It’s easy to write about Hiroshi Nagai’s paintings when the sun is shining. Nagai is a poet of summers past – the blue-sky days, sure, but also the rosy dusks and those nights where you step outside and the air feels perfectly still. I found out about Nagai while scrolling TikTok recently. His precisely rendered images flashed up before me and I instantly lost the grasp of whatever else I was thinking at the time. Nagai’s work took me off to this nostalgic world of peachy sunsets and palms and strange urban beaches. Who is this? Why did this stuff create tingles in the videogame part of my brain? Maybe Nagai simply reminded me of OutRun – OutRun but also Hockney.

Later that day I looked Nagai up and discovered that he did in fact exist outside of TikTok. Born in 1947, Nagai wanted to go to art school, inspired by his father’s oil paintings. According to a great piece I read on Tokyo Cowboy, Nagai was unable to get a place on a course and instead worked for a set decorator in Tokyo before his own career took off. Thanks to his prolific creation of album covers, his work eventually became a visual signature for the Japanese City Pop movement of the 1970s and ’80s – a movement that blended everything from funk, disco and soft rock to create shimmering cinematic confections with an “urban feel”.

Nagai’s been haunting me a bit since that first TikTok. I can’t stop rewatching it and digging around for his stuff on eBay. I can’t stop browsing his prints on places like Etsy. To fully get the Nagai experience, yesterday I took an hour to put on a City Pop playlist and lay back on the sofa just out of the sun, scrolling through his paintings on my phone.

City Pop is the magic ingredient to an appreciation of Nagai’s work, I reckon. It’s glittering and synthy, with bouncy piano breaks, the steady taut slap of drums, and much crooning. You’ll get the tight snarl and squeal of a guitar, but no one element ever dominates. Everything in the song feels held in a careful tension. It’s slick and artificial, and that’s the point. It feels like bingeing Moonlighting, or like going out at night in a cool old car and being a detective. You want to visit bars, but only hotel bars. You want to live in apartments on the second floor, with those slatted blinds in the windows and nothing much beyond margarita mix in the kitchen.

