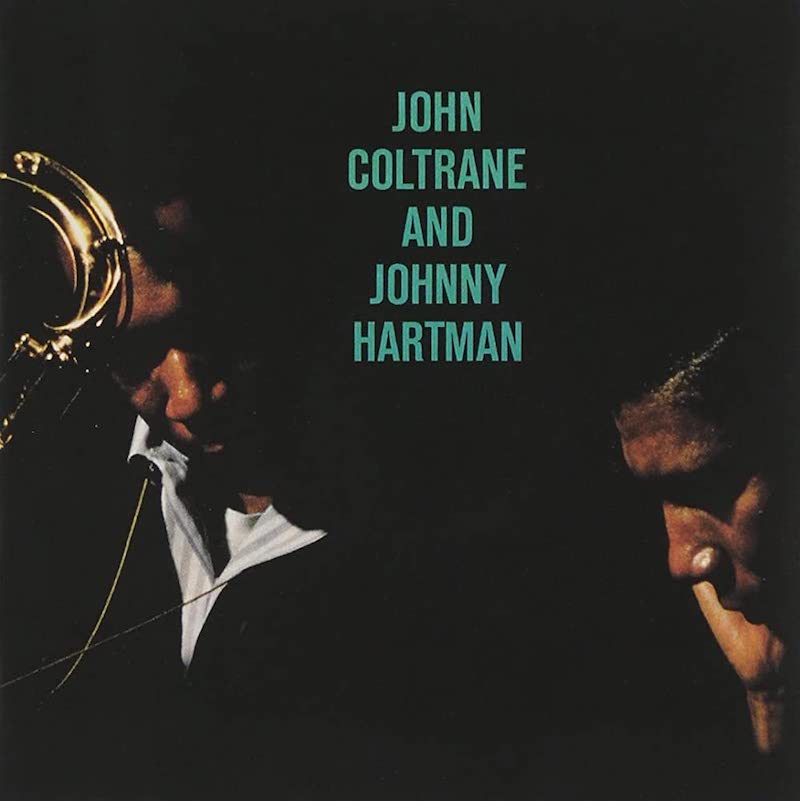

On March 7th, 1963, John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman were in transit to Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. Although the two musicians had never worked together, they’d brushed shoulders in similar circuits: both had shared bills at The Apollo Theater and played in Dizzy Gillespie’s band (although their timeline with Gillespie never overlapped). As the Manhattan skyline receded in their rearview mirror, one could imagine the two crossing over the Hudson River, tapping cigarette ash against the cracked windows, evading pre-session jitters by sharing war stories from gigs with Gillespie, reminiscing about the early days of their careers: the grimy clubs, the ashtray-filled sessions, the endless nights that turned into endless days. After all, these two strangers needed something to discuss to fill the tense air between them. As they got closer and closer to Van Gelder’s studio, both musicians juked and pivoted around the elephant in the car: in just under an hour, a session was to take place that neither had prepared for. Outside of a rough list of jazz standards the two had briefly discussed, they had no charts or prior arrangements worked out.

Furthermore, the forthcoming session was neither Coltrane’s nor Hartman’s idea. The two had been booked together by Bob Thiele, Coltrane’s producer at Impulse Records. Thiele wanted Coltrane to make more commercially viable music after a series of poorly received albums, which had prompted John Tynan of Downbeat Magazine to refer to Coltrane as “anti-jazz” in a 1961 review. Pairing a renowned jazz musician with a vocalist had proven to be a successful formula for album sales in the early sixties, and it’s highly likely that when Thiele pitched the idea of doing a vocal album to Coltrane, he was considering the success of records such as Nancy Wilson/Cannonball Adderley (1962), which rose to the No. 30 position on the Billboard Charts the previous year. Coltrane, who had never recorded with a vocalist before, wasn’t opposed to Thiele’s proposition, but he had a few stipulations: he would choose which singer he worked with as well as the backing band, which included Coltrane’s wrecking crew of McCoy Tyner (piano), Jimmy Garrison (bass), and Elvin Jones (drums).

