During a triptych of alternate versions and demos appended to Spilt Milk for this reissue, Styvers at last plays the piano on some of these songs. She is less exacting than Parker, but there’s modest charm to her touch, a sense that these sentiments needn’t be browbeaten. When Styvers is in charge of telling her own story, you can get closer to it, feel that it’s hers. How might Spilt Milk have taken shape had Styvers and not a series of hired men been behind the keyboard and mixing board, had she taken charge of these sessions like the audacious Judee Sill, a California contemporary who also made two early albums for a big label and then vanished?

Styvers did manage to commandeer the piano for much of her second and final album, The Colorado Kid, ceding the seat to Parker only three times. And there’s only one co-write with Murphy. This burgeoning resolve creeps into every element of these 11 songs, like a vine that’s finally found what it needs to sprout and spread. If Spilt Milk was Styvers sorting through the damage and delight of her past, on The Colorado Kid, she was digging into the present while cautiously turning toward her future, saying plainly what she might want and need there—particularly, a dependable partner invested in an equal emotional give-and-take.

The insistent and bewitching “Take Me Into Your Arms Again” is a plea for permanent forgiveness, as she works to cut ties with her libertine history. “White Flowers”—Styvers’ incredible parable of blooming after the fire, beginning meekly and exploding into a massive chorus—is a parallel devotional. She turns away from “the bodies of men you don’t even know about.” Later, she even makes demands for herself: “Come stay with me for a few weeks,” she sings, her voice cool and assured in this new role of authority. “I’ll get you to mean what I want you to mean.”

The arrangements, too, are newly daring. Howling saxophones flirt with dissonance toward the end of “There’s Still Time (Follow Your Heart),” a brief break from Styvers’ spirited repartee with an electrifying quartet of background singers. She invokes samba on “You Can Fly Me to the Moon” and drifts into shadowy psychedelia during “Gather the Grain,” a hymn for independence inside a close relationship. “You be you, and I’ll be me,” she sings, as if nodding to Murphy, loosening his grip. “We’ll gather the grain as we reap.” Chrysalis issued The Colorado Kid in Europe, but Warner Brothers never bothered to release it stateside. Perhaps they assumed that Carole King’s Tapestry, which Styvers had absorbed while writing, made it redundant, flattening the experience of piano-playing women to one. The month of The Colorado Kid’s release, King played for 100,000 people in Central Park; it’s hard to imagine that Styvers’ music couldn’t have found some fans within that throng.

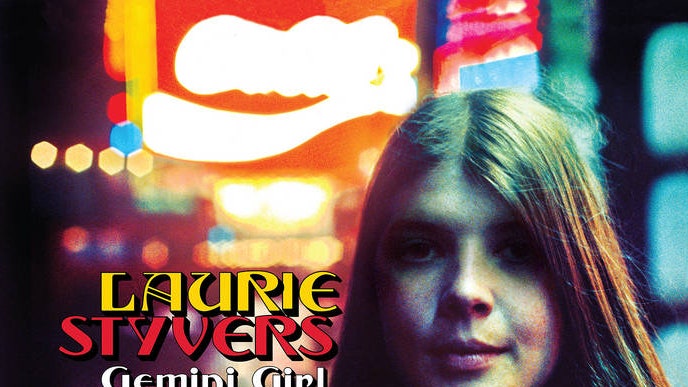

In the reissue world, the temptations to aggrandize tragedy and rewrite history loom large. Does what’s been newly salvaged stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the songs we already know, the singers we already cherish? For Styvers and Gemini Girl, the answer is no. She was a fan and acolyte of King and Joni Mitchell, but her own records, however interesting and winning, lacked the singular vision of those influences. She wrote at least a half-dozen stellar songs that have now been retrieved from history’s dustbin, but they were very much part of her era’s singer-songwriter tide. Spilt Milk deserved better than “rightfully obscure,” but, as reissues often reiterate, such is the music industry’s churn-and-burn cycle.

By most reports, especially those of Gemini Girl’s liner notes, Styvers took it in stride. She did not spend the next quarter-century pining for what might have been; she settled in Texas, rescued animals, and cared for dogs with her dad. “We’re gonna find a cabin/And throw the rest away,” she sang at the end of “Heavenly Band.” At least, it seems, she found some version of that.