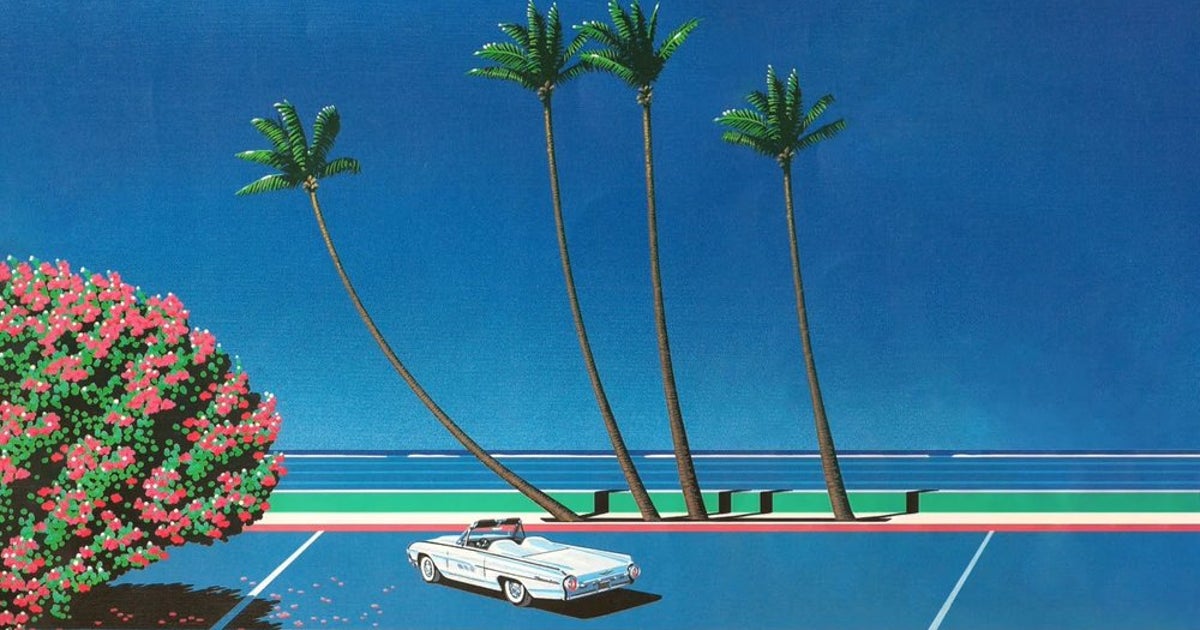

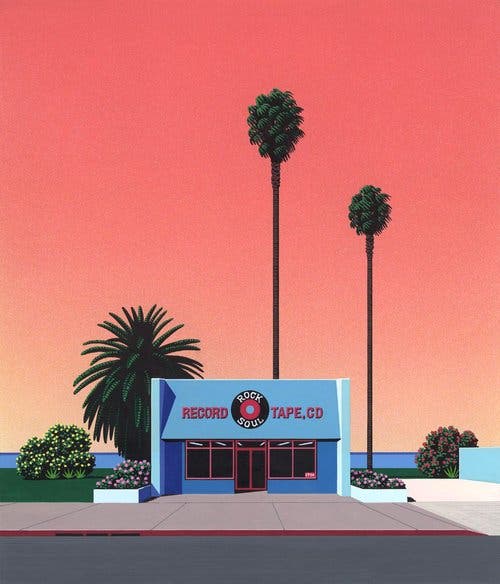

There’s a lot of this to Nagai’s imagery. Cityscapes, poolsides, beaches. They’re spaces that have been largely stripped of people, places where the buildings are always at a polite distance, mid-century hills houses held back by a pool, or a skyline rising beyond a bridge and a bay. Only water’s really allowed to get close to the viewer. Sometimes there’ll be a car or a plane or words written on a shop – RECORDS, TAPES, CDs – but almost never anybody around. Red lights on the corners of skyscrapers, perfect game boards of lit midnight windows. In one picture there’s a towel on a lounger and the human presence it suggests is almost a shock after all that absence. But it’s just a towel. It’s still absence. It’s still Nagai being Nagai.

Where is all this? California? Japan? It’s hard to tell, but a lot of Nagai pictures have distinct aspects of both places. The bridge in one will remind me of an overpass I once walked by near Konami’s offices in Tokyo, while a cool grey sidewalk with manicured plant beds in another will tell me: Santa Monica. Similarly, I couldn’t place these images in an era, unless there’s a Learjet in the frame or a sports car. Most of them feel a bit like the 1950s, but the 1950s in the way it was repeatedly invoked in the 1980s. Wayfarers, then, but they’re Tom Cruise’s Wayfarers.

The thing is, I ask these questions because I love these spaces. Nagai’s work really speaks to me. And I feel like they’re videogame spaces he’s creating, not just because of the emptiness, the angularity, the pixely detail. They feel, like videogame spaces, as if they have been treasured during their creations, almost wished into being, each aspect carefully placed, each skyline working to underline a mood. M. John Harrison calls a certain kind of space that a person returns to again and again for some need they can’t quite put into words (that’s my gloss not his) a “dream estate”. Nagai’s paintings are all dream estates for me.

Here’s something that has bugged me the more I have looked at these images – and it’s a strain of question one often asks of videogames too. How are they done? I go online and it seems to be a big question others have about Nagai’s work. They’re called paintings, but they often look like they’ve been pixelled together, or even clipped together from those little plastic jewels you can buy in craft shops. Yesterday I moved in close on a Nagai landscape – they’re all landscapes – and saw that a tree was edged in these tweedy little tongues of green, which reminds me, jarringly, of someone like Rousseau. Elsewhere I discovered that little rounds of lights placed to invoke distant traffic were not uniform. Looking closer at these pictures, actual paint makes a late impression: Nagai’s soaring palms in silhouette actually have rounded, organic edges, while the occasional shard of city light will reveal itself as a watery blob.

I’m writing this on Friday afternoon, after a hot day in which I did two school runs with my daughter. I was early going to pick her up this afternoon, so in search of shade I went to the nearby park and sat on a bench under a tree and looked out across a huge field with some houses visible beyond it. It was hushed in the park, and the bright sun rendered the grass as a series of light, glossy lines, while the distant bushes came together in friendly, rounded clumps.

It’s a busyish place most of the time, but today there was nobody present, nobody but me, and I felt like I was actually in a Nagai painting myself. And it made me realise: these are carefully selected moments he’s painting, as much as they’re carefully crafted spaces. They’re these precious slices of time where things go quiet, a distant plane arcs towards an unseen airport, a car idles outside a record store, and the beauty of the modern world silently makes itself known.