In a 1966 interview with Frank Kofsky, Coltrane explained why he selected – of all singers to work with – Johnny Hartman as his first pick: “And Johnny Hartman – a man that I’d had stuck up in my mind somewhere – I just felt something about him, you know. I don’t know what it was. And I liked his sound; I thought there was something there I had to hear, you know, so I looked him up.” Coltrane was familiar with Hartman’s debut release for Bethlehem Records, Songs From The Heart (1956). Featuring a quartet led by trumpeter Howard McGhee, Songs From The Heart introduced the world to Hartman’s romantic baritone. It also showcased his cool composure and penchant for restraint – when to dip out of the arrangement and let the band take over. This approach caught Coltrane’s ear given his preference for playing lead melodies high on the range of the tenor saxophone, often occupying the space where a singer would take the lead. Hartman was not only a vocalist that spoke Coltrane’s musical language, but one he could share the spotlight with.

Initially, Hartman was reluctant to accept Thiele’s offer to record with Coltrane. At forty years old, Hartman had just begun garnishing recognition as a stand-alone act after decades of being a sideman for the likes of Earl Hines, Erroll Garner, and Dizzy Gillespie. With solo records for Bethlehem and Roost already underneath his belt, the idea of recording with Coltrane was seemingly a step backward in a career path that had just started to come to fruition. And although Coltrane was already a behemoth figure in the jazz scene, far more successful and admired than Hartman, he was also known as a wild man. Before Coltrane was Coltrane, he was a horn for hire – and a near-perfect one at that, changing to tenor upon request from a historic rolodex of band leaders without batting an eye or hitting a sour note. But Coltrane’s life on the road was rifled with drugs, and he quickly fell into alcoholism and heroin addiction. Coltrane’s drug abuse continued through his 1955 audition for Miles Davis’ band, at which point even Davis had caught wind of Coltrane’s notoriety as “a bad motherfucker.” After Davis fired Coltrane from his band in 1957, Coltrane vowed to kick his heroin habit, using his music and newfound interest in spirituality as a guiding post toward sobriety. Nonetheless, the tawdry tales of debauchery from Coltrane’s checkered past had become jazz folklore by the early sixties, and a reputation proceeded him. To the straight-laced Hartman, Coltrane was a potential loose cannon that could dismantle the budding career he’d worked so hard to build.

“I didn’t know if John could play the kind of stuff I did,” Hartman would later tell jazz writer Frank Kowfsky. “So I was a little reluctant at first.” Personalities aside, Coltrane’s musicality was embedded within the bebop and hard-bop idioms of jazz, which – if they did feature vocals – capitalized on free-form scatting and recasting the melodic interplay of a song. Hartman, a singer who idolized the supper-club balladeer stylings of Perry Como and Bing Crosby, took a traditionalist approach to his music: “There’s nothing you can do with a good song except sing it,” Hartman would say in a 1982 retrospective interview with The New York Times. “I didn’t fit in with bebop, so I just went on doing ballads like ‘I Should Care’ and ‘Old Black Magic.’”

Thiele was persistent despite Hartman’s reservations about recording with Coltrane. Eventually, after much debate, Thiele convinced Hartman to see Coltrane perform at Birdland in Manhattan. Reluctantly, Hartman attended the show, and was admittedly surprised to hear Coltrane’s subdued approach to ballads. Instead of trying to overpower the song, the hard-blowing tenor saxophonist laid back in breath and space, coloring each sparse note with gentle sentimentality: “John was working at Birdland, and he asked me to come down there, and after hearing him play ballads the way he did, man, I said, ‘Hey…beautiful,’” Hartman would recall to Kowfsky. “So that’s how we got together.” That night, after Birdland closed down, Coltrane and Hartman quickly went over some standards together. A week later, Thiele booked the duo at Van Gelder’s studio with Coltrane’s band.

