Among the ephemera displayed in the Joan Brown retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is the wall phone that hung in her studio, its bone-colored receiver an earth-toned abstract with cadmium yellow dabs. A blue patch at the phone’s upper right corner suggests hurried snatches at the handpiece, wide of target. Friends remember Joan Brown “covered from head to toe with paint.” While still an undergraduate she found success with abstract and figurative paintings so thick with paint that their surfaces sag and ripple, betraying how wet they remained beneath the crust—for years. She slapped on color with trowels and house-painting brushes, at times almost sculpting.

Even after she abandoned impasto for the monochrome enamel surfaces of her self-portraits—the highly personal work for which she is now better known—the sensual materiality of paint remained a constant for her, as it did for other artists, including her teachers David Park and Elmer Bischoff, associated with the Bay Area Figurative Movement. Much of this texture is lost in reproduction, along with Brown’s subtle incorporations of mixed media, such as glitter. Another pleasure in viewing the eighty works in “Joan Brown” (the show travels next to the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh) is the shock of their scale and the vibrating intensity of their candy colors.

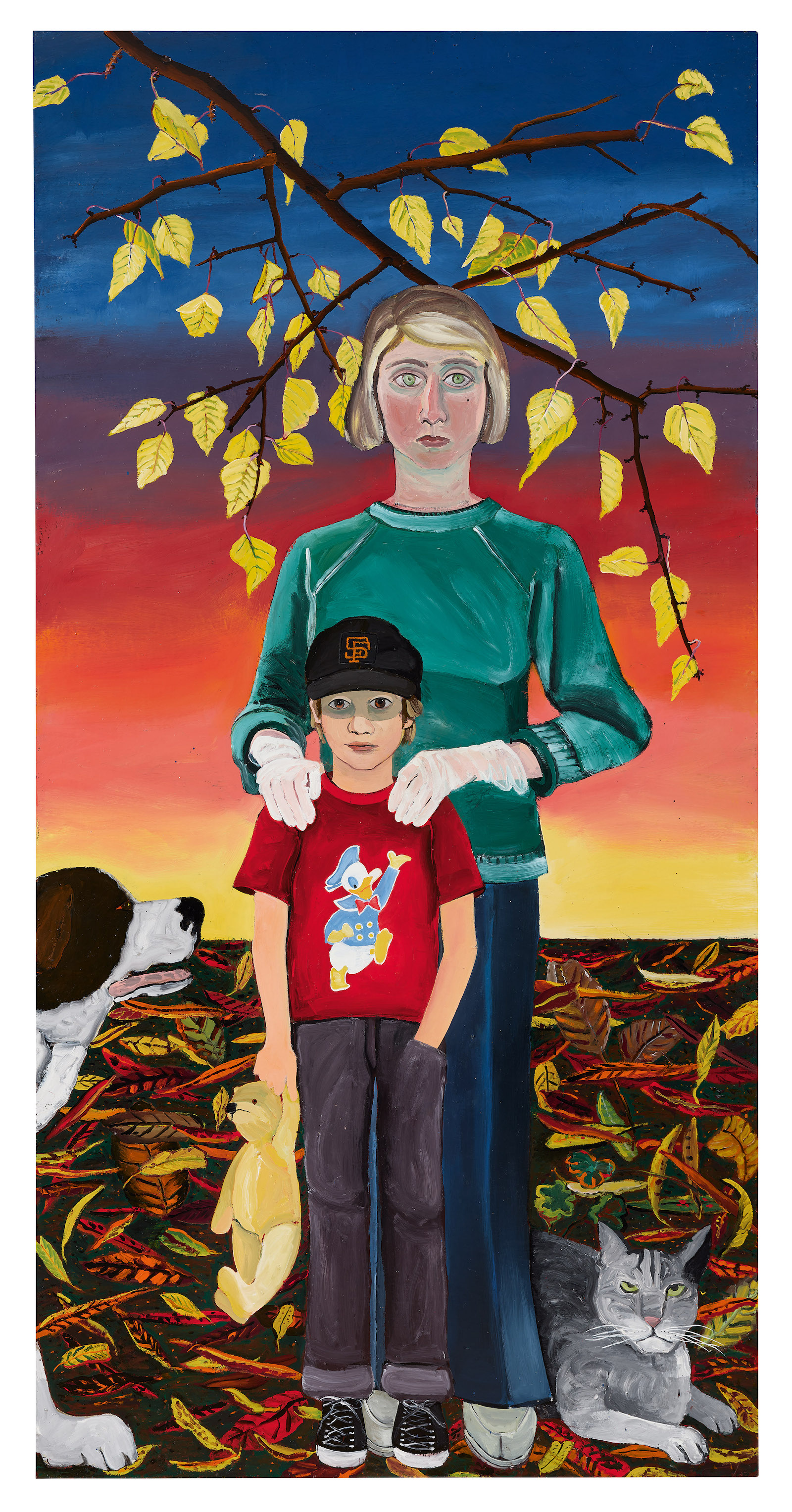

Over twenty-five years Brown portrayed herself dancing, swimming, painting, and traveling, interacting with men, pets, and her young son. She dons evening and wedding gowns, swimsuits, lingerie, and casual clothes, and appears many times as an animal or hybrid, clothed in fur or a pelt or wearing a mask. It says much for the feline inscrutability of Brown’s expression in most of these portraits that we calmly accept the substitute of a cat’s head in The Bride (1970). But in Brown’s portraits of herself at work there is little sense of costume or performance. Despite the bright colors and quick, energetic lines Brown favors, these paint-spattered figures gaze soberly from the canvas at their maker, interpretive tools for an essentially private, searching personality. “Looking in a mirror,” Brown wrote, “becoming a spectator, literally describing myself, is a very graphic way of being introspective.”

