseph Beuys that involved planting said oak trees, for the seventh edition of Documenta in Kassel. For Ropac, the proximity to Beuys, whose heady work had long elicited a cult following, was transformative. Ropac looked to Beuys’s work as a guide for the kinds of artists he wanted to follow.

“For me, he changed everything. I was a total follower of his theories, of his conceptual ideas,” Ropac told ARTnews.

A year later, in 1983, Ropac set out to launch his own gallery in Salzburg, located, he said, “on the wrong side of town.” While the Austrian city still buzzed in the summer as other parts of Europe shut down for the season, it wasn’t art focused. “It was totally dominated by music,” he said.

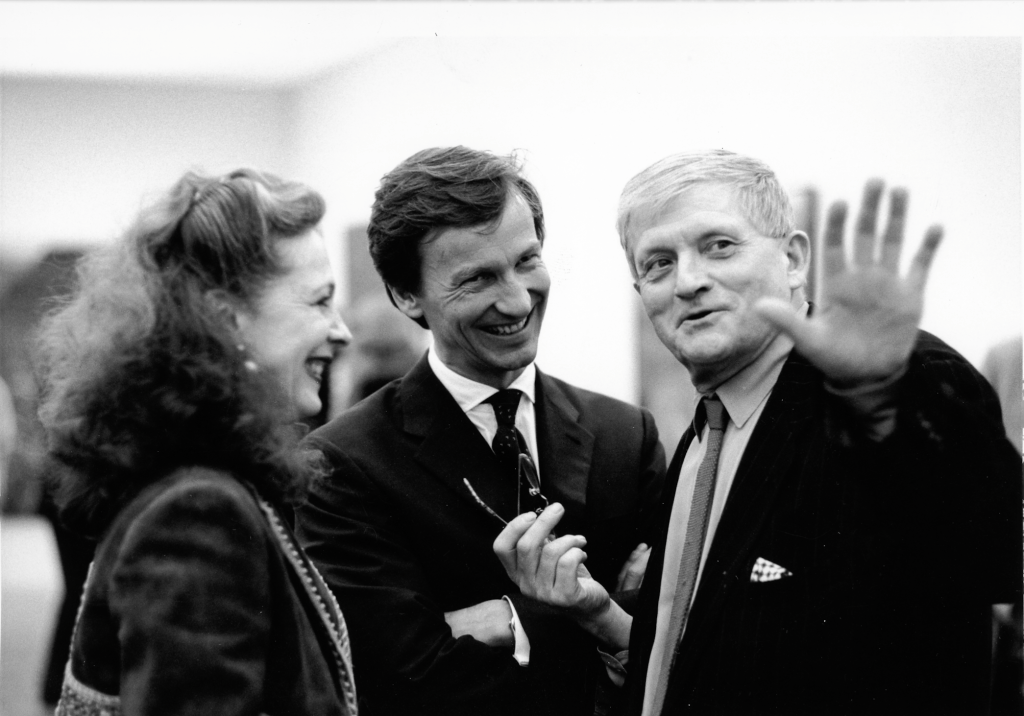

Now, at the age of 63, Ropac isn’t pining for the old days. He’s more interested in answering bigger questions about how to continue to serve the artists he’s been cultivating for four decades. He considers how to promote artists in a market that’s grown into a behemoth since he first entered it. While Ropac has signed up, and held on to, some of the most prominent names in the game, he said his roster’s range is a product of instinct rather than calculation.

ARTnews caught up with Ropac on the eve of his 40-year anniversary exhibition, which spans the works of 70 artists across his two Salzburg locations and runs until the end of September.

(This interview has been edited lightly for clarity and concision.)

ARTnews: Tell me a little bit about your gallery’s origin in Salzburg and what the scene was like when it opened.

I had my big eureka moment with an installation of Joseph Beuys in Vienna, Basic Room Wet Laundry (1979). It was irritating and kind of shocking. It was when I really started to become aware of contemporary art. Then I started to think of organizing exhibitions with friends, but more like an artist space, because I still felt the calling of maybe being an artist myself. Nineteen eighty-two was this incredible year. There was an exhibition in Berlin, which was called “Zeitgeist” curated by Norman Rosenthal in the center of Berlin’s Martin-Gropius-Bau, in a courtyard. Rosenthal at the time invited all these incredible international artists to be part of it. When I left Berlin in 1982, I had my wish list.