And now here they were, only a few days after meeting each other for the first time, weaving through traffic on the George Washington Bridge, making small talk with each other as they headed towards Van Gelder’s studio: Coltrane, a living legend with a sordid reputation looking to redeem himself in the commercial space, and Hartman, a vocalist skirting past his prime, finally on the cusp of a lucrative career that his wild-card collaborator could potentially jeopardize.

The No. 1 song that day was “Walk Like a Man” by The Four Seasons, and Coltrane and Hartman likely caught Frankie Valli’s cascading falsetto as they scanned the FM dial. Then, between bursts of static and snippets of songs by Dion and Skeeter Davis, the radio signal suddenly caught hold of a familiar voice: Nat King Cole, singing his 1948 rendition of Billy Strayhorn’s classic, “Lush Life.”

“…Where one relaxes on the axis of the wheel of life/To get the feel of life/From jazz and cocktails…”

As Cole’s rich voice filled the car, Hartman reached for the volume knob, turning the song up. According to Will Friedwald’s book, The Great Jazz and Pop Vocal Albums (2017), Hartman then turned to Coltrane, exclaiming, “Man, this is one of the great tunes of all time.” Coltrane agreed, asking, “Do you know it?” Hartman responded that he did, and they decided to try recording the song that day.

After arriving at the Englewood Cliffs studio, where Van Gelder’s two-track tape machine was already humming in anticipation, Coltrane and Hartman told the band about their idea to record “Lush Life.” Coltrane had previously recorded a fourteen-minute-long instrumental version of the song three years earlier for his Prestige album of the same name, Lush Life (1958). The band was familiar enough with the Strayhorn standard to give it a shot, so they agreed to lay down a take. Using the Nat King Cole version they’d heard on the radio just a few minutes earlier as a northern star for tempo and structure, Hartman and Coltrane gave each other a knowing nod as Van Gelder hit the “RECORD” button on the tape machine.

According to a 1982 interview with Hartman for The New York Times, “Lush Life” was the second song they recorded that day: “We did it in one take. We did everything on that album in one take except ‘You Are So Beautiful.’ We had to do two takes on that one because Elvin Jones dropped a drumstick on the first take.” Hartman’s statements were later refuted in 2005 by jazz archivist Barry Kernfeld after he discovered Van Gelder’s raw tapes from the session, which document complete alternate takes for all six songs, described by Kernfeld as “absolutely riveting” (these tapes have never been released due to ownership discrepancies between Coltrane’s estate and Universal Music). What is known for sure is that the six songs that make up the track-listing for John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman (1963) were recorded in a single session. Unbeknownst to the studio personnel at the time, when Coltrane and Hartman drove off from Englewood Cliffs the night of March 7th, 1963, they left behind a slice of jazz history on Van Gelder’s tape machine.

The songs that make up John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman – “They Say It’s Wonderful,” “Dedicated To You,” “My One And Only Love,” “Lush Life,” “You Are Too Beautiful,” and “Autumn Serenade” – were already standards by 1963, and have since been recorded ad nauseam by a plethora of jazz artists throughout the decades. Yet many consider the definitive versions of these songs to be the Coltrane and Hartman renditions. Hartman’s satin croon and Coltrane’s pining sax elevate the emotional resonance of each composition without sacrificing the original intent. Coupled with the tender accompaniment from Tyner, Garrison, and Jones, these songs have never been as intimate or powerful as they are on Coltrane and Hartman. At its most transcendent, the delicate change from Hartman’s voice to Coltrane’s sax is hardly noticeable.