Brown’s mother, who had hoped for a teaching career instead of marriage and motherhood, was depressed and resentful; her father, a bank employee, drank. The family’s three-room Marina District apartment offered little privacy or calm. Joan, an only child, slept in the dining room with her maternal grandmother but was often woken at night by her mother’s epileptic seizures. She was shunted through Catholic girls’ schools, where she felt she learned little (outside the classroom she read constantly, particularly in ancient history and cultures). “It was dark. I mean dark in the psychological way,” she recalled of her childhood home. “All I wanted to do was grow up and get the hell out of there.”

She drew, but had no art instruction. After graduating from high school in 1955 she visited the California School of Fine Arts (later the San Francisco Art Institute) on a whim.1 Dazzled by the atmosphere of freedom and energy—students painting in the hallways and playing bongos in the courtyard—she bought a pair of arty earrings and submitted a portfolio of her pencil sketches of movie stars. She started classes that fall. Although she suffered in her drawing class and planned to drop out before summer, by the next semester she had met and begun dating Bill Brown, a figurative painter and Korean War veteran who encouraged her to take a summer course with Bischoff.

Having outgrown two of the dominant schools of his day, Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism, Bischoff (like his peers David Parks and Richard Diebenkorn) was feeling his way into figuration, a movement Willem de Kooning had spearheaded on the East Coast when he introduced his controversial Woman paintings after a successful period of nonobjective gestural abstraction. For most avant-garde midcentury artists and critics in the US, representation was hopelessly passé. De Kooning’s return to figuration prompted a disgusted outburst from Clement Greenberg, the apostle of the New York School: “In today’s world, it’s impossible to paint a face.” Bischoff urged his students to work intuitively and spontaneously—in short, like Abstract Expressionists—but to notice the ordinary objects around them.

Convinced she had “no talent,” Brown threw herself nevertheless into a series of exuberant paintings. She discovered she preferred large canvases. “I paint the size I do because I feel like a participant,” she later said, “like I can step into the pictures. When I paint small…I’m always a spectator.” She married Brown in August 1956 and the next year won second place and fifty dollars in a local juried show in which her teachers won honorable mentions. She soon featured in SFMoMA’s annual exhibitions of Bay Area art, as well as in the artist-run galleries in the Fillmore, among them the Six Gallery, where Allen Ginsberg first read Howl in 1955.