AN: So when was the turning point?

I wanted to go back to Austria and just open a gallery and show some of these artists that I discovered while in Germany, and my first idea was Vienna, but somehow, I didn’t really connect with Vienna. I found a book that the Austrian author Oskar Kokoschka wrote called the School of Seeing. He opened the academy in Salzburg just for the summer for two months every year in 1953. He kind of declared a very open Academy where you don’t need to bring in your work to be accepted.

AN: The gallery’s roster has around 60 artists, and it feels wide-ranging in terms of art historical influences. You represent younger artists who focus on technology like Cory Arcangel to less commercial cult figures like Valie Export, as well as the Rauschenberg estate. Tell me about how you shaped the roster after all these years.

I was very taken by American art. That’s the reason I wanted to meet Warhol, and I met Rauschenberg and … then-younger artists, like Basquiat, who I had three shows with during his lifetime. On the other hand, I always knew it would be German and Austrian art. I think it was done a lot by instinct. At least, I had to have the feeling that I somehow understood the work. I always picked the artists I had a fascination for.

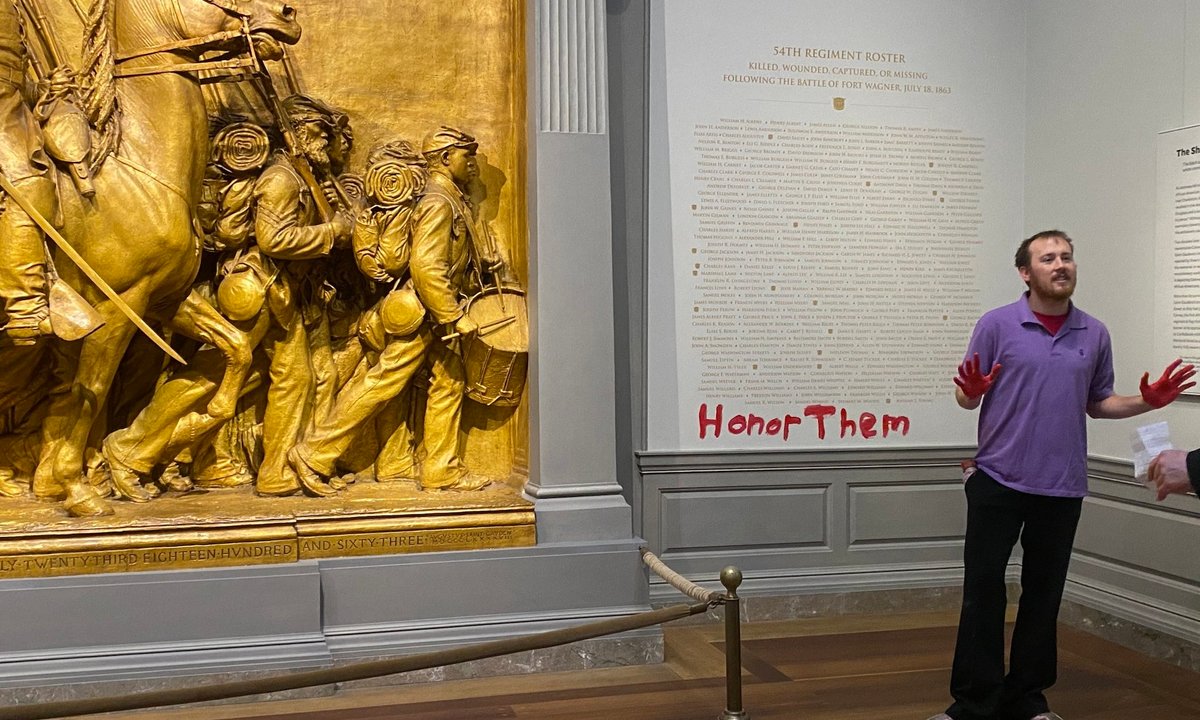

Installation view of 40th anniversary exhibition at Thaddaeus Ropac in Salzburg.