Out of the many serendipitous occurrences that brought forth Coltrane and Hartman, perhaps the most is the decision to record “Lush Life,” an impromptu idea that occurred out of the right song being on the right station at the right time, moments before Coltrane and Hartman arrived at the studio. Apart from literally being in the middle of the album, “Lush Life” serves as the record’s thematic and tonal centerpiece. It’s a song that encapsulates the bittersweet atmosphere throughout Coltrane and Hartman, showcasing all its hallmarks: Hartman’s impeccably smooth enunciation, Coltrane’s soulful sax, Tyner’s relaxed keys, and the self-effacing rhythms of Garrison and Jones. Lyrically, the song is about a jazz-cat reflecting on lost loves and past regrets, a self-portrait of despair, doused in one too many late nights and stiff cocktails: “Life is lonely again/And only last year everything seemed so sure/Now life is awful again/A troughful of hearts could only be a bore.“

Hartman’s vocals on “Lush Life” are utterly convincing. Languid and casually tragic, Hartman is the perfect conduit to deliver the song’s lovelorn grievances. He embodies the role of the dejected playboy so definitively that one can only assume Billy Strayhorn had Hartman in mind when he wrote it in 1936 (considering the song’s worldly sadness, it’s astounding that Strayhorn wrote “Lush Life” when he was only sixteen years old. In a self-fulfilling prophecy, Strayhorn’s words as a teenager predicted the life he would eventually lead, becoming a well-traveled socialite and depressed alcoholic). More so than any other song on Coltrane and Hartman, “Lush Life” displays Hartman’s vast emotional vernacular. It’s a song that has to be lived-in to translate properly: the anguish and loneliness cannot just be performed, but authentically felt. It’s a song that gave Frank Sinatra a hard enough time that when he tried to record in 1958, he gave up. Sinatra laughed it off, saying he would “put it aside for about a year.” He never returned to it.

Where Hartman’s vocals end on “Lush Life,” Coltrane’s musicality begins, echoing the lyrical sorrow in the form of a dark-tinted solo, crestfallen and aching. In the liner notes for Coltrane and Hartman, A.B. Spellman expounds on this by writing, “‘Lush Life,’ which Coltrane’s recorded before, is often performed but never this well. Hartman’s vocal control lets him handle the songspiel of the first stanza in a way that seems like pure communication. From there, he glides through the difficult changes of a very wordy song with an ease of expression that pulls every nuance from it with no ostentation whatsoever. And Hartman, like Coltrane, uses Tyner’s comping as an extension of his expression and as a musical ancillary to a conversational song. Coltrane’s solos – well, another insight into what the song is about. A double-timed commentary in what Hartman’s just said.”

The call and response between Hartman’s buttery baritone and Coltrane’s midnight sax – the often trepidatious balancing act between words and music – is the key to Coltrane and Hartman. There is never a moment where one is stepping on the other’s toes or overstaying his welcome. Instead, their musical partnership is perfectly in sync, respectful and spacious, allowing each other to embellish without lingering. It recalls the collaborative ease of a duo performing together for years, or at least far longer than a few hours during a single session.

Coltrane would never record with another singer; Coltrane and Hartman is his only vocal album. For Hartman, the collaboration with Coltrane would become the highlight of his discography, and “Lush Life” the most requested song of his career.

Coltrane and Hartman is essential listening not just for jazz aficionados, but hopeless romantics far and wide. The smokey mood of the record eclipses its genre, belonging more to an ethereal wavelength of nocturnal ambiance than musical categorization. It’s a record for the half-empty hours after last-call, when chairs are stacked up onto cocktail tables and ashtrays are emptied, when the neon sign above the door clicks off, leaving only the blue hue of the moon to light the way to the next after-hours bar, to commiserate in drunken misery with other wayward night owls and vagabond souls. Or as Hartman sings in “Lush Life:” “I’ll live a lush life in some small dive/And there I’ll be while I rot with the rest/Of those whose lives are lonely too.” | e hehr

For heads, by heads. Aquarium Drunkard is powered by its patrons. Keep the servers humming and help us continue doing it by pledging your support via our Patreon page.