In 1958 she moved with Bill into an apartment next door to Jay DeFeo and her husband, Wally Hedrick, in a tenement building at 2330 Fillmore Street known as Painterland: a black and white Beat Era reel of chain-smoking, bathtub beer-drinking, and constant limit-pushing.2 As Hedrick recalled, it “vibrated with all of these mixed personalities…the poets came over a lot and there was a lot of bongo and chanting and sort of spontaneous musical drumming.” Jay and Joan grew close, and the two couples knocked a hole in the wall between their apartments. These were the years in which DeFeo was endlessly reworking her immense opus, eventually called The Rose; its deep impasto, as many as two thousand layers of mostly lead white and dark grey paint, was stiffened with wooden dowels.3 As she carved into its surface, DeFeo would save slices of The Rose to mount on black velvet and give as birthday gifts.

When George Staempfli, David Park’s New York dealer, came to see DeFeo’s work in 1959 at Park’s suggestion, she took him through the wall to see Joan’s paintings as well. He immediately bought two canvases. The next year he signed her, supplying a monthly stipend of three hundred dollars. She was the youngest artist in the Whitney’s 1960 Young America exhibition (and one of five women out of thirty-six artists included). Her first New York solo show, in 1961, featured her mysterious semiabstract Thing paintings, blurring figure and ground. By then she had already sold Thanksgiving Turkey (1959), a patchy but decisive abstract, to the Museum of Modern Art. She was twenty-two. Hedrick later remarked that Joan Brown was the only artist he knew who had money; her success “seemed like a fairytale.” San Francisco had no serious market for art, just a few galleries selling “clowns and landscape paintings,” as the sculptor Manuel Neri put it: “if you were making money then there was something kinda wrong with your work.”4

After Brown’s marriage broke down she moved in with Neri, a graduate student at CSFA and the director of Six Gallery. They shared a studio close to the Embarcadero and a volatile, mutually influential relationship. Brown modeled her slight, narrow-hipped body for sculptures like Joan Brown Seated (1959/cast 1963), shaping Neri’s conception of the ideal female form.5 Working beside him pulled the female figure to the center of Brown’s canvases. They traveled to Europe in 1961 for a four-month art tour that “knocked me out,” as Brown recalled, including a Rembrandt exhibition in London and Goya and Velázquez at the Prado. Her figuration over the next two years shows a profound response to the Old Masters, echoing and borrowing from their paintings as well as paying direct homage. One of these paintings, Flora, was chosen for the cover of Artforum in July 1963. Her increasingly dramatic use of color—often in bright blocks that accentuate but fail to define body parts (the cobalt triangle on the chest of the figure in Girl Sitting)—owes more to Neri’s influence and to the push–pull between abstraction and figuration.

They married in 1962, and Brown gave birth to their son that summer. Noel Elmer Neri was the inspiration for a series of painterly semiautobiographical domestic interiors in warm roses, reds, and yellows—the paint still far too thick for fine detail—along with whimsical still lifes of cookie trays. The grid emerges, along with the checkerboard, anticipating the tile strips and the carpet-like borders of her later work, one reason Brown is sometimes connected with the Pattern and Decoration movement.

Brown’s stylistic development can be roughly periodized into her four marriages, or into her three main eras of work: lush semiabstraction; flat, diary-like self-portraits; and symbolically rich late works drawing on ancient religions. And her entire career can be cleaved into before and after 1964, when on the verge of achieving a national reputation she chose to stop showing her work and experiment instead. She had lost interest in the impasto that collectors wanted from her; it was “getting monotonous,” she recalled. Stunned, Staempfli released her. Brown and Neri divorced two years later, but Brown’s stepdaughter Ruby Neri remembers how much her father admired Brown’s indifference to the art market: “Joan doesn’t give a damn.”