ULRICH GHEZZI

AN: You started to develop alongside[NES1] some of these artists.

[Georg] Baselitz was the longest[NES2] . I had my first exhibition in 1984 and then with Baselitz, just a drawing show in 1986. I was still too young. The gallery was too small. But then from the ’90s on, we really started working together.

AN: How did things progress? You expanded to Paris, where some of the artists were already represented.

I became … for many of these artists a gallery to really work very intensely together with. They started to take me seriously. This was a process of the first 10 years where I was trying to get my footing. I opened in Paris because after a while, Salzburg felt like a small town. It was outside the summer season, and artists expected that audience. I didn’t want to go to Vienna or Berlin, because I felt I was already here in the German context. Paris was just, for me, the right place to move, but also really to get closer even to the artists.

AN: The business was very different back then.

Back then the market was not so relevant. You know, artists didn’t even expect that you sell a lot, you could not even disappoint them.

AN: The gallery represents a few major artists’ estates, among them Elaine Sturtevant and Donald Judd, that gives the roster this kind of institutional edge. Tell me about how some of the relationships formed with artists that led to these representations.

Sturtevant for example, I met her in the 1980s in New York. She moved to Paris and I worked with her until the end of her life; it was almost natural that we would work with the estate. Beuys of course was the one artist I admired so much. I felt very honored when they decided to work with us. The only artist estate we represent now [with which] we hadn’t really had a personal relationship was Donald Judd. You know, for me, minimalism is one of these movements that were entirely invented [in] America. This really is the movement, in my view, which added the most American flavor to what happened in the late part of the 20th century.

AN: You manage a much bigger team now. The market has changed drastically. Your business has expanded to Seoul. Was expansion always the goal?

Expansion, it’s not a necessity, but it’s a possibility. So because you want to give your artists the best infrastructure, you want to give them the best possible representation. It’s a bit of a race also, I have to say, especially in Asia. For me, to expand in Europe was somehow natural, to go from Salzburg to Paris, because we felt we can really give our artists the best possible service in Europe.

AN: So to grow is more about considering new audiences?

I don’t feel I do it because I need to do it and we need to grow. I think it gives you different horizons into an entirely different audience. It’s not necessarily the business which comes from it, it’s more to kind of keep the artistic side up with some new challenges, because we have to develop the program. But we also need to understand a different cultural environment. The strongest exchange I felt in Asia was really in Korea. I feel there’s a level of sophistication [there that] is almost unparalleled. I go to collectors’ homes there and … see a Judd sculpture, and when I ask them when they acquired it, [they say] they bought it in the ’80s, just when it was produced. It’s exciting to be there.

VALIE EXPORT, Syntagma (1983).

AN: Building new audiences in Asia has its challenges.

There are more risks involved. It’s sometimes also the Wild West. It’s more about how to come to a different culture with the right respect. How do you understand an artwork? America and Europe grew to get better in the art world very closely. In Korea, artists were not always impressed by Europe and America. They developed their own language early on, in the avant garde, in the 1950s and 1960s, where they maybe looked to Japan a bit, but otherwise they developed their own language. You have such very different starting points.

AN: The business is much larger now. It changed a lot.

When I started, there was America and there was Europe, and the European artists wanted to be shown in America, and American artists, in Europe. It was very insular. People didn’t look to Latin America or to Asia. But this show in Paris, Magiciens de la terre, at the Pompidou Center in 1989 did. And for me, it was one of these few shows … that became mentoring what I wanted to do. You had artists from Pakistan and Korea, and I remember I saw this artist Lee Bul from Korea in the early ’90s. You know, I contacted her and then we started to work together. All these steps were done really [because I was] fascinated by an artist’s work and just want[ed] to go into this artist’s universe.

AN: Are there any parts of the art world today you’re skeptical of?

The level of speculation [that] entered the market, I would have never thought this would be possible. We had to learn to be so careful how we are placing the work, and it also became difficult. I don’t want to undermine the importance of art fairs in what we do. But this speed also is dangerous because it can build careers so fast and it can also blow careers, because maybe there’s too much pressure on the artist. Often, we have to think how we do this so there aren’t these victims of the speed of the market.