The Student of Prague, made in Germany in 1913, may well have been the very first horror movie ever made. Even if it wasn’t the first it must surely be the oldest horror movie still in existence.

Another silent version of this story was made in Germany in 1926. I haven’t watched that one yet but I intend to do so in the next couple of days.

When viewing a movie from such a very early period in cinema history one is inclined to make allowances. Such early movies usually suffered from very static camera setups and can be inclined to be a bit creaky. In this case however no such allowances need to be made. This is a very fine movie and it compares quite favourably with movies of the later silent era.

Of course it is a silent film and silent films are very very different from sound films. Making movies without dialogue required a particular technique, the use of a purely visual language. Silent films do take a bit of getting used to. It’s worth the effort though, and this is especially so if you’re a fan of horror movies since the silent era produced some of the greatest horror movies ever made.

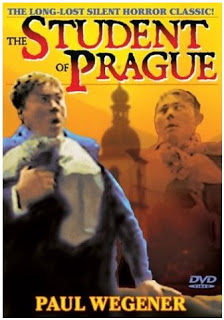

The Student of Prague was inspired partly by Edgar Allan Poe’s short story William Wilson although it also draws upon the story of Faust. The movie was written by Hanns Heinz Ewers, a writer who produced a number of bona fide classic horror stories. Paul Wegener, an important figure in the early German film industry, produced and starred in the movie and shared directing credit with Stellan Rye, another important early German film-maker who unfortunately was killed in the First World War.

Balduin (Paul Wegener) is renowned as the finest swordsman and the wildest student in Prague. The setting would appear to be the early or mid-19th century. Balduin is facing financial ruin when he encounters a rather mysterious, slightly sinister and somewhat eccentric-appearing character named Scapinelli (John Gottowt). Unbeknownst to Balduin Scapinelli is a sorcerer and, as we later discover, an agent of Satan. Scapinelli offers Balduin a deal. He will give the penniless student a hundred thousand gold pieces if Balduin will allow him to take one item from his room. The item Scapinelli selects is Balduin’s reflection.

This transaction is a little disturbing but Balduin is glad of the money. He is in love with the Countess Margit Schwarzenberg. She is betrothed to a cousin, the Baron Waldis-Schwarzenberg. As you might expect this situation can have only one outcome – Balduin and the Baron will fight a duel. The countess’s father begs Balduin not to kill the Baron, the Baron being the last of his line. Balduin agrees but the Baron is killed anyway. Not by Balduin, but by Balduin’s reflection.

His reflection has taken on a life of its own and it has been dogging the young student for some time. It is his double, his doppelganger, but it represents the darker side of Balduin’s nature. Balduin, not surprisingly, becomes increasingly agitated and depressed. He tries to distract himself with dancing, drinking and gaming but it is of course no use. His reflection continues to dog his footsteps and it seems that the future for Balduin must hold either madness or destruction.

The movie makes use of surprisingly successful split-screen techniques to allow both Balduin and his evil double to be onscreen at the same time.

The technique of using close-ups and breaking up a scene by cutting to different angles had not yet been developed, and camera setups were static and were confined almost entirely to medium-long shots. This tended to make things rather boring visually. Wegener and Rye deal with these problems very effectively. They do everything they possibly can to maintain the visual interest of the viewer. They use deep compositions with action in both the foreground and the background, they shoot through gateways and doorways, they have actors entering scenes from doors in the background. The end result is that the film does not feel static or dull. In fact, quite the reverse, it’s visually quite impressive.

Expressionism would not appear in German cinema for several years yet but it is clear that German film-makers were already intensely aware of the importance of the visual impact of movies. They were already aware that movies should not look like filmed plays.

This movie is certainly not studio-bound. There is quite a lot of what is clearly location shooting and this again helps to make the movie feel dynamic and fast-paced.

The Alpha Video release appears to be the only DVD release of this movie currently available. With a 41-minute running time the print used was obviously incomplete. A much longer restored version apparently exists but I have been unable to find it on DVD. As you would expect from Alpha the picture quality is pretty rough. I have no idea what the score is like since I find it impossible to endure the scores customarily used on DVD releases of silent movies these days. I simply turn the volume down to zero and concentrate on the images.

The Student of Prague obviously has immense historical interest but it’s also an entertaining and effective horror movie and it’s most certainly worth seeing.

SOURCE: Cult Movie Reviews – Read entire story here.