Brown had warned Staempfli earlier that her motives were not commercial: “I would never sacrifice what I want to do and what is necessary for me to do, even if I have to collect garbage for a living.” Her decision was not unprecedented in her circle. DeFeo had withdrawn from the art world in 1963 and stopped making art entirely for four years after her eviction from Painterland forced her, heartbroken, to “complete” The Rose in 1965.6 Both women continued to teach. This was one of the few areas in which Brown conceded she had been held back as a woman: she had to piece together a living from small teaching gigs, often working nights and weekends, since college art departments preferred to hire male artists. After securing an assistant professorship at Berkeley in 1974, she came to regard teaching as a vocation equal to painting.

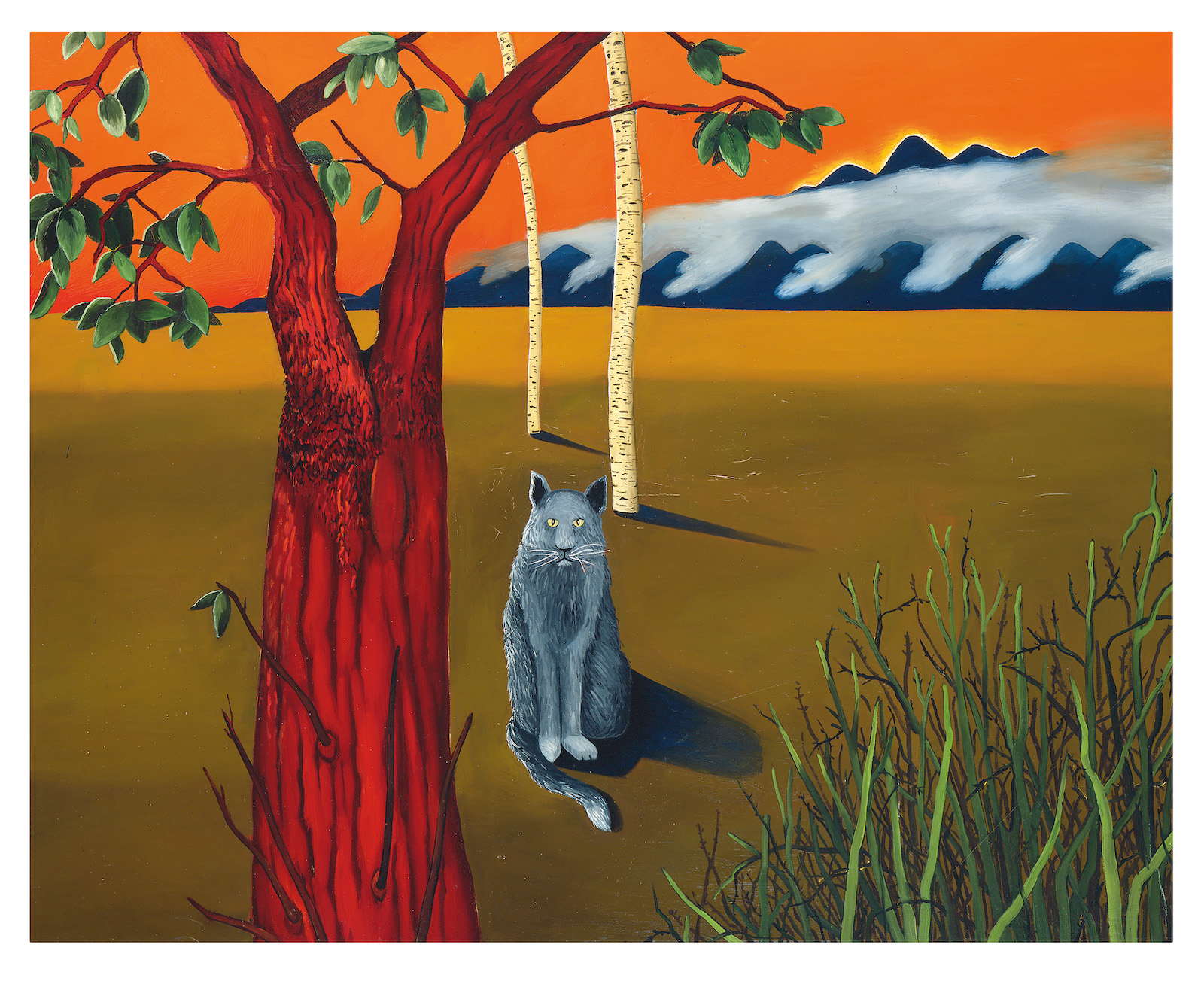

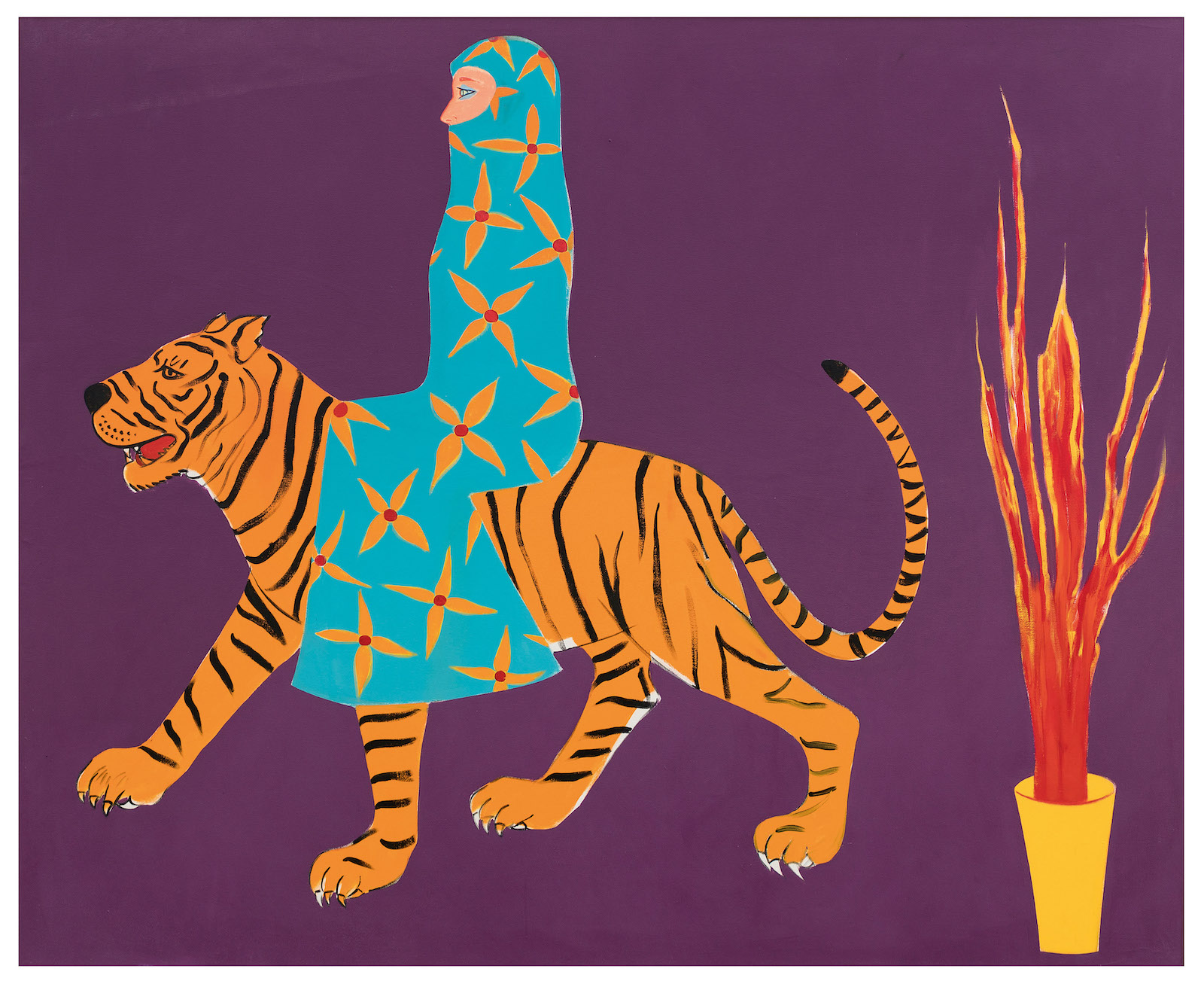

In the studio she began from scratch, trying to achieve control without losing vitality. Skeptical responses to some small still lifes didn’t faze her: “I was turned on, I was excited, I didn’t care.” She painted a series of dreamlike animal-themed works in the late 1960s, the result of daily life drawing at the zoo and Golden Gate Park and intense identification with specific animals: the cat is to Joan Brown as the bull is to Picasso. Although these “fantasy” works, as Brown termed them, were panned when she exhibited them locally, she came to regard them as the first of her more spiritual paintings, connected with her longstanding interest in ancient symbology. They led her back to the human form, but they also prefigure the animals and cat-human hybrids throughout her later work, explorations of our dual nature: “It was always very poignant, that play between half animal and half human.” The most spectacular of these hybrids, a diptych called The Bather #5 (1982), with its sinuous odalisque foregrounded against a tiled fountain, is too large for the exhibition and hangs elsewhere at SFMoMA. The figure’s placid, Ingres-inspired head rests sphinx-like on a tiger-striped body, every element of which, except the tail, merges the human with the animal. The dealer George Adams remembers Toby, one of Brown’s cats, observing their conversation during a studio visit, turning his head between Adams and Brown as they spoke. When he pointed this out, she replied nonchalantly: “He knows exactly what we’re talking about.”

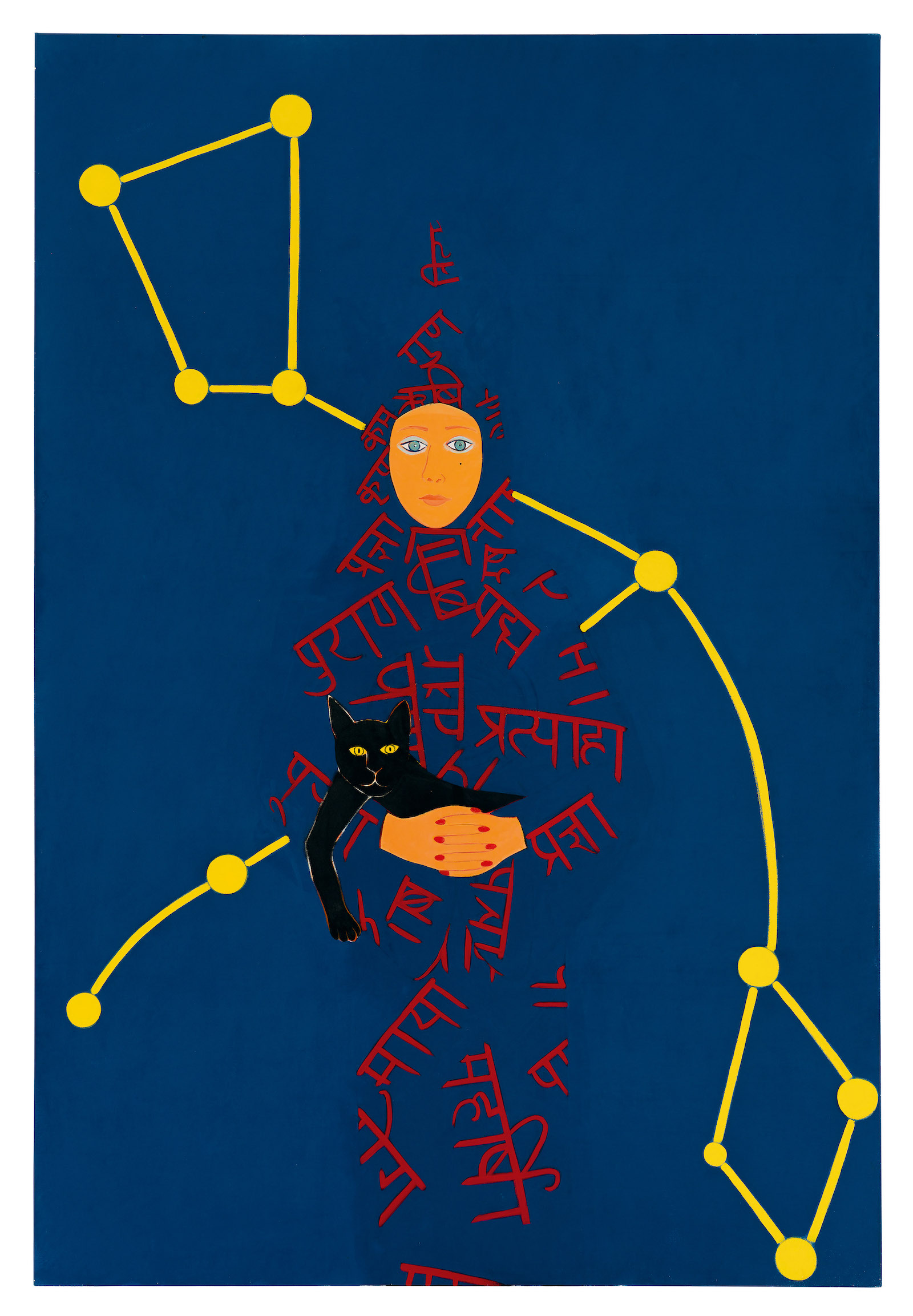

With her third husband, Gordon Cook, a longtime friend who taught printmaking at the San Francisco Art Institute, Brown moved to a house along the Sacramento Delta. While there, she picked up a can of enamel house paint and finally achieved the flatness and color saturation she had been working toward since abandoning the troweled paintings. In a rush, the monumental self-portraits began to appear—more than eighty over the next two decades—ceaselessly processing and documenting her ideas, major life events, and relationships, often against backgrounds that included Bay Area landmarks or the downtown San Francisco skyline. These were fast, fluid paintings, although one of her most arresting from this period, Portrait of a Girl (1971), a self-portrait as a child against a magnificent Chinese dragon mural, shows that she could slow down to incorporate semi-legible symbols (and ideograms, in this case) from cultures that inspired her. The Mayan frieze behind the animals in The Golden Age: The Tapir + The Jaguar (1985) is another example, as is The End of the Affair (1976), not included in this show, a narrative work divided into two scenes. The left is of a solitary male figure in black, seen from behind; the rosier right half shows a couple sitting on a bed together, the male figure covered completely with hieroglyphs, an assortment of which surround his female partner on the bed like collage scraps. Intended as homages, these cultural borrowings are, Marci Kwon argues in the catalog, “reduced to totems of difference and become accessories to the story of Brown’s life.”

Cook introduced Brown to open-water swimming in the frigid San Francisco Bay, which led to a new series painted with even more economy, inspired by her coach Charlie Sava’s critique of her swimming strokes. As a member of the all-male Dolphin Club at Aquatic Park Cove, Cook could enter the water from the clubhouse, but women had to hide their clothes and keys and swim from the beach, then build small fires afterward to warm themselves. In 1974 Brown spearheaded a successful class action lawsuit against the Dolphin Club and two other all-male water clubs at Aquatic Park.

The most moving of Brown’s swim paintings record the 1975 Alcatraz swim, an annual women’s event in which she almost drowned after a freighter passed among the swimmers. Brown and eight other women had to be hauled from the water into rescue boats. In each of the three numbered works that followed, Brown contained the emergency to a painting within a painting. Stoic, solitary female figures in nautical dresses sit or stand in simple interiors, their backs to a scene of chaos, choppy water, and near-death. Rich carpets under their feet reinforce the pleasures of terra firma. Brown continued to strip back volume and extraneous detail, so that in these paintings and the joyful Dancers series (1972–1976) her figures are reduced to deft brush drawings colored in with uniform washes or left as ghostly unfilled outlines.

These were the works that began to reengage critics and dealers, and during the 1970s they showed at SFMoMA, the Whitney, and Berkeley. (Berkeley and the Oakland Museum of California also mounted her largest retrospective to date, “Transformation: The Art of Joan Brown,” in 1998.) After a trip to Italy in 1976, the Dancers transitioned into a quieter and more personal series exploring romance—including one of Brown’s few images of herself smiling, in The Dinner Date #2 (1973). But this was not a resting place, either. “Joan being Joan,” as George Adams recalled, “she was only interested in what she was doing next.”

Cook and Brown divorced in 1976, not long after Brown took Noel on a long European tour funded by an NEA Visual Artists’ Fellowship. The next year a Guggenheim Fellowship took her to Egypt. She traveled the world—Mexico, Africa, China, India—often returning to sacred sites or those of archaeological importance. She pored over theosophical texts, the popular Seth books by Jane Roberts, and works like Fritjof Capra’s The Tao of Physics (1975) that drew parallels between Western science and Eastern mysticism. At this point her studies of myth and religion found an echo in the New Age movement—a synthesis of various Eastern beliefs with the West Coast antiestablishment ethos of the late 1950s and 1960s.

What Adams calls “travel” is code for the unsettling metaphysical subject matter of Brown’s later work, the temple settings and religious imagery through which she advanced her growing conviction that ancient belief systems had an underlying unity. She saw this unity expressed formally as well, remarking on the similarities in architectural styles (the ziggurat, the pyramids) and the use of line and space in two-dimensional works across disparate cultures. Her Egypt-inspired paintings were dismissed as “vapid” and “corny,” but she had moved beyond aesthetic evaluations; her works were no longer about that.

In 1979 she met Mike Hebel, a city police officer and fellow seeker, at the Ananda Community House in San Francisco. They married the next year in a Hindu ceremony at SFMoMA. Joan wore a sari, as her student Bob Brokl recalled, and “was borne in on a litter. She picked the most attractive male art students.” After their first trip to India together Brown and Hebel became devotees of the guru Sathya Sai Baba. From this point on Brown held a mystical worldview, open to signs and wonders. On return visits to Sai Baba’s complex in Puttaparthi, she hung on her brief moments of contact with him. She introduced Jay DeFeo to his teachings and tried to bring her to India to meet him. She came to believe that Sai Baba directed all her artistic endeavors and took on several public commissions, including three surviving tiled obelisks in San Francisco, intended to democratize her work and spread her guru’s humanitarian message. These site-specific works combine animal imagery with local elements and subtle religious symbolism, as if to compare the spiritual ease of the animal world with the turmoil and material strivings of humanity. When Brown was finally granted an audience with Sai Baba in 1988, all she asked was his help in healing DeFeo, who had cancer.

In September 1990 a call came into the art department at Berkeley with the news that Brown had died in India. “We were devastated,” her colleague Katherine Sherwood remembers, until “Joan called.” No one ever found out who had reported her death. A month later, Brown and her two American assistants were crushed by a concrete turret that fell into the courtyard of the Eternal Heritage Museum in Puttaparthi while they were installing a thirteen-foot obelisk, her gift to Sai Baba. She was fifty-two. Some years earlier Brown was asked what kept her painting. Her reply would have made fitting last words: “To just keep growing and changing, and just keep letting go, letting go, letting go of any kind of boundaries or rules and regulations that I or anyone sets up. But what I mainly want is to be surprised. The joyousness of that surprise. Going past what